What the Facebook data scandal means for your finances

Not too stressed about the Cambridge Analytica fallout? Perhaps you should be

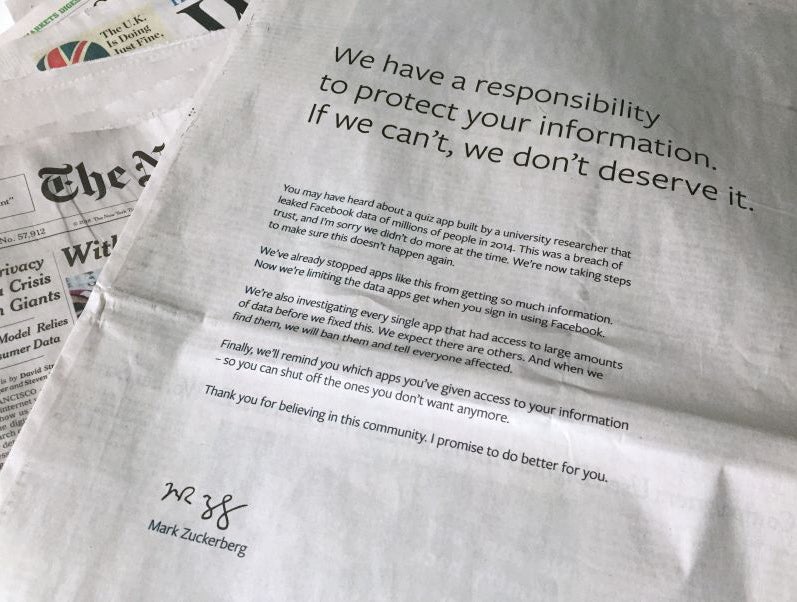

Facebook is so embarrassed by the Cambridge Analytica data scandal that it took out expensive adverts in UK and US media last week to apologise to its users. But if you were appalled by the way in which personal data on Facebook appears to have been manipulated for political ends, have you thought about how this data could also be used to target your finances? Data security experts warn that too few people understand how their information can make them vulnerable to financial crime.

In fact, Facebook and other social media sites offer crooks and fraudsters a treasure trove of data they could use to steal from you – in all sorts of different ways. And if you’re sharing your data or profile beyond your friends and family, you leave yourself even more open to attack.

The crime doesn’t even have to be online. Research published by the home security company ADT found that three-quarters of burglars now use Facebook or Twitter to target properties. People’s home addresses are easily found using social media sites, ADT warned, while posting pictures of possessions and valuables provides burglars with potential shopping lists; in several cases, thefts have taken place when people have posted about being on holiday, inadvertently letting burglars know their property is empty.

In other cases, fraudsters have taken advantage of posts from people travelling to target their friends and families – easily accessed via their social networks – with appeals for financial assistance. They pose as the traveller and ask for help urgently with the cost of, say, a health problem overseas; since friends and family know the traveller really is in the location cited, they’re more likely to fall for the scam.

As for online attacks, it’s worth reflecting on the nature of the app at the centre of the Cambridge Analytica scandal – a quiz that Facebook users completed for fun but which harvested a range of personal data from them. Similar techniques have been used to harvest data that is then exploited for fraudulent purposes.

For example, an app might ask you to provide your mobile phone number; this could be used to contact premium-rate telephone numbers – you won’t know you’ve been targeted until your bill arrives. In other cases, fraudsters have impersonated well-known brands to launch fake promotions that harvest sensitive data or invite people to change passwords with companies with which they have genuine accounts; this information is then used for fraud.

In other cases, data leaks may be completely out of your control. The consumer credit company Equifax, for example, maintains records of hundreds of millions of people around the world – in the UK, if you’ve ever applied for any kind of credit product, from a mobile phone contract to a mortgage, or if you’re on the electoral roll, the chances are that it will hold some personal data on you. Last year Equifax fell victim to a cyber security attack in which criminals stole the personal information of 145 million people, including 15 million in the UK.

Equifax says most of this data was simply contact information, though in a smaller number of cases email addresses may have been leaked – and even partial records of credit card numbers. It has subsequently written to all those affected warning them to keep a close eye on bank statements and other financial accounts, looking out for unauthorised transactions that the data could have been used to initiate.

In this environment, it is crucial to be as cautious as possible about the data you share online – both the nature of the information and who you make it available to. Don’t sign up to terms and conditions you haven’t read and understood, and be vigilant about your privacy.

New data laws that come into force in May will help with this. They’ll boost your rights to ask for details of all the data held on you by an organisation; they’ll also give you the right to “ask to be forgotten” – to have your data deleted. Be prepared to exercise these rights to keep your data footprint as small and manageable as possible.

Bear in mind that it’s not only crooks you need to look out for. The financial services industry is making increasingly sophisticated use of personal data generated in a whole host of different ways. If you don’t set clear limits about how your data is used, you could be disadvantaged.

It’s not inconceivable, for example, that your health insurer will one day soon have access to data from your supermarket loyalty card – perhaps revealing that your diet puts you at risk of certain health conditions and therefore prompting an increase in your premiums. Or imagine a life insurer refusing to offer you affordable cover after seeing pictures of you engaged in dangerous sports on social media.

In the banking industry, meanwhile, the launch of open banking at the beginning of this year was specifically aimed at encouraging customers to give organisations access to their bank account data. There may be lots of benefits from this – open banking supporters hope innovative companies will launch new services that exploit this data to help people to get better deals or manage their money more effectively. But you can also see how your data could be used against you, both by unscrupulous agents and companies that suddenly know more about you than you might want.

The bottom line is that the Facebook scandal has some very broad lessons. It’s a reminder that our personal data is precious – where we remain in control, willingly sharing information with partners we trust, there may be real benefits. But without vigilance this data could also be our downfall – financially, as well as politically.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks