‘Each mile is not a carefree mile’: What it’s like to be a black runner in America

Going for a run is supposed to be a way to unwind, to relax and enjoy. But for many black runners in America, this is not the case. Kurt Streeter provides six accounts of what it is really like to be a black runner

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Our jog is just beginning when my young son asks the question. “Dad, today can we go through my favourite neighbourhood?” During the pandemic, we’ve made a habit of running together in the early evening. We course down the middle of calm streets, exhausting ourselves as best we can. It’s become our way to bond.

But now my jaw clenches. The neighbourhood that has become his favourite route? I have to think fast. What should I say to him about how that place makes me feel? How would I ever tell him about the killing of a black jogger in a corner of the country far from ours. When will be the right time to explain to a nine-year-old the wariness that comes every time I lace my clunky green sneakers and pad through the streets in our almost entirely white Seattle community?

I’m not a great runner; I’m a 6ft-2, 220-pound plodder who tends to wilt at mile four. But I get out there as much as I can, to ease the stress and to feel free.

And there lies the complication. Like many black runners, the very act of doing one of the things we love most in life comes with searing existential stress and constraint. I’ve been putting in hard, slogging miles since 2005, as I processed the fact my father was dying. Out there on city streets, visible and vulnerable, I have never jogged without the spectre of race. The way I look shadows my every stride.

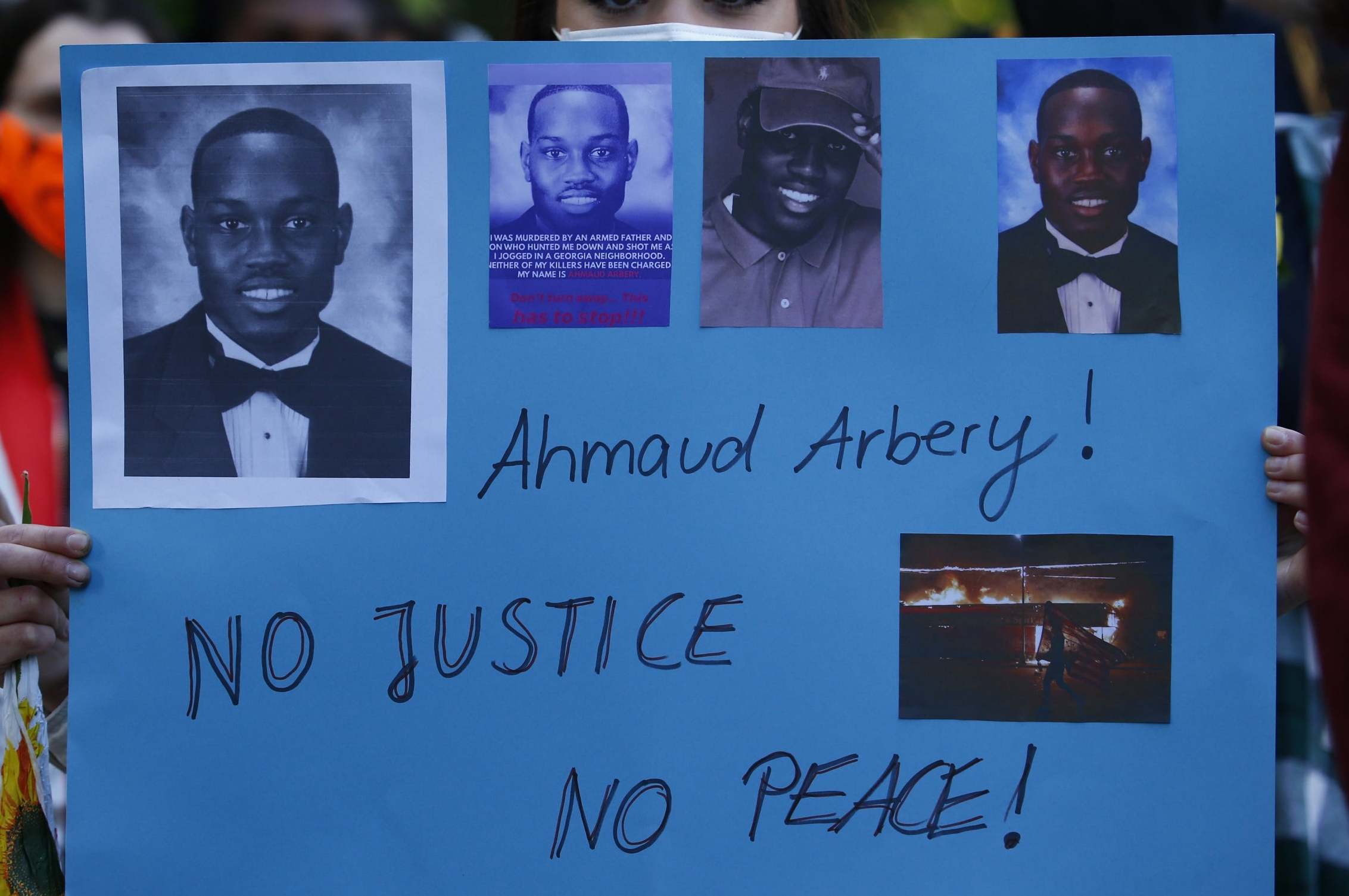

Sometimes it’s in the forefront of my mind – gutting, angry, mournful – as in the days after Ahmaud Arbery was chased and fatally shot. Sometimes it’s in the far corners, background noise, but still inescapable. I run to feel joy. To sense my 53-year-old legs churning and the wind pushing across my face, to think about stories I’m writing, to ponder ways to be a better husband and father. But I do all of this with a measure of vigilance.

On my runs – which, pandemic aside, are usually solo – my mind hums with questions. Would it be better if I lived somewhere else? Why is the truck behind me on this street going so slowly? If I need to get away, which way would I sprint? If I need to turn and fight, would I kick, tackle or punch? Why did that officer circle back around and pass me twice?

I live a 15-minute drive from downtown, amid blocks of tidy homes, old and new. On my sweat-soaked outings I’ll see a unique porch, a curving roof, a well-preserved Tudor. My father was an architect, so it’s in my bones to be curious about the way houses are designed. That only sparks more questions: Should I stop? If I do, how close should I get? How long should I linger? What will the neighbours think?

Then there’s my iPhone. To some, snapping off a few frames with a cellphone camera makes me look like a prowler. Cellphones can also be mistaken for guns. Not a chance I’m pulling it out.

A few years ago, on a run about 10 minutes from my house, I stopped briefly in the middle of a street to tell a white homeowner how much I admired the minimalist fence that led up her stairs. She was in her yard. I was 20 feet away, sure to smile, and to not move any closer. I immediately saw worry in her eyes. She backed up a few steps. Someone bolted out from her front door, sceptical and scowling, as if I were an attacker.

I turned back to pounding the pavement, imagining what the reaction would have been if I were blue-eyed and blonde.

“This is my neighbourhood just as much as it is theirs,” I told myself. My family helped integrate this area and its schools, starting in the 1950s. And these days, the block where I live is a place where I feel great care. (It’s away from that block, on less familiar streets, when my radar rises.) So I gave a chagrined laugh at what had just taken place. It’s all we can do sometimes. Smile against the pain and disappointment, reminding ourselves that it’s about more than us in any one moment – it’s about a tangled and brutal 401-year history.

But this day was different. Earlier, after watching the horrific video of the killing in Georgia, I’d collapsed on our couch, tears in my eyes

That legacy is what I thought of when my son asked whether we could run through his favourite neighbourhood. It’s adjacent to ours, a bit north and a lot more upscale. One of those gilded, set-apart communities with a homeowners’ association and lawns that look like putting greens. It doesn’t seem to have any trees on the sidewalk strips, so when I run there I feel as if I am in a fishbowl. Everyone can see us. I’ve never seen another black person in that neighbourhood.

It’s a beautiful place, no doubt. My son loves it mainly for its wide, lightly travelled streets. They’re ideal for jogging, especially now. “Dad, can we go there?”

We’d been doing just that on occasion over the past few weeks. But this day was different. Earlier, after watching the horrific video of the killing in Georgia, I’d collapsed on our couch, tears in my eyes.

“Dad?”

I don’t fear that neighbourhood, at least not any more than my own. But I can’t move through it without heads turning, without drawing objectifying smiles or looks that feel like doubt. I didn’t need to feel any of that.

“We’re not going there on this run,” I said. “Some other time, I promise.”

“Why?” he replied.

“Have you ever seen any people of colour in that neighbourhood?” I asked. “It’s even more segregated than where we live. I’ll tell you more one day. Just not today.”

My son managed a comforting smile. We turned the opposite direction, making the best of every moment, every stride, me with eyes wide open, him lopping along, content and carefree. It ends up being one of the best runs we’ve ever had.

– Kurt Streeter

‘Turn down your music!’

On the surface, Los Angeles is a mostly liberal town, but white privilege runs deep. I was verbally assaulted by a white man while on a morning run. I’ve been dreading the moment I might run into him again, wondering if he will be emboldened by our encounter.

I ran around this guy and the cute, unleashed dogs he seemed to be walking. Once I passed him, he yelled after me over and over again. I had a bad feeling, so I just kept running. I felt him run up behind and then come up next to me. He had run past his dogs to catch me just to let me know that I “can’t just run up on him like that”. I silently put my earbuds back in and kept running. He tried to keep pace running alongside me, and yelled “Turn down your music!” I told him to just stay away from me and he yelled, “You stay the [expletive] away from me.” I told myself just keep running, so I did. He took out his phone and started taking video of me running while his dogs ran after us barking, probably thinking we were playing.

I haven’t stopped running on that trail, and I don’t plan to. The only thing that’s changed is I now run with pepper spray.

Ito Aghayere, Los Angeles

‘I’ve got mace’

In 2017, my wife and I moved to suburban Columbus, Ohio. About two weeks after we moved, I was running in the morning down neighbouring streets, trying to establish new routes. A woman who was leaving her home and getting into a car in her driveway did not notice me until I was nearing her driveway. I keep keys in my pocket so I can be heard.

When the woman finally noticed me, she let out a gasp and said, “I’ve got mace.” I kept my pace and continued to run in a straight path. By the time I was at her driveway she was reaching inside her bag and screaming, “I’ll mace you.” I passed her without changing my speed or deviating from the run. Then I just went home.

For the past week or so, I can’t help but think of how close I was to being assaulted on the same block where white men are freely able to walk around carrying weapons.

Mario T Calhoun, Bexley, Ohio

‘I create a “what if” checklist’

Every single time I step out my door to run alone I create a “What If” checklist. What if someone tries to run me over, what if someone pulls up next to me to yell at me, what if someone tries to pull me into a vehicle? I have a plan just in case one of those “what if” moments were to occur.

I have my phone tracker on and have all photos and videos taken on my phone automatically uploaded to three different cloud platforms. I have given some friends and family access to my tracker so they can attempt to find me just in case something were to happen. And I am conscious of what I am wearing to make me not look as if I am “suspicious” or “not doing what I shouldn’t be doing”.

I run more than 20 miles a week. And each mile is not a carefree mile. I carry the weight and burden of the fears of what may be a harmful or detrimental experience that is undocumented and unjustified.

Stephanue McGrew, Kirksville, Missouri

‘Even in my own neighbourhood, I fear’

I’m a husband, the father of four beautiful daughters and in the army, so staying in running shape is not optional for me. I live in a gated community in the birthplace of the civil rights movement, but also the cradle of the Confederacy. There isn’t a day that goes by that I run and don’t think about safety.

Even in my own neighbourhood, I fear. I think about how Trayvon Martin was in his own gated neighbourhood when he was followed and gunned down

Most of the time I try to run in my army physical fitness uniform or bright clothes and a reflective belt. I always run with my phone just in case something happens. At least my family would know what happened to me if I could pull out my phone and record it.

Even in my own neighbourhood, I fear. I think about how Trayvon Martin was in his own gated neighbourhood when he was followed and gunned down. When it starts to rain a little bit, as it did the night Trayvon was killed, I cut my run short because of what happened to him. I think, they won’t believe I’m just trying to run in the rain.

There’s a lot of trucks here with Confederate flags similar to the one that followed and killed our dear brother Ahmaud Arbery. Unfortunately, there’s so much unwanted anxiety running while black, and it’s further exacerbated with this senseless murder. We want to make it home to our families.

Marren Ellis, Montgomery, Alabama

‘Did anyone else see that?’

I’ve trained for 13 full marathons and many other race distances. I run with my very intelligent, fun, selfless and beautiful co-worker, and I feel safer. She is white. When I run with her, it’s for companionship. I adore her. I also feel safer with her around. When people do the “South Philly slide” past stop signs, they see her. They stop and apologise profusely for rolling through a stop sign. When it’s just me, I get cussed out, or, in worse situations, called a [epithet]. Those words really hurt, so I block it out. I run with music so that if it happens more often, I won’t be able to hear it because I have a music blanket for protection when my running buddy is not around.

The worst of it came as we all went into shelter in place in Pennsylvania. All of our local running groups remind us to run early or late to avoid crowds. I unfortunately listened to that advice one morning and went for a three-mile run. Halfway through, as I turned around, there was a hunter green pickup truck stopped in the middle of the road. I found it bizarre and slowed my run to a trot. As I got closer, I noticed the truck was decorated with Trump/Pence 2020 stickers, along with a Confederate flag. My stomach dropped and I felt panic run through my body as they revved their engine several times in the middle of the road. I looked for escape routes in case they tried to jump the curb to hit me. I decided to be brave and pretend they were not there.

As I passed them, they turned a corner down the street. We all peered at each other, until turning the corner broke their gaze. It was so uncomfortable and so confusing. Did anyone else see that? (No – I was alone and the streets were empty.) What just happened? What was that? I told my boyfriend about it and haven’t shared that experience with anyone else since. I now choose to run during peak hours with my BFF, with enough people around – just in case.

Jade Tuff, Philadelphia

‘I don’t want you to shoot!’

Before I step outside of the house, I run through the following set of questions: Is my beard too thick? Is it too dark outside? Am I dressed like a runner? Then, while on the run, I have to consider the following: Is my rap music too loud? Does my cap, worn backward, send the wrong message? Do I open up my stride now or wait until I get out of the neighbourhood and into the open roads so that I don’t appear to be “running away” from something or someone?

Then there is scenario-planning while running: If you see a white young woman on the same path, cross the street immediately and try not to make eye contact twice. If it’s a white older woman/man on same path, wave/nod/smile, cross street casually. If you’re running behind them and they don’t hear you, cough loudly/clear throat, cross street. If on a narrow sidewalk, always give way to walkers/bikers and step into the grass or street even though you’ve shattered your ankle twice. Turn volume down on music when passing by neighbours. Need to be able to respond should they say something so as not to be profiled as an angry black man.

I’ve been doing mental gymnastics while running since I was 16. I’m 37 now, and I’ll continue doing it for as long as I live. The truth is, I don’t really want to do any of those things, but sadly I’m too concerned with what would happen if I stopped. So at mile five, when I’m sucking wind, sweating profusely in sweltering heat with an elevated heart rate, you’ll always catch me across the street waving neurotically and smiling. Again, not because I want to, but because I don’t want you to shoot!

Benyam Tesfai, Carrollton, Texas

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

41Comments