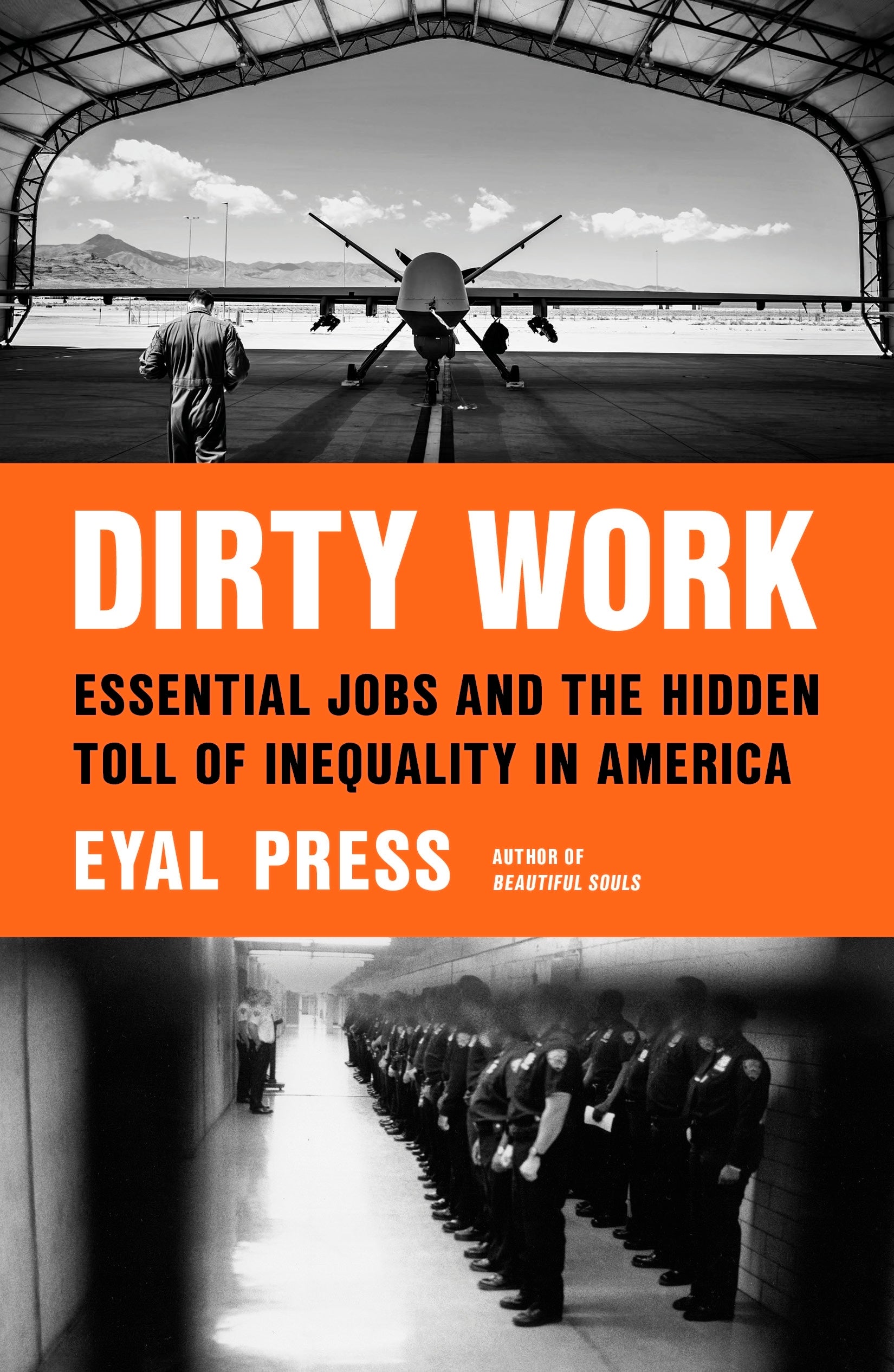

Review: 'Dirty Work' argues that unpleasant jobs hurt us all

The author of “Dirty Work” contends that while our society relies on military drone pilots, meat-packers, prison guards and others who perform what author Eyal Press calls “essential but morally compromised” tasks, we are increasingly shielded and distanced from these activities

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Dirty Work: Essential Jobs and the Hidden Toll of Inequality in America ” by Eyal Press (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

In “Dirty Work,” flying military drones, patrolling a prison and processing meat emerge as morally suspect occupations that not only carry outsized emotional challenges, but the work disproportionately falls to people of color, immigrants and low-income workers with few other options.

That moral assertion is up for debate. For sure, cutting up chickens all day and shrink-wrapping them in foam trays lacks the intellectual challenge of designing a building. But everyone who eats owes a debt to those food-line workers.

And that U.S. Air Force drone pilot, whose aircraft bristles with with lethal weaponry? Not only is the pilot safer but the use of such aircraft allows far more precise strikes than conventional aircraft.

The book is best at describing the emotionally numbing nature of some dirty work — killing animals all day, for example; it is less sure-footed in weaving together a cohesive thesis. Yes, many jobs in America are monotonous, dangerous, emotionally wrenching and, potentially, morally wobbly.

But an ethical prison guard provides a worthy service; he shares no guilt with the guard who uses his authority to beat inmates and contribute to the moral unraveling Press fears.

And are the thug prison guards, border patrol police and meat processing workers enough evidence to suggest a larger, national lapse of principles? That’s a harder case to prosecute.

Ultimately, the benefit in Press’s book is that it compels us to think about the work we create, who does it and how it fits into our national values and purpose. Press has performed a worthy service in launching a conversation about that.

But don’t expect national hand-wringing, soul-searching or clamors for congressional hearings.

Dirty jobs have been part of human existence since the beginning; the difference now is that many of them toil in remote towns out of sight of the rest of us.

And, as Press notes, much of America’s dirty work is performed by immigrants and people of color so glad to have a paying job that they not only endure abuse but sink to the bottom of America’s employment caste system. Their work is out of sight, and they are, too.