Black lawmaker hopes highway project can right an old wrong

Tennessee state Rep. Harold Love Jr.'s father put up a fight in the 1960s against rerouting Interstate 40 because he believed it would stifle and isolate Nashville’s Black community

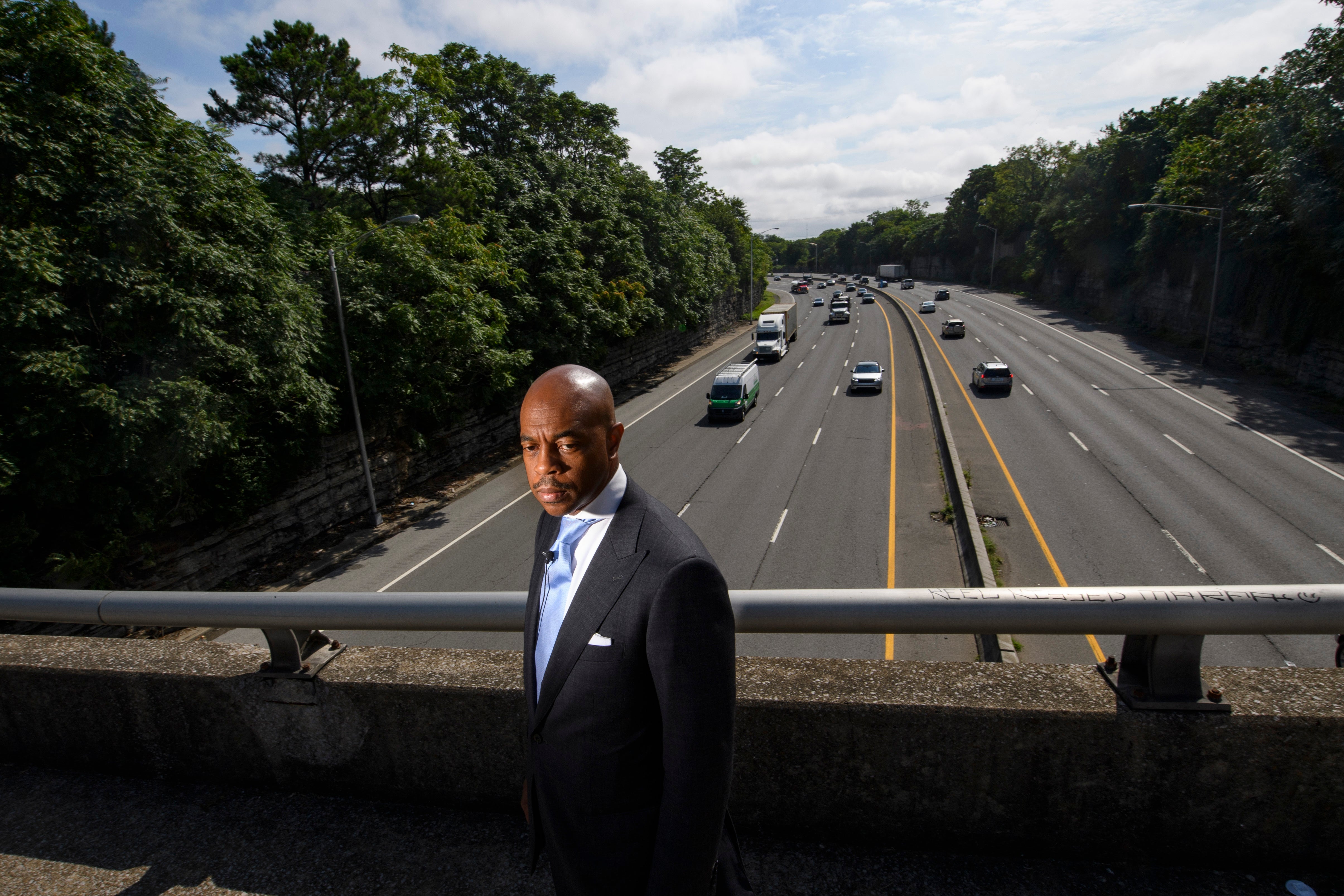

Harold Love Jr. raised his voice over the blare of traffic from the interstate above as he stood near the spot where his family's home was razed to rubble a half-century ago. Love recounted the fight his father put up in the 1960s, before he was born, to reroute the highway he was sure would stifle and isolate Nashville s Black community.

His father was right.

Decades later, Love Jr. wants to correct an old wrong. The state lawmaker is part of a group pushing to build new community space he says would reunify the city directly over Interstate 40, turning the highway stretch below into a tunnel.

Mayor John Cooper backs the $120 million, 3.4-acre (1.4-hectare) cap project. The city will spend months listening to ideas about what it should look like, cognizant of a past that saw community concerns about the highway ignored, and the booming growth of the city that challenges longtime residents’ ability to stay. Possible options include a park, community center, amphitheater, and some way to preserve the historical context about businesses that used to line Jefferson Street, the once-thriving heart of Black Nashville.

As the hum and heat of the highway enveloped the dead-end street where his family's home once stood, Love, now a Democratic state representative and pastor at a church nearby, lamented the psychological damage done by the destruction.

“If you’re born here and all you see are these structures like this that are wrought-iron fences and chain-link fences and the noise from the interstate, what you assume is, ‘I’m not valued,’ because they placed this here,” he said. “But if you could change that model and talk about how you were once valued in this neighborhood, and were trying to re-create that value by putting this (cap) here, you may change the mindset of children growing up here.”

Amid the fight for civil rights in the South, the Interstate 40 route carved up Black neighborhoods where homes and businesses stood, dividing many from the business and music district on Jefferson Street and the city center beyond, separating one of three nearby historically Black colleges.

An estimated 1,400 North Nashvillians were displaced, 100 city blocks demolished.

To this day, North Nashville residents remain disconnected, leaving amenities such as Vanderbilt University and two major hospitals accessible only by highway underpasses and bridges. The ZIP code that covers North Nashville, nearly 70% Black according to U.S. census figures, has a poverty rate more than double the city as a whole, which is 27% Black.

President Joe Biden’s proposal on infrastructure has directed attention to Black communities nationwide that were carved up to make way for highways, including the “Main Street of Black New Orleans,” Claiborne Avenue, which had a freeway built above it in the 1960s, and Miami's Overtown neighborhood, once nicknamed the “Harlem of the South.”

Andre Perry, a Brookings Institution senior fellow, said the issue largely started with housing discrimination, as New Deal benefits went more to whites than Blacks, leading to white suburbs that excluded Blacks but needed highways to reach city job centers.

“It happened so frequently and it happened in so many areas because where Black people lived was in the city core,” Perry said.

The Nashville cap project suffered a recent setback when the federal government rejected a $72 million infrastructure grant application. But Cooper has vowed to pursue other funding options as debate over infrastructure continues.

For decades, cities have covered up highways to create usable public space, including the $110 million Klyde Warren Park in Dallas, Texas, that opened in 2012. Atlanta; Austin, Texas; St. Paul, Minnesota; and other cities are pushing ahead with proposals aimed at addressing racial inequities.

Nashville's Jefferson Street was a vibrant corridor of stores, barbershops, churches, restaurants and nightclubs before the interstate came through. Muddy Waters, James Brown, Etta James, Ray Charles, Little Richard, B.B. King, and Jimi Hendrix played there. The historically Black colleges of Fisk University, Tennessee State University and Meharry Medical College energized the area, and students from those campuses gave the civil rights sit-ins in the city their heartbeat.

In 1955, as plans for a federal interstate system took shape, a preliminary route was proposed that would have wiped out some white-owned and -operated businesses, according to the Tennessee State Library and Archives.

In 1967, after the route was changed to its current course, Love Sr. and other residents sued, alleging racial discrimination meant to harm North Nashville, its Black businesses and higher education institutions. The case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to hear it.

Some 128 businesses were demolished or relocated, making up almost 80% of Nashville’s African American proprietorships, the state library says.

Love Sr. and his wife had moved nearby after living for years on Scovel Street, one block away from Jefferson, and the demolition plans caught them by surprise.

“Our homeplace was 2109 Scovel St., so I know that personally we never received any advance notice of a public hearing,” Love Sr. testified in 1967, saying they were “near the last to be notified” of the interstate route.

The idea of capping the interstate came up but never caught on, stalled by community distrust of the federal government, said Faye DiMassimo, Cooper’s senior transportation adviser.

This time around, prominent community leaders, companies and government officials have sent letters of support to the federal government. Among them: Amazon which plans to grow to 5,000 jobs at its new downtown Nashville office and has committed $75 million in low-interest loans for new affordable housing; the state Department of Transportation, which will aid in design and construction; and some of the historically Black colleges.

“Nashville has sustained dynamic economic growth for the last decade-plus: Social, environmental, and infrastructural challenges accompany such success,” wrote Dr. James Hildreth, Meharry Medical College's president. “The proposed cap over I-40 is an important project in this respect, offering a major step forward for bringing shared prosperity to an historically marginalized public.”

Love Jr. still has the records of what the government paid for his family's Scovel Street house to make way for the freeway: $5,500 in 1966, the equivalent of about $47,000 today. For families like his who were handed similar checks to give up their homes, he sees the cap project as vindication for everything his father saw coming.

“I think my father understood very intimately that those who would be left would be damaged, those who had their houses taken certainly would be damaged,” Love Jr. said. “I think that’s the point we’re trying to make, that this interstate cap can help repair a lot of that.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks