Built to last: the Minecraft model

Minecraft is the most successful game since Angry Birds, but will it retain its minimal merchandising strategy once it’s in the hands of Microsoft?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Minecraft just might be the most popular online paid-for computer game in the world.

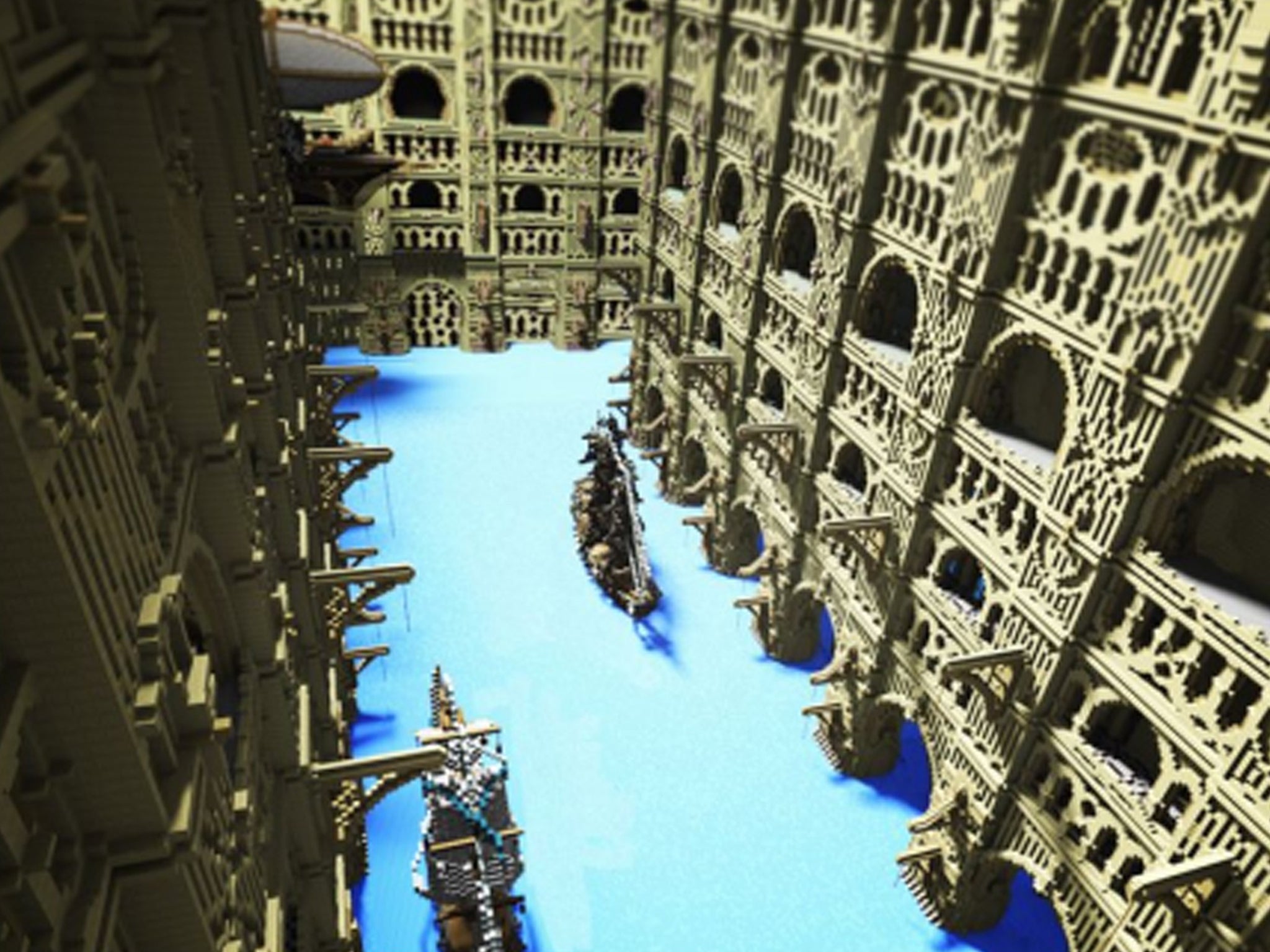

It is certainly among the most profitable. The game, which lets users construct their own highly detailed worlds of buildings, people and animals made out of chunky 3D blocks, has been a hit with children, as many parents can testify.

Part of Minecraft’s appeal is that the game is educational and cerebral, encouraging spatial awareness and planning skills, particularly in those who might have problems with dyslexia or dyspraxia. Since launching in 2009, Minecraft has won 100 million registered users, of whom about 60 million use a paid version.

The sheer scale of its paying audience – the game costs £17.95 to buy online – has defied conventional wisdom that in the smartphone era a successful game needs to be free. For example, only a small proportion of players pay for a premium version of King Digital’s smash app Candy Crush Saga.

Minecraft is different, as Mojang, the Swedish company behind the game, is eager to stress. A large subscriber base and reported annual revenues of $290m (£180m) have given Mojang the freedom to focus on refining the game and developing new ideas, while turning down countless offers for merchandising and advertising tie-ups.

But following Markus Persson’s decision last month to sell his creation to Microsoft for $2.5bn, and leave Mojang to pursue new projects, some wonder whether the Swedish start-up can maintain this purist approach – especially as it is exploring more merchandising opportunities.

Minecraft books have topped the best-seller lists, Minecraft-branded Lego toys are hitting the shelves, and a film with Warner Bros, made by the same team behind the acclaimed Lego Movie, is in the planning. And at Brand Licensing Europe 2014, one of the world’s biggest merchandising and licensing fairs, which took place at London’s Olympia this week, a range of Minecraft-branded T-shirts, plush toys and baby clothes were on display for trade buyers.

However, Mojang’s chief operating officer, Vu Bui, is adamant the company is staying true to its roots. “We make merchandising that is cool and people will enjoy – not to make money,” he declares, pointing out that the company has rejected most merchandising approaches amid all the Minecraft hype. “For us, it’s really difficult to find things we’d be interested in, because of the noise. We’re saying no to nearly everyone.”

One example of a merchandising deal that Mojang has turned down is providing Minefield-branded birthday party supplies and cakes. “What we’re interested in is families coming together and creating their own Minecraft parties – that’s what we love,” Mr Bui says.

He won’t disclose what proportion of Mojang’s revenues comes from merchandising, and goes so far as to claim the company doesn’t even calculate the breakdown for internal purposes. But he suggests it is a small part of turnover – far below the 47 per cent of sales that Angry Birds maker Rovio generates from merchandising and consumer products. The Minecraft approach is that “merchandising does not supplement the game – it is to support the game”, he says.

Part of the reason that Minecraft is so revered is because Mr Persson was careful not to over-expose the brand and to focus on the gaming experience. At the same time, Mojang didn’t try enforce its copyright by banning fans from making videos using game footage. Now YouTube carries so many Minecraft videos and commentary from fans that the number is said to rival all the cute animal videos combined. “We beat cats about a year and a half ago,” jokes Mr Bui.

But there is a serious point. “We haven’t been money-driven,” he says. “Our focus has been on building the best brand we can.”

It is easy to claim not to be money-driven when Minecraft rakes in so much revenue. “We’re pretty lucky,” concedes Mr Bui, an American who began working for Mojang as a contractor three years ago and joined a year later. “As we’re not driven by demands from above to meet certain goals, that gives us that ability to be creative and to be very picky. But even if we didn’t have the luxury about the need to make money, I’m not sure we’d change. It’s the way we want to do it anyway.”

That was a point he made in his speech at BLE 2014, as he explained why Mojang would continue to strike few merchandising deals. At present, Mojang has only about eight licensees worldwide.

The company, which employs just 36 people, plans to keep its focus on making games. “We are a games studio – we are not a media company,” says Mr Bui. “If you put too much emphasis on side projects, it will dilute it.”

He didn’t mention other companies by name, but Angry Birds maker Rovio and Moshi Monsters company Mind Candy both grew quickly, focused heavily on merchandising and licensing, but have since seen growth falter.

As well as apparently not calculating merchandising sales as a proportion of the business, Mr Bui says Mojang collects little data on its users – apart from payment details – because the company puts “concerns over privacy above the business”. So although there is anecdotal evidence that Minecraft is increasingly popular with girls as well as boys, the company does not compile that data or track users’ emails.

Developing new games is the big challenge. About 27 million of Minecraft’s paying users are on mobile devices, 17 million on desktops and laptops, and 16 million on gaming consoles such as Microsoft’s Xbox. However, Mr Bui, who confesses that he doesn’t play Minecraft much himself, says gaming is not moving inexorably on to phones and tablets.

Mr Bui won’t discuss what plans Microsoft might have once the acquisition completes, probably by the end of the year, but he is hoping Mojang’s purist approach can maintain the halo effect around Minecraft. “Everything dies off eventually – no matter what it is,” he says. “The way we see it, we are working this way to preserve the longevity of the brand.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments