Spy agencies' focus on China could snare Chinese Americans

China is the foremost challenge for U.S. national security agencies, a so-called “hard target” that is America’s chief rival for global dominance

As U.S. intelligence agencies ramp up their efforts against China, top officials acknowledge they may also end up collecting more phone calls and emails from Chinese Americans, raising new concerns about spying affecting civil liberties.

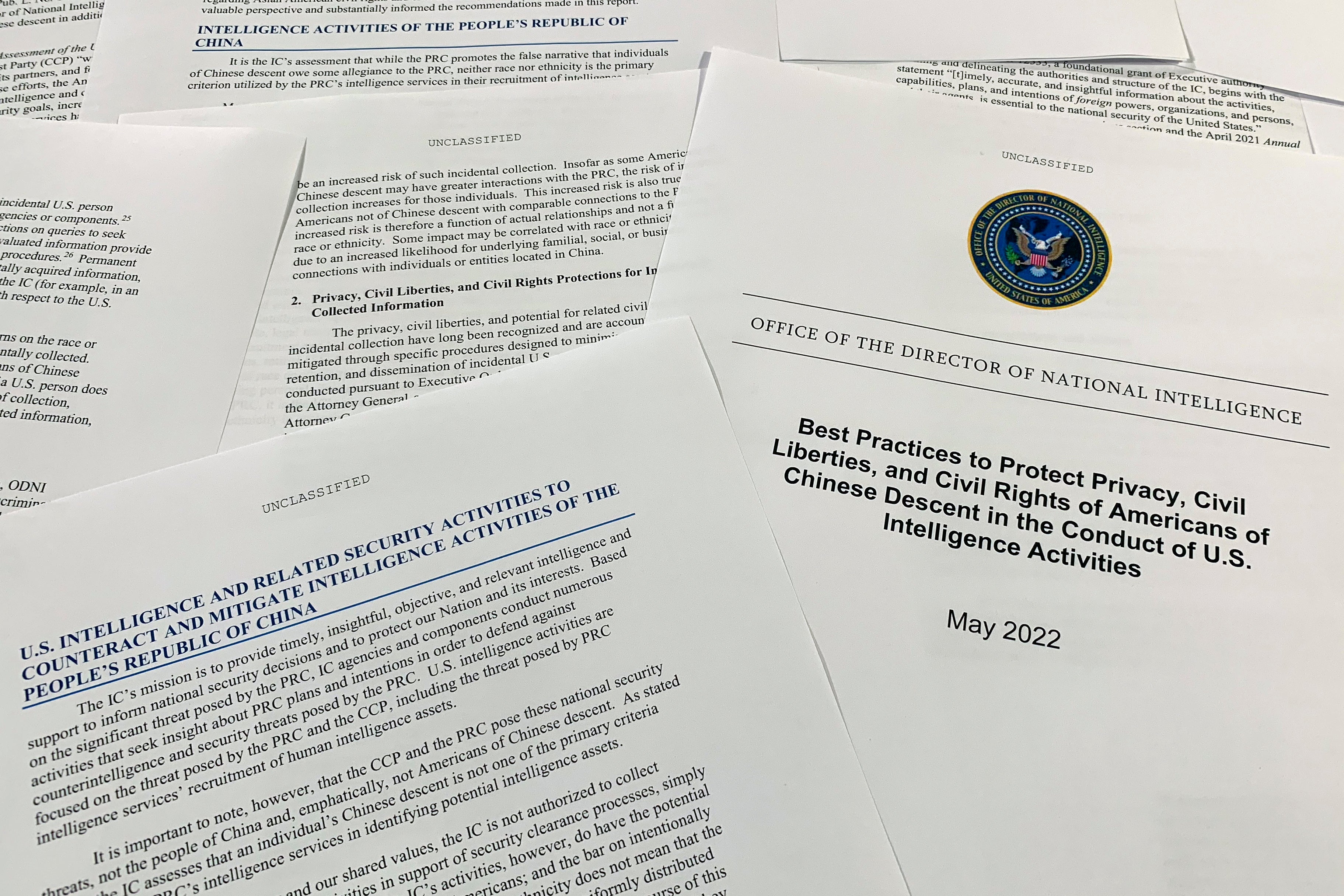

A new report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence makes several recommendations, including expanding unconscious bias training and reiterating internally that federal law bans targeting someone solely due to their ethnicity.

U.S. intelligence agencies are under constant pressure to better understand China's decision-making on issues including nuclear weapons,geopolitics and the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic — and have responded with new centers and programs focusing on Beijing. While there's bipartisan support for a tougher U.S. approach to China, civil rights groups and advocates are concerned about the disparate effect of enhanced surveillance on people of Chinese descent.

As one example, people who speak to relatives or contacts in China could be more likely to have their communications swept up, though intelligence agencies can't quantify how often due in part to civil liberties concerns.

There’s a long history of U.S. government discrimination against groups of citizens in the name of national security. Japanese Americans were forced into internment camps during World War II, Black leaders were spied upon during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and mosques were surveilled after the Sept. 11 attacks. Chinese Americans have faced discrimination going back to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first law to explicitly ban immigration from a specific ethnic community.

Aryani Ong, co-founder of the advocacy group Asian American Federal Employees for Non-Discrimination, noted that people of Asian descent are sometimes “not fully trusted as loyal Americans.” She said the report, published May 31, would be useful to conversations about what she described as the conflation of civil rights and national defense.

Ong and other advocates pointed to the Justice Department's “China Initiative,” created to target economic espionage and hacking operations by Beijing. DOJ dropped the name of the program after it had come to be associated with faltering prosecutions of Asian American professors at U.S. college campuses.

“Often we hear responses that we cannot weaken our national security, as if protecting constitutional rights of Asian Americans (is) contrary to our defense,” said Ong, who is Indonesian and Chinese American.

But in trying to produce demographic data on the impact of surveillance, the intelligence agencies say there's a paradox: Examining the backgrounds of U.S. citizens whose data is collected requires more intrusion into those people’s lives.

“To try to find out that type of information would require additional collection that would absolutely not be authorized because it isn’t for the foreign intelligence purpose for which the intelligence community gets its authorities,” Ben Huebner, the chief civil liberties officer for Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines, said in an interview.

But, Huebner added, “I think the fact that we can’t analytically get to those types of metrics doesn’t mean that we get to sort of drop the ball on this.”

One potential disparity highlighted by the report is what’s known as “incidental collection.”

In surveilling a foreign target, intelligence agencies can obtain the target’s communications with a U.S. citizen who isn’t under investigation. The agencies also collect phone calls or emails of U.S. citizens as they sweep for foreign communications.

The National Security Agency has vast powers to surveil domestic and foreign communications, as revealed in part by documents leaked by Edward Snowden. Under NSA rules, two people have to sign off on putting any new foreign target under surveillance. The NSA masks the identities of U.S. citizens under federal law and intelligence guidelines and turns over potential domestic leads to the FBI.

The FBI can access some of the NSA’s collection without a warrant. Civil rights advocates have long argued that searches under what’s known as Section 702 disproportionately target minority communities.

The ODNI report notes that Chinese Americans “may be an increased risk of such incidental collection,” as are Americans not of Chinese ancestry who have business or personal ties to China. The report recommends a review of artificial intelligence programs to ensure they "avoid perpetuating historical biases and discrimination.” It also suggests agencies across the intelligence community expand unconscious bias training for people who handle information from incidental collection.

ODNI is also studying delays in granting security clearances and whether people of Chinese or Asian descent face longer or more invasive background investigations. While there is no publicly available data on clearances, some applicants from minority communities have questioned whether they undergo extra scrutiny due to their race or ethnicity. According to the report, U.S. intelligence assesses that “neither race nor ethnicity is the primary criterion utilized by the PRC's intelligence services in their recruitment of intelligence assets.”

Sen. Mark Warner, a Virginia Democrat who chairs the Senate Intelligence Committee, said in a statement that he welcomed the recommendations “to increase awareness of existing non-discrimination prohibitions and improve transparency around the security clearance process.”

But Sen. Marco Rubio, a Florida Republican who is the committee's vice chairman, said requiring new training on unconscious bias and cultural competency was a distraction.

“The Chinese Communist Party likes nothing more than when we are distracted by divisive, internal politics," Rubio said in a statement.

The ODNI report highlights FBI training on race and ethnicity as a “best practice” in the intelligence community. In a statement, the FBI said that there was “no place for bias and prejudice in our communities” and that law enforcement “must work to eliminate these flawed beliefs in our agencies to best serve those we are sworn to protect. The FBI said its agents are trained in “obedience to the Constitution” and in “treating everyone with dignity, empathy and respect.”

A senior NSA official, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive intelligence matters, said the agency currently requires unconscious bias training for managers and hiring officials, but not all employees. The NSA does train intelligence analysts on rules that prohibit the collection of intelligence for suppressing dissent or disadvantaging people based on their race, ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation, and is reviewing ODNI's recommendations.

The CIA late last year issued new instructions to officers discouraging the use of the word “Chinese” to describe China’s government. The guidance suggests referring to the leadership as “China,” “the People’s Republic of China” or “PRC,” or “Beijing,” while using “Chinese” to refer to the people, language or culture.

“It’s important to be clear that our concern is about the threat posed by the People’s Republic of China, the PRC — not about the people of China, let alone fellow Americans of Chinese or Asian descent,” CIA Director William Burns said in a recent speech at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “It is a profound mistake to conflate the two.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks