High Court state pension loss highlights female funding crisis

Wake up call for all women as millions risk old age poverty

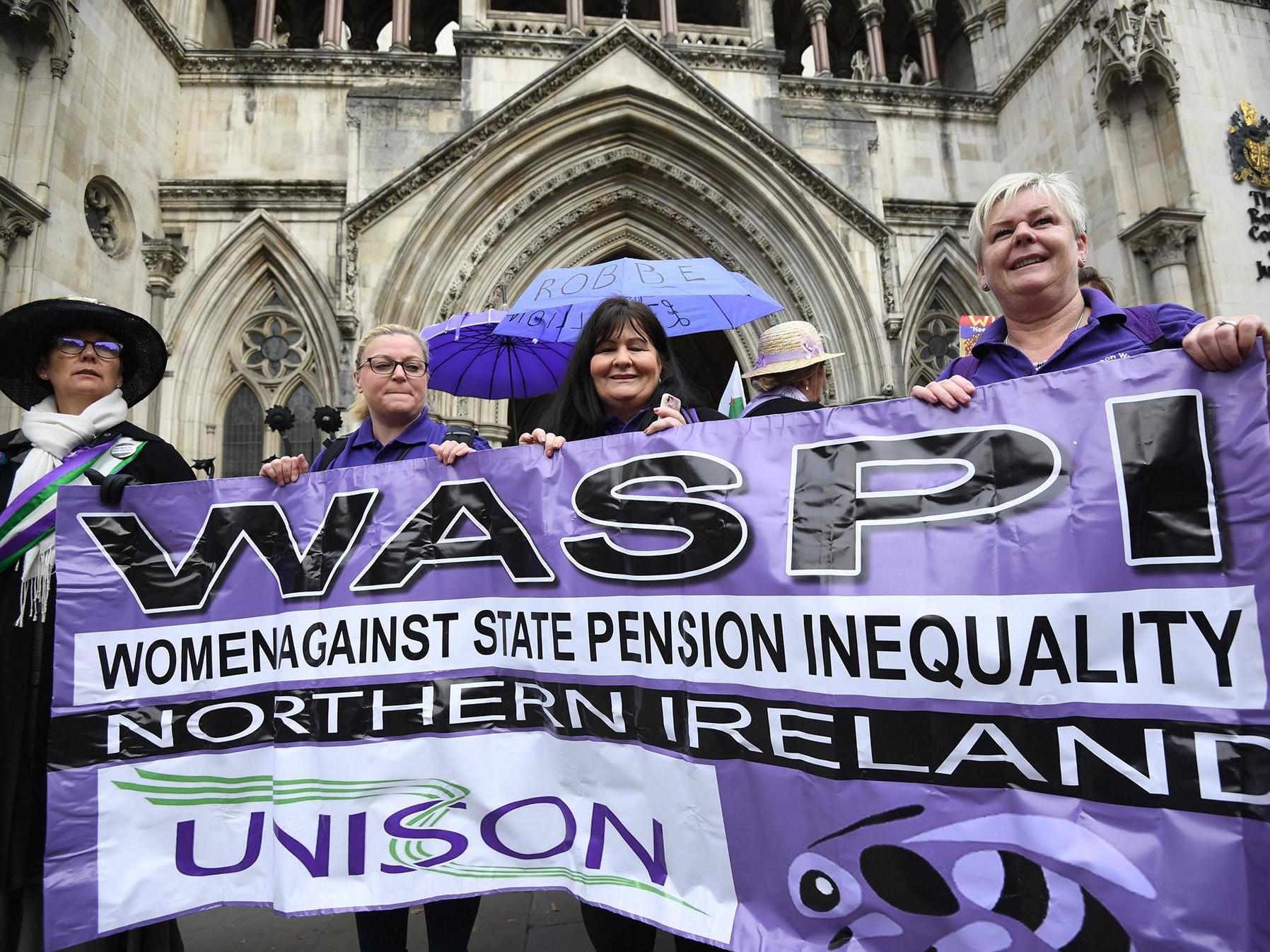

Campaigners, including high profile politicians, have vowed to fight on after losing a High Court battle against the government for the way it handled recent increases to the state pension age for women.

Millions of women have been affected by changes in the age that they start to receive their state pension made to balance the point that both sexes receive state support for later life.

The retirement age for women increased from 60 to 65 between 2010 and 2018 to come into line with men in a move that affected almost four million women. The state pension age is now gradually increasing for both until it reaches the age of 68. Further rises are expected in the coming decades as increased longevity takes its toll on a state system that is already feeling the funding strain.

Homelessness and suicidal thoughts

To say the changes so far have been controversial would be a monumental understatement, not because of the underlying reasons for the changes, but because of the way they were handled.

After more than 60 years of a consistent female retirement age, the plans to increase the state pension age for women were first announced 20 years ago on a gradual timetable that was then speeded up by successive governments.

This led to hundreds of thousands of women born in the 1950s not finding out they wouldn’t get their state pension for several more years until they were almost at the point of retiring leaving precious little time to plug the gap.

Because of the way the changes were made, many women found that simply being born a few months on the “wrong side” of the cut-off could mean their state pension payments was be delayed by years.

The effect on some has been devastating.

The way the Department for Work and Pensions handled the changes and the way they were communicated, the campaigners believe, constituted discrimination on sex and age grounds. They had called on the government to pay back the difference in the retirement income they had expected, which could have totalled £40,000 per person. But the High Court this week ruled that the rise was not discriminatory.

Down but not out

Jon Greer, head of retirement policy at Quilter: says “It had been claimed that if the equalisation of state pension ages between men and women were to be reversed it could cost the government in excess of £180bn, so from their perspective they will be very relieved, particularly given current concerns about state pension funding as it is.

“The review made note that the government acted in a lawful way, so it is inevitable that this decision will result in more political pressure placed upon the government to implement a change. Before coming to power, the prime minister did indicate it was an issue he was keen to sort out. As such, with a general election around the corner and the issue not going away anytime soon, this could become a key battleground to attract votes from a disaffected demographic.

Wake up call

But regardless of whether Boris Johnson will deliver on his promises to assist these women – made during his campaign to secure No 10 this summer – the blow piles further pressure on a huge financial problem facing women in old age.

With worrying numbers of people of both sexes assuming the state will provide their income in old age, further retirement age changes, tax tweaks and other legislative tinkering will continue to peel away layers of financial security at a time when women don’t have enough to start with.

World Economic Forum data released earlier this year reveals that Britons, in general, have an average of only 8.5 years’ worth of retirement saving. Men will outlast their funds by more than 10 years and women by almost 13 years, based on average savings at the point of retirement and assuming an income of 70 per cent of their pre-retirement salary.

“Our research shows that women are already at a disadvantage when it comes to investing during their working lifetime and in retirement, with 62 per cent of women in the UK saying they have never invested their savings and only 50 per cent have invested in a personal pension,” says Janine Menasakanian, head of distribution strategy, personal investing at Legal & General Investment Management.

“This is further capitulated because of an increase in women going into self-employment and not being auto-enrolled into their employer’s pension. In fact, depending on exactly what data you trust, just 10-20 per cent of all those freelancing in the UK currently pay into a pension scheme.

“However, these issues are not limited to women – many people in the UK are ill-equipped for when they reach retirement age. All investors – but especially those in their 40s, who are getting close to the end of their career need to be thinking about how they will plug their personal pension savings gap, for a secure future.”

Industry consensus is that workers should set aside roughly 12-15 per cent of their salary for retirement over their working lives, taking into account the state pension and the workplace pension scheme. The exact details will depend on your individual circumstances and the later you start saving, the higher the proportion you’ll need to set aside.

Calculators such as this one from the Money Advice Service provide a good basic starting point.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks