Ozone hole grows this year, but still shrinking in general

The ozone hole over Antarctica got bigger this year, which is unusual

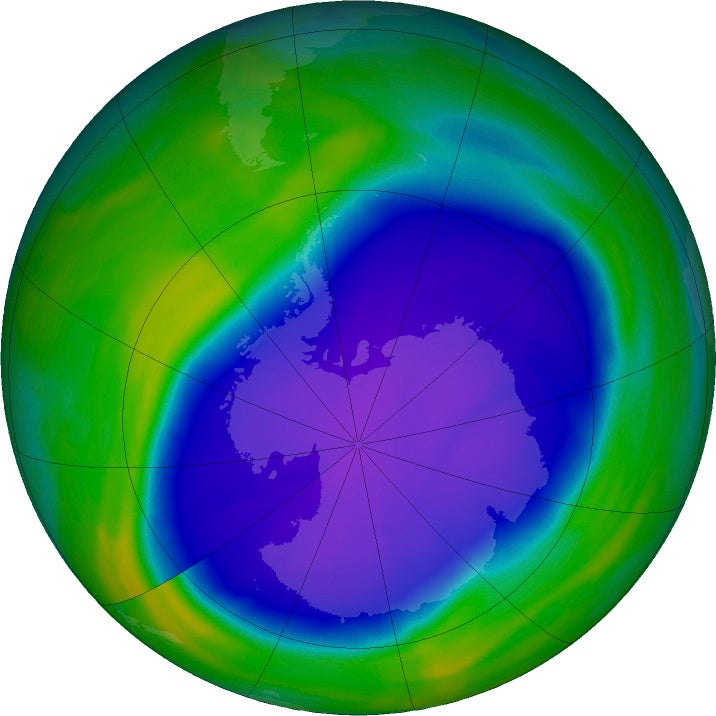

The Antarctic ozone hole last week peaked at a moderately large size for the third straight year — bigger than the size of North America — but experts say it’s still generally shrinking despite recent blips because of high altitude cold weather.

The ozone hole hit its peak size of more than 10 million square miles (26.4 million square kilometers) on October 5, the largest it has been since 2015, according to NASA. Scientists say because of cooler than normal temperatures over the southern polar regions at 7 to 12 miles high (12 to 20 kilometers) where the ozone hole is, conditions are ripe for ozone-munching chlorine chemicals.

“The overall trend is improvement. It’s a little worse this year because it was a little colder this year,” said NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Chief Earth Scientist Paul Newman, who tracks ozone depletion. “All the data says that ozone is on the mend.”

Just looking at the maximum ozone hole size, especially in October, can be misleading, said top ozone scientist Susan Solomon of MIT.

“Ozone depletion starts LATER and takes LONGER to get to the maximum hole and the holes are typically shallower” in September, which is the key month to look at ozone recovery, not October, Solomon said Thursday in an email.

Chlorine and bromine chemicals high in the atmosphere eat at Earth’s protective ozone layer. Cold weather creates clouds that releases the chemicals, Newman said. The more cold, the more clouds, the bigger the ozone hole.

Climate change science says that heat-trapping carbon from the burning of coal, oil and natural gas makes Earth’s surface warmer, but the upper stratosphere, above the heat-trapping, gets cooler, Newman said. However, the ozone hole is slightly lower than the region thought to be cooled by climate change, he said. Other scientists and research do connect cooling in the area to climate change.

“The fact that the stratosphere is showing signs of cooling due to climate change is a concern,” said University of Leeds atmospheric scientist Martyn Chipperfield. The worry is that climate change and efforts to reduce the ozone hole get intertwined.

Decades ago atmospheric chemists noticed that chlorine and bromine was increasing in the atmosphere, warning of massive crop damages, food shortages and huge increases in skin cancer if something wasn’t done. In 1987, the world agreed to a landmark treaty, the Montreal Protocol, that banned ozone-munching chemicals, often hailed as an environmental success story.

It’s a slow process because one of the chief ozone-munching chemicals, CFC11, can stay in the atmosphere for decades, Newman said. Studies also show that CFC11 levels going into the air were rising a few years ago with scientists suspecting factories in China.

Chlorine levels are down almost 30% compared to their peak 20 years ago, Newman said. If these cool temperatures had occurred with chlorine levels of the year 2000 “it would have been a very very large hole, much, much bigger than it is now.”

It’s the third straight year of an ozone hole peaking at more than 9.5 million square miles (24.8 million square kilometers), which Solomon called very unusual and worthy of extra study.

University of Colorado's Brian Toon points to large fires in Australia and injection of massive amounts of water from January's undersea volcano eruption as new phenomena that could be having impacts.

___

Follow AP’s climate and environment coverage at https://apnews.com/hub/climate-and-environment

___

Follow Seth Borenstein on Twitter at @borenbears

___

Associated Press climate and environmental coverage receives support from several private foundations. See more about AP’s climate initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.