New definitions of poverty are re-defining financial hardship

Terms like ‘food poverty’, ‘fuel poverty’, and even ‘funeral poverty’ are being used by politicians and charities. But are they doing those on the breadline more harm than good?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.‘Poverty’ is in the middle of a rebrand. Last month, for example, a report by MPs warned that the soaring cost of funerals, combined with erosion in the value of state funeral grants, is forcing poorer grieving families into the clutches of payday lenders. This issue was widely described as ‘funeral poverty’.

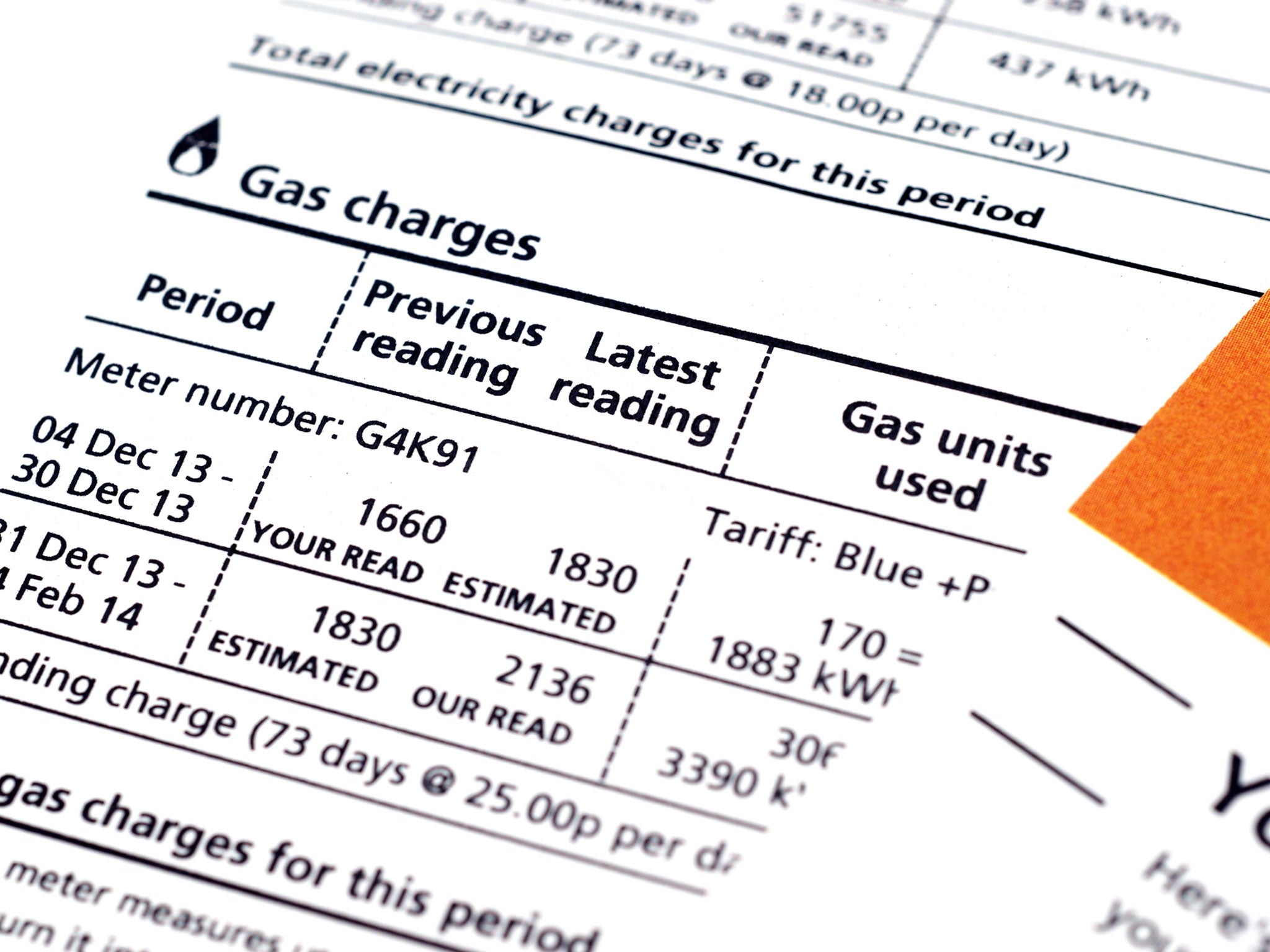

Meanwhile, food poverty is defined as a household being unable to afford an adequate and sufficiently-nutritious diet, which seems straightforward enough. However, fuel poverty is now defined by the state as having above average fuel costs that would leave the household below the official poverty line if they spent that amount – a more complex equation than the old system where it was defined as spending 10 per cent or more of a household’s income on fuel. The new official definition reduced the number of households considered to live in fuel poverty by a full million.

Of course, a key reason for specifying food poverty, energy poverty and funeral poverty is that the issues that arise as a result are undeniably serious. But experts argue that poverty is simply poverty, affecting all aspects of a household. Rebranding strains of poverty as a specific issue could be seen as a way for charities and pressure groups to prioritise their own preferred issues, or for the state to be seen as tackling an aspect of poverty without having to address the wider issues.

‘Plain, old-fashioned poverty’

Dr Bryce Evans is senior lecturer in history at Liverpool Hope University and runs a community kitchen in his spare time. He says: “Poverty is poverty full stop… the root cause of ‘food poverty’ is, of course, plain, old-fashioned poverty.”

But it is hard to define poverty without listing off specifics such as food or transport costs. In the UK, a household is considered to be in relative poverty if their after-tax income is below 60 per cent of the median household income, meaning a threshold of around £239 a week.

However, defining poverty that way is fraught with difficulties, as Dr John Simister, senior lecturer in economics at Manchester Metropolitan University, explains: “It's really hard to assess poverty. Imagine two families both earning £100 per week: one a couple without children, the other a single parent with many children - it's hard to say which family is poorer. Londoners get a London weighting but it's not usually enough to compensate them for higher rents or mortgage.

“So one approach is to find out their food spending or energy bills as a percentage of disposable income… But it's a very unreliable method [as] some well-off people might spend a lot of money in restaurants, which in my experience often tends to get counted with food spending rather than leisure.”

Perhaps a better definition is the relative deprivation theory of poverty, outlined by Professor Peter Townsend, which defines poverty as when someone’s “resources are so seriously below those commanded by the average individual or family that they are, in effect, excluded from ordinary living patterns, customs and activities”.

As one parent put it in a recent NCB report looking at the impact of fuel poverty on children: “Fuel poverty is when you wake up to find you have no gas, no money and two days 'til payday. You have to feed cold food to your children and wrap them up in coats, gloves and scarves indoors or trail them round the shops all day to keep warm.”

A definition like this clearly encompasses households that cannot afford to heat their homes sufficiently, or eat nutritious and adequate meals. However, it could also be considered to include other normal spending, such as being able to occasionally socialise or use a TV or the internet.

By highlighting specific struggles to heat and eat, there’s a risk that the wider elements of poverty will be seen as less of a concern, when they can in fact have a vast impact on a family’s wellbeing. Dr Simister adds: “For a family in London, a car is probably a luxury - but in some rural areas, a car is vital to get to shops, doctors [or] take kids to school.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments