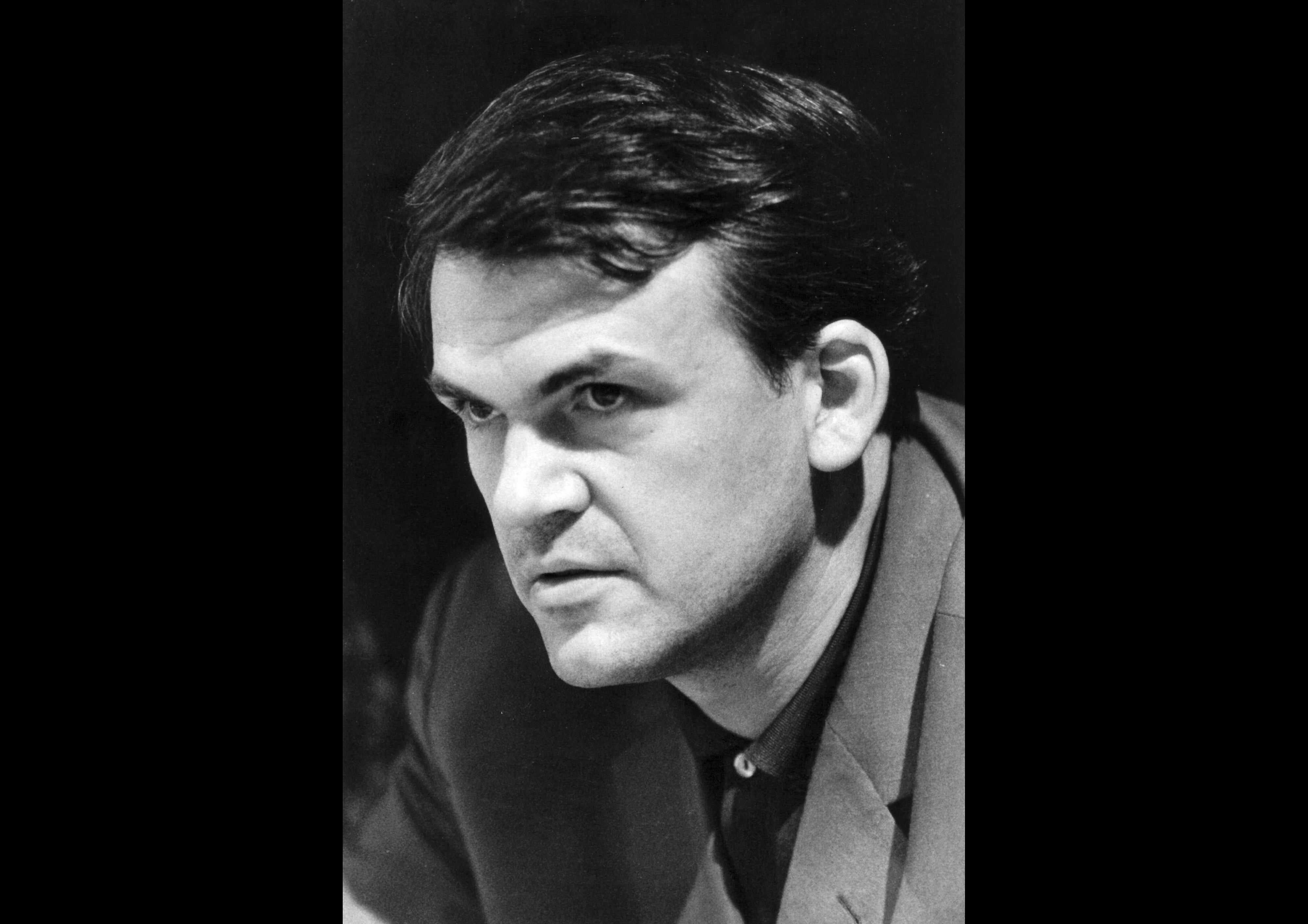

Milan Kundera, Czech writer and former dissident, dies in Paris aged 94

Milan Kundera, whose dissident writings in communist Czechoslovakia transformed him into an exiled satirist of totalitarianism, has died in Paris at the age of 94, Czech media said Wednesday

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Milan Kundera, whose dissident writings in communist Czechoslovakia transformed him into an exiled satirist of totalitarianism, has died in Paris at the age of 94, Czech media said Wednesday.

Kundera’s renowned novel, ``The Unbearable Lightness of Being,’’ opens wrenchingly with Soviet tanks rolling through Prague, the Czech capital that was the author’s home until he moved to France in 1975. Weaving together themes of love and exile, politics and the deeply personal, Kundera’s novel won critical acclaim, earning him a wide readership among Westerners who embraced both his anti-Soviet subversion and the eroticism threaded through many of his works.

“If someone had told me as a boy: One day you will see your nation vanish from the world, I would have considered it nonsense, something I couldn’t possibly imagine. A man knows he is mortal, but he takes it for granted that his nation possesses a kind of eternal life,” he told the author Philip Roth in a New York Times interview in 1980, the year before he became a naturalized French citizen.

In 1989, the Velvet Revolution pushed Communists from power and Kundera’s nation was reborn as the Czech Republic, but by then he had made a new life — and a complete identity — in his attic apartment on Paris’ Left Bank.

To say his relationship with the land of his birth was complex would be an understatement. He returned to the Czech Republic rarely and incognito, even after the fall of the Iron Curtain. His final works, written in French, were never translated into Czech. ``The Unbearable Lightness of Being,’’ which won him such acclaim and was made into a film in 1988, was not published in the Czech Republic until 2006, 17 years after the Velvet Revolution, although it was available in Czech since 1985 from a compatriot who founded a publishing house in exile in Canada. It topped the best-seller list for weeks and, the following year, Kundera won the State Award for Literature for it.

Kundera’s wife, Vera, was an essential companion to a reclusive man who eschewed technology — his translator, his social secretary, and ultimately his buffer against the outside world. It was she who fostered his friendship with Roth by serving as their linguistic go-between, and — according to a 1985 profile of the couple — it was she who took his calls and handled the inevitable demands on a world-famous author.

The writings of Kundera, whose first novel ``The Joke’’ opens with a young man who is dispatched to the mines after making light of communist slogans, was banned in Czechoslovakia after the Soviet invasion of Prague in 1968, when he also lost his job as a professor of cinema. He had been writing novels and plays since 1953.

“The Unbearable Lightness of Being” follows a dissident surgeon from Prague to exile in Geneva and back home again. For his refusal to bend to the Communist regime the surgeon, Tomas, is forced to become a window washer, and uses his new profession to arrange sex with hundreds of female clients. Tomas ultimately lives out his final days in the countryside with his wife, Tereza, their lives becoming both more dreamlike and more tangible as the days pass.

Jiri Srstka, Kundera’s Czech literary agent at the time the book was finally published in the Czech Republic, said the author himself delayed its release there for fears it would be badly edited.

“Kundera had to read the entire book again, rewrite sections, make additions and edit the entire text. So given his perfectionism, this was a long-term job, but now readers will get the book that Milan Kundera thinks should exist,” Ststka told Radio Praha at the time.