Gene therapy for severe hemophilia is approved by FDA

U.S. health regulators have approved a gene therapy for the most common form of hemophilia

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

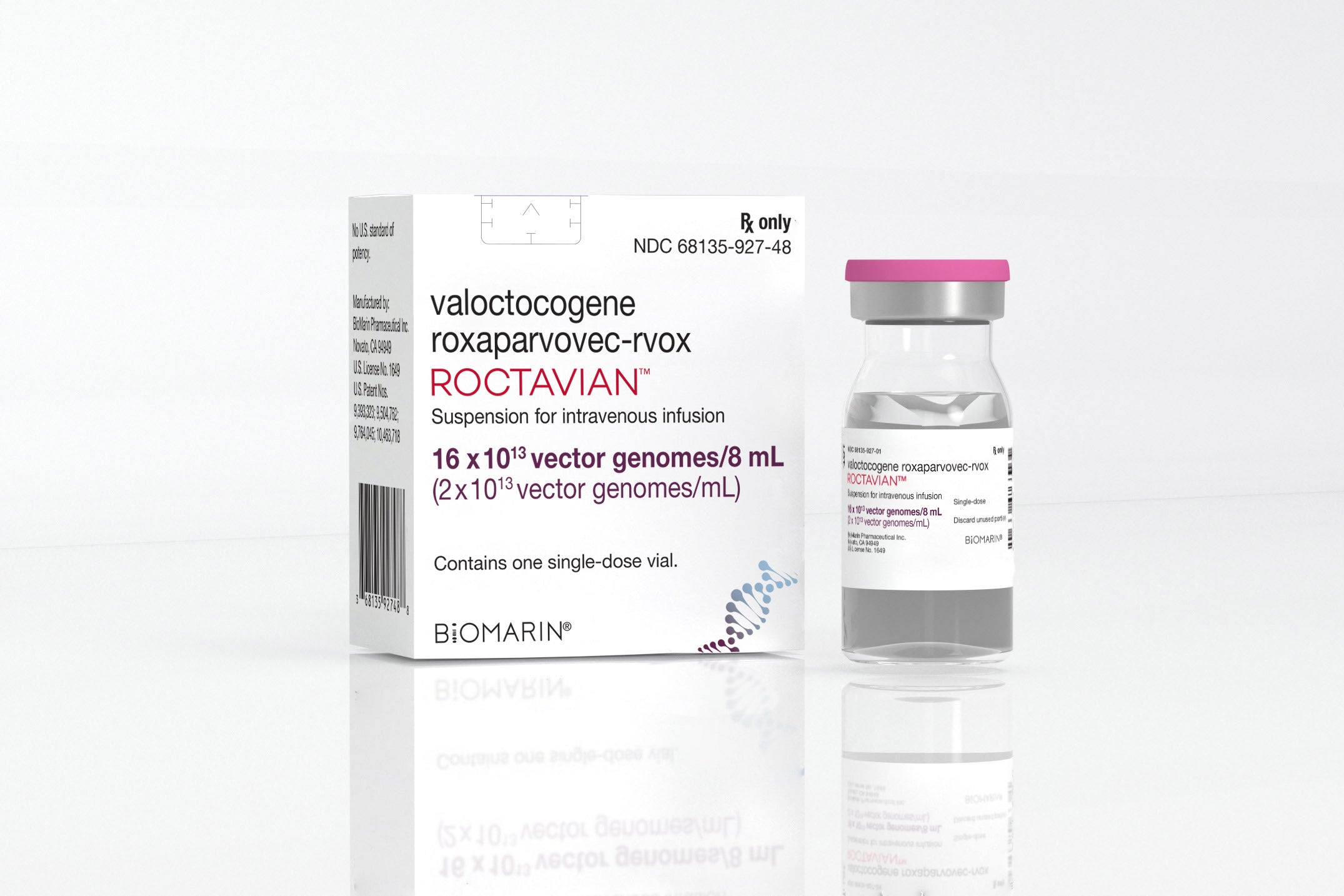

Your support makes all the difference.U.S. officials on Thursday approved drugmaker BioMarin's gene therapy for the most common form of hemophilia, an infused treatment that can significantly reduce dangerous bleeding problems.

The Food and Drug Administration approved Roctavian for adult patients with severe cases of hemophilia A, the inherited blood-clotting disorder that can lead to bleeding after minor injuries or scrapes. It's the first gene therapy for those patients.

The IV therapy is a long-awaited alternative to current treatments, including weekly doses of a protein needed to help blood clot. Some patients take a newer, longer-acting biotech drug that replaces the protein.

BioMarin said in a statement that the FDA approval was based on a three-year study showing a 50% reduction in annual bleeding incidents among 134 patients who received the treatment. Most patients continued to respond to the treatment beyond three years, without needing regular IV infusions, the company said.

BioMarin did not immediately announce the price. A similar gene therapy approved last year for hemophilia B was priced at $3.5 million, making it the most expensive one-time treatment of its kind.

Gene therapy developers have typically justified their prices by arguing that the treatments will ultimately lower health care costs by reducing the need for repeat procedures and care over many years.

Hemophilia is caused by mutations that prevent the production of proteins needed for blood clotting. Hemophilia A is the most severe variant of the condition, and some patients can experience spontaneous bleeding even without any injury. Left untreated, the condition can cause bleeding that seeps into joints and organs, including the brain.

Roctavian uses an inactivated virus, created in a lab, to deliver a replacement gene to the liver cells that produce the clotting protein. When the therapy is successful, patients can then produce the protein themselves. The label warns that rare, severe allergic reactions can occur.

Dr. Margaret Ragni called Roctavian “a major improvement in terms of reducing the burden of disease.” But she notes that many patients are comfortable with their current treatments and may be hesitant to try a new gene therapy.

“I think there’s a group that will want to do this, but patients need to hear what the risks and benefits are,” said Ragni, who treats patients at the Hemophilia Center of Western of Pennsylvania in Pittsburgh.

BioMarin was among the first companies to begin testing an experimental gene therapy in patients more than six years ago.

The San Rafael, California-based company excluded patients with certain potentially complicating conditions, including liver disorders and resistance to the standard blood clotting protein, which often develops in some hemophilia patients. BioMarin’s president for research and development, Dr. Henry Fuchs, said the company is conducting studies in some of those excluded groups to see if they can safely receive the therapy.

Another key question is how long the therapy’s benefits last. BioMarin has followed the patients for more than three years and they continue to experience reduced bleeding. But levels of the clotting protein in the bloodstream fall over time, suggesting additional treatments may eventually be needed.

“Let’s make sure the expectation isn’t that this is taken one time, forever and it will work perfectly for the rest of your life,” Fuchs said, adding “at some point we’ll know a lot more about durability."

Roctavian was approved in Europe last August, but the therapy has faced pushback from government health programs over its cost.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.