A bright window into David Hockney's own faith

The artist would not paint the Queen, but he made her a stained-glass window. Farah Nayeri reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On a drizzly September morning, David Hockney sits in his skylit London living room, puffing on a cigarette. The walls are covered with his art: framed self-portraits, tender etchings of his dogs and a large, brightly coloured composite photograph.

Leaning against one wall is a poster-size image of his latest creation: a stained-glass window for Westminster Abbey to commemorate the 65th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth’s reign. Measuring 28 feet by 12 feet, “The Queen’s Window” represents a hawthorn, a thorny floral shrub, blooming in a joyous profusion of reds, blues, greens and yellows.

“The hawthorn is celebratory: it’s as though champagne had been poured over bushes,” says Hockney, 81.

He says he reworked the design for the window from an earlier painting using an iPad. Hockney has used new technology extensively throughout his career and has exhibited works created with iPhones and Polaroid cameras alongside his paintings in some of the world’s most important museums.

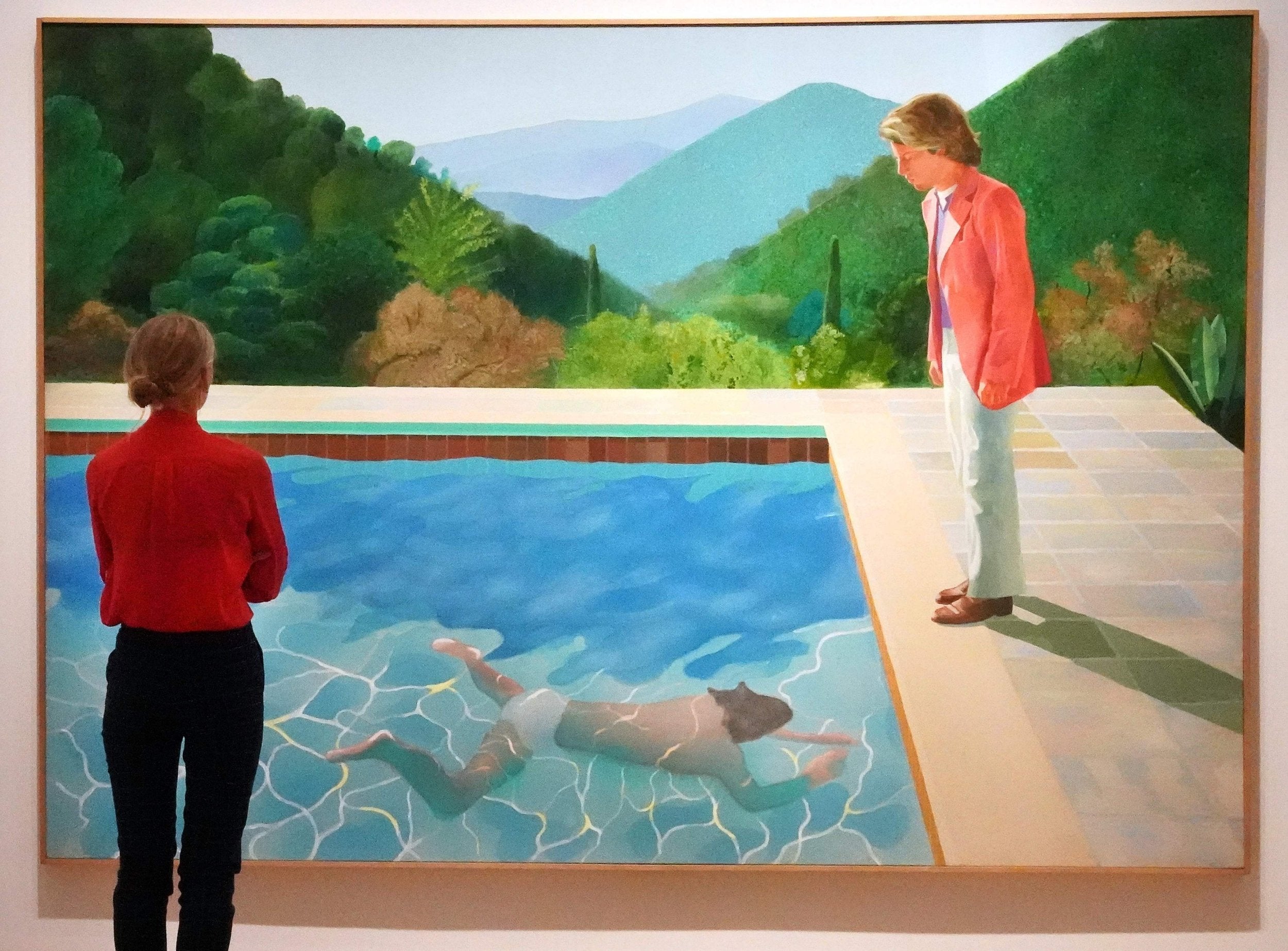

His 2017/18 retrospective, shown at Tate Britain, the Pompidou Centre in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, was a huge hit, and his market prices have soared since. “Portrait of an Artist (Pool With Two Figures)” (1972), up for auction at Christie’s in November, carries an $80m (£60m) estimate, which, if realised, would make him the world’s most expensive living artist.

Standing beneath Hockney’s window in Westminster Abbey days later, the Very Rev Dr John R Hall, dean of the church, says he approached Hockney because he was “the most celebrated living artist” and one whose fame coincided with the queen’s reign. He calls the work “absolutely vibrant”, and adds, “It’s very legible, so in that sense it’s very accessible, and I think people will be very excited by it.” He contrasts it with the 19th-century window next to it, representing the miracles of Christ, “so dark it’s almost illegible”.

Helen Whittaker, the stained-glass artist who led the 10-person team that produced the window from Hockney’s design, says the only element of it that Hockney painted on himself was his signature. (That glass fragment was flown to and from Los Angeles, where Hockney lives.)

“It was a joy to work with him because he’s very respectful of what we do,” she says. “We’re very grateful that he’s putting our profession on the map, because stained glass is always seen as the poor sister to the art world.”

Stained glass might seem an old-fashioned medium for a sought-after contemporary artist. Yet “it leads on very well from all the work he’s been doing on iPads and iPhones,” says art critic Martin Gayford, who has written books on Hockney. “When he started working on his first iPhone, which was in about 2009, he compared it to stained glass, the point being that an image on the screen is illuminated, so formally it links quite well.”

Hockney is one in a long line of modern and contemporary artists working in the medium. After the wartime destruction of churches across Europe – 2,000 were built or rebuilt between 1950 and 1965 in France alone – many painters were commissioned to make windows.

Well-known examples of the genre are Matisse’s dazzling blue and yellow designs for the Rosary Chapel in Vence, France; Chagall’s windows for churches in England, France and Germany; and Gerhard Richter’s abstract squares in Cologne Cathedral.

Stained glass is “essentially an architectural medium, and its relationship to the building is critical,” says Brian Clarke, a British artist who has created windows for architects such as Zaha Hadid, Norman Foster and I M Pei. While it is now being used in civic buildings, he says, there is “a tremendous danger of it becoming extinct, because it has become so universally associated with the church.”

“The greatest service that an artist can pay to the medium of stained glass is to use it for creating great art,” he adds.

Hockney is not much of a churchgoer. Though his mother was a “keen Christian” and he grew up attending a Methodist chapel, he says, he stopped at age 16 because, “I realised all the people who went to church weren’t really that good; they were hypocrites. That put me off.”

Today, he has his own form of faith, he says. “I used to think I was heading for oblivion, and I still really think that,” he says. Nonetheless, he has “a personal God,” because, “OK, you’ve got the big bang, but what’s before the big bang? I mean, you’re always going to ask, aren’t you?”

As a church, Westminster Abbey could not be more intimately linked to the monarchy. Thirty-eight sovereigns have been crowned there, and 17 are buried on site. Hockney would not seem an automatic choice for it. The onetime bad boy of British art has spent the better part of the past five decades in Los Angeles, and in 1990 turned down a knighthood, though he is no adversary of the monarchy, he says. “I was living in California. I didn’t really want to be Sir Somebody,” he explains.

And when he was later asked to paint the Queen, he turned that down, too. In our interview, he recalls the painter Lucian Freud’s depiction of the monarch. “He got 10 hours from her, which is not very much for him, but a lot for her to sit,” Hockney says. “I knew the portrait. It was OK. But I’m not sure how to paint her, you see, because she’s not an ordinary human being.

“She has majesty,” he adds. “How do you paint majesty today?”

While Hockney’s market standing has made him rich, he says the extra money hasn’t changed his life – “What am I going to do with it?” – and that what he loves most is being in the studio, which makes him feel 30 again.

“An artist can’t really be a hedonist, because he’s a worker,” he says.

His only vice now, he says, is smoking, but he has no apologies for that. He points out that Picasso and Monet died in their 80s or 90s. “If all you’re aiming for is longevity, it’s life-denying,” he says.

The window in the abbey wasn’t about establishing a legacy, he says: “Everything turns to dust eventually. Even Westminster Abbey will.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments