Chen Guangbiao: Paper tiger

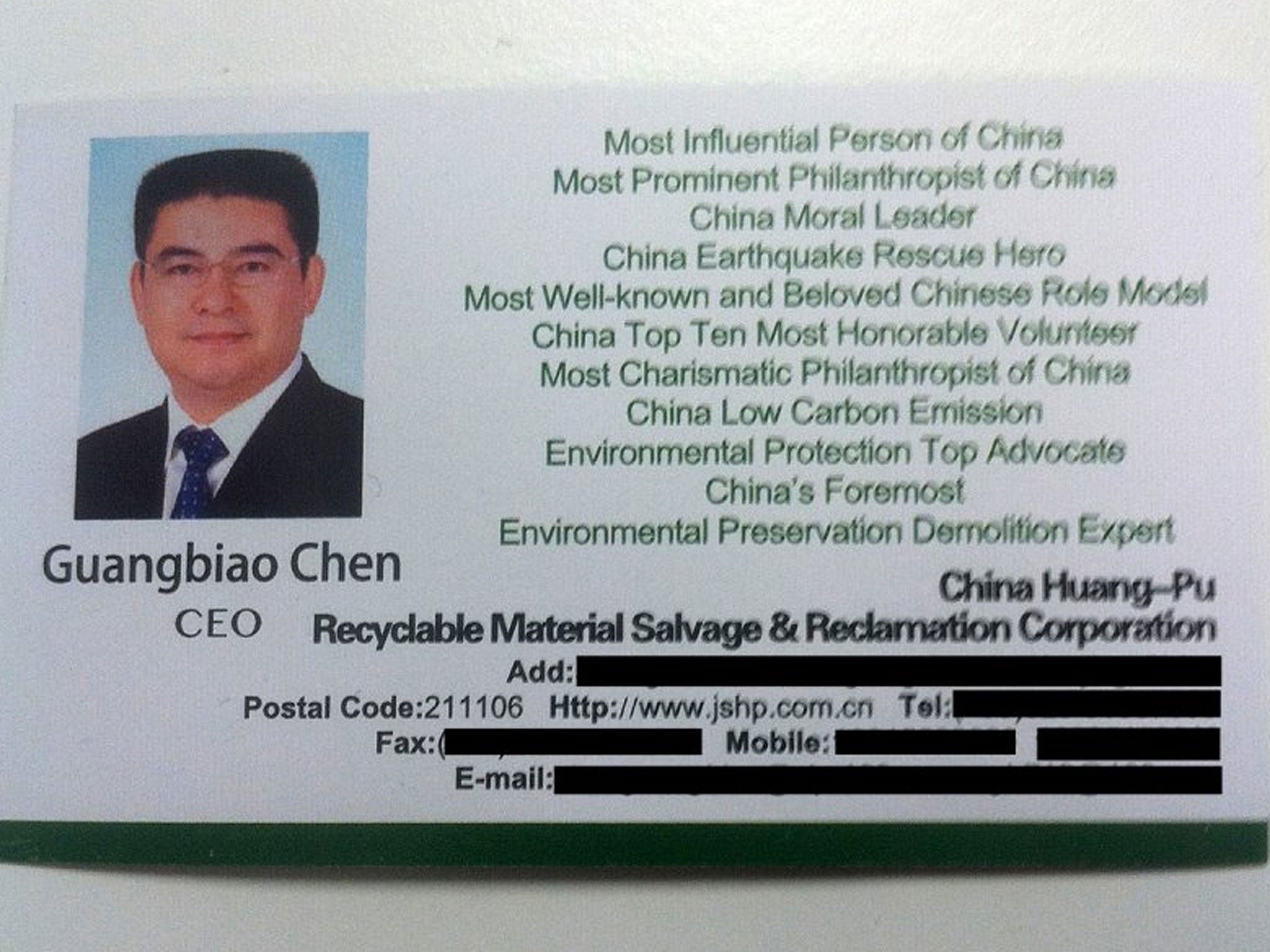

Chinese entrepreneur Chen Guangbiao's bid to invest $1bn in The New York Times didn't get him through the door – despite having the business card to end all business cards.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Every smart Westerner operating in China knows the local business-card etiquette. The small rectangle of paper exchanged at meetings must be gripped with two hands in order to demonstrate mutual respect. The card must not be casually slipped into a pocket or handbag, but held aloft and admired.

Chen Guangbiao's business card is impossible not to admire – if only for its stunning braggadocio. It describes the boss of Jiangsu Huangpu Renewable Resources as the "Most Influential Person Of China", "China Moral Leader and "Most Well-known and Beloved Chinese Role Model".

Alas, none of these spectacular attributes was enough to get Chen through the door of The New York Times. The 42-year-old recycling magnate had expressed his desire to make a £1bn (£608m) investment in the American journalistic institution. But his response from "the Grey Lady", Chen disclosed this week, was a brief memo declining even a meeting.

What does a wealthy Chinese businessman want with The New York Times? Philanthropy, says Chen. He claimed this week that he desired to "report ways rich people can help the poor". Giving certainly seems to be high on Chen's list of priorities.

He came to public prominence in China in the wake of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, when he donated the use of scores of his company's bulldozers to assist the Chinese state's rescue efforts. The then Premier, Wen Jiabao, described Chen as a "representative of the consciousness" of private entrepreneurs.

Like a Chinese Warren Buffett, the businessman says he wants to donate all his wealth to good causes before he dies.

But Chen also wrote last year of his desire to improve America's understanding of China. Cynics might say that that was a more accurate explanation of The New York Times bid. The paper ran an investigation into the "hidden £2.7bn fortune" of Wen Jiabao in 2012. The exposé went down like a cup of rancid tea with Beijing. Could Chen's bid have been a useful way for him to ingratiate himself with the Beijing regime in order to benefit his Chinese business interests?

That would not be out of character. Last year, Chen took out an advertisement in the same newspaper trumpeting China's claims to the islands in the East China Sea at the centre of the territorial dispute between Beijing and Tokyo.

Another stunt in 2011 was a trip to Taiwan, which Beijing regards as a renegade province, to hand out money to the poor and to lobby for the construction of a bridge to the mainland. The soi-disant "flashy philanthropist", who owns at least one lime-green suit, has a special knack of pushing the interests of the Beijing authorities.

Despite the hoopla surrounding the bid, which briefly pushed up The New York Times' share price, it was always unlikely to go anywhere. The newspaper's controlling shareholders, the Och-Salzberger family, said that it was not looking to sell. And there is also a question mark over whether Chen's pockets would have been deep enough anyway.

Though he is on Forbes' list of China's top 400 wealthiest individuals, he's well down the table. China is churning out newly minted dollar billionaires as the economy registers growth rates that Western countries can only dream about. At No 1 is Wang Jianlin, the property magnate, with a staggering $14.1bn net worth. Jack Ma, the online commerce supremo, has $7.1bn. That makes Chen's estimated $800m fortune look rather modest.

Still, here is a man who also lays claim to being "Most Charismatic Philanthropist of China", "China Earthquake Rescue Hero" and "China's Foremost Environmental Preservation Demolition Expert". With such a jaw- dropping business card, who would bet against the world hearing from Chen again?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments