Zines: How the internet helped a printed outlet for outsiders and nerds thrive

Home-made magazines are an increasingly popular, and commendably democratic, journalistic trend. Kashmira Gander takes a look between the covers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jade French was 14-years-old when she ripped out a handful of images from some magazines, crudely glued them to a piece of A4 paper, and photocopied sheet after sheet at her local corner shop. She was fed up with how she was being treated simply because she was a girl, and was going to let the world know about it. Thus began her first zine, Ladyfingers.

“I wrote about what people at school said when I and a group of female friends started a band. I wrote about what band promoters said to me when I would sit behind my drum kit before a gig. Mean comments, and always sexist. I didn’t know where else to put this ‘stuff’,” says French, now studying zines as part of her PhD at the University of Leeds.

That was 13 years ago, when Facebook was a twinkle in Mark Zuckerberg’s eye but the death toll for print had already been rung. Zines were an outlet for outsiders and nerds. But now, anything zines can do, surely online does better. So why still make them?

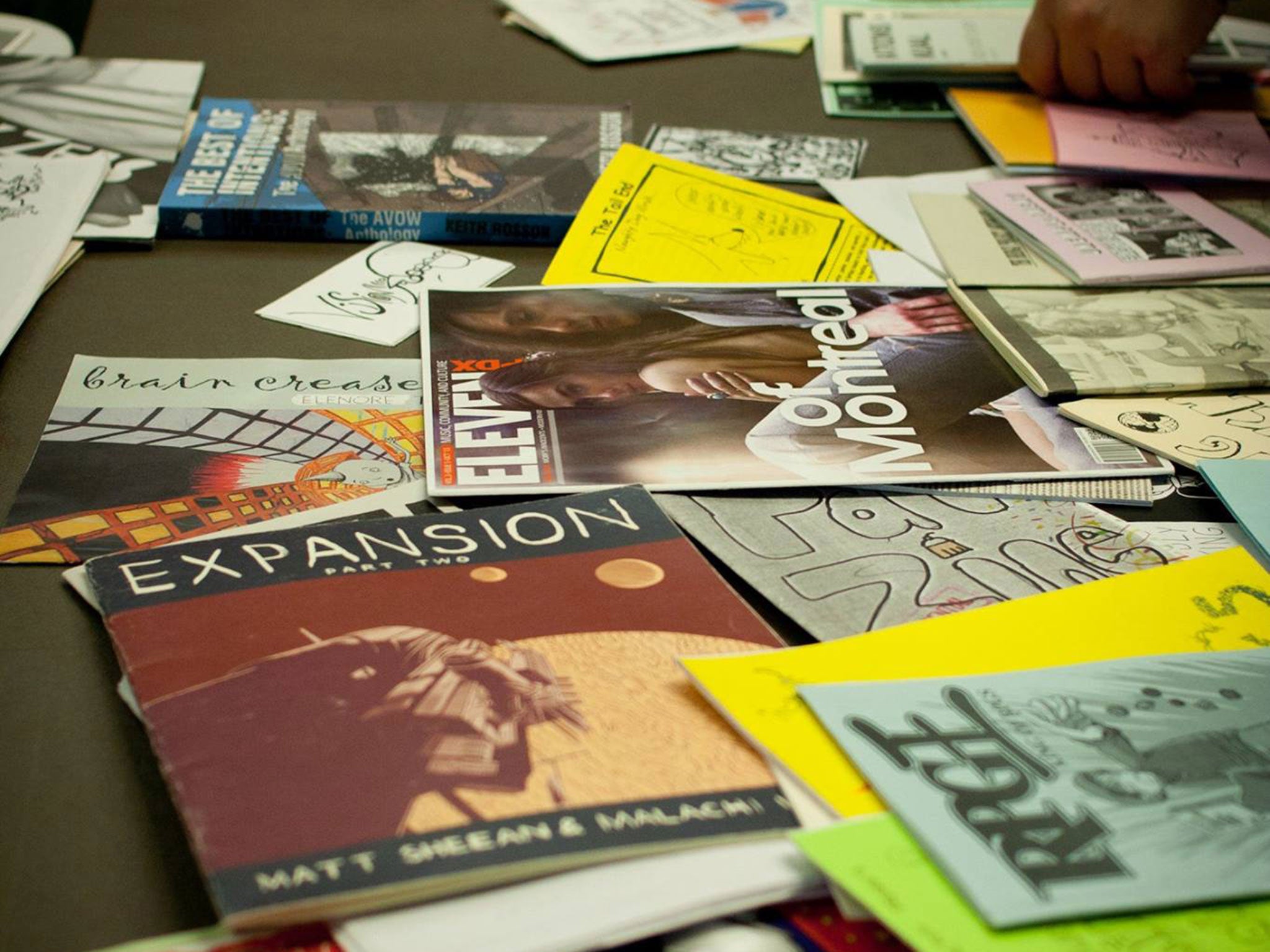

Because, remarkably, not only does French still make zines but the health of the zine scene is witnessed by the countless fairs held across the world, from San Francisco to Athens; among them, the DIY Cultures event taking place in east London today.

Of course, for French and many other zinesters, the creative process – and the market – has changed over time: sites such as Etsy offer space to sell copies, and social media is used to find readers and contributors; and in many ways, zines and the internet have shared goals. The saying “if it exists, it’s on the internet” goes for zines, too. And according to Ruth Jamieson, the author of Print is Dead: Long Live Print, which documents the rising popularity of independent magazines, “Digital was supposed to be this grim reaper of print,“ she says, ”but it’s been its biggest ally,”

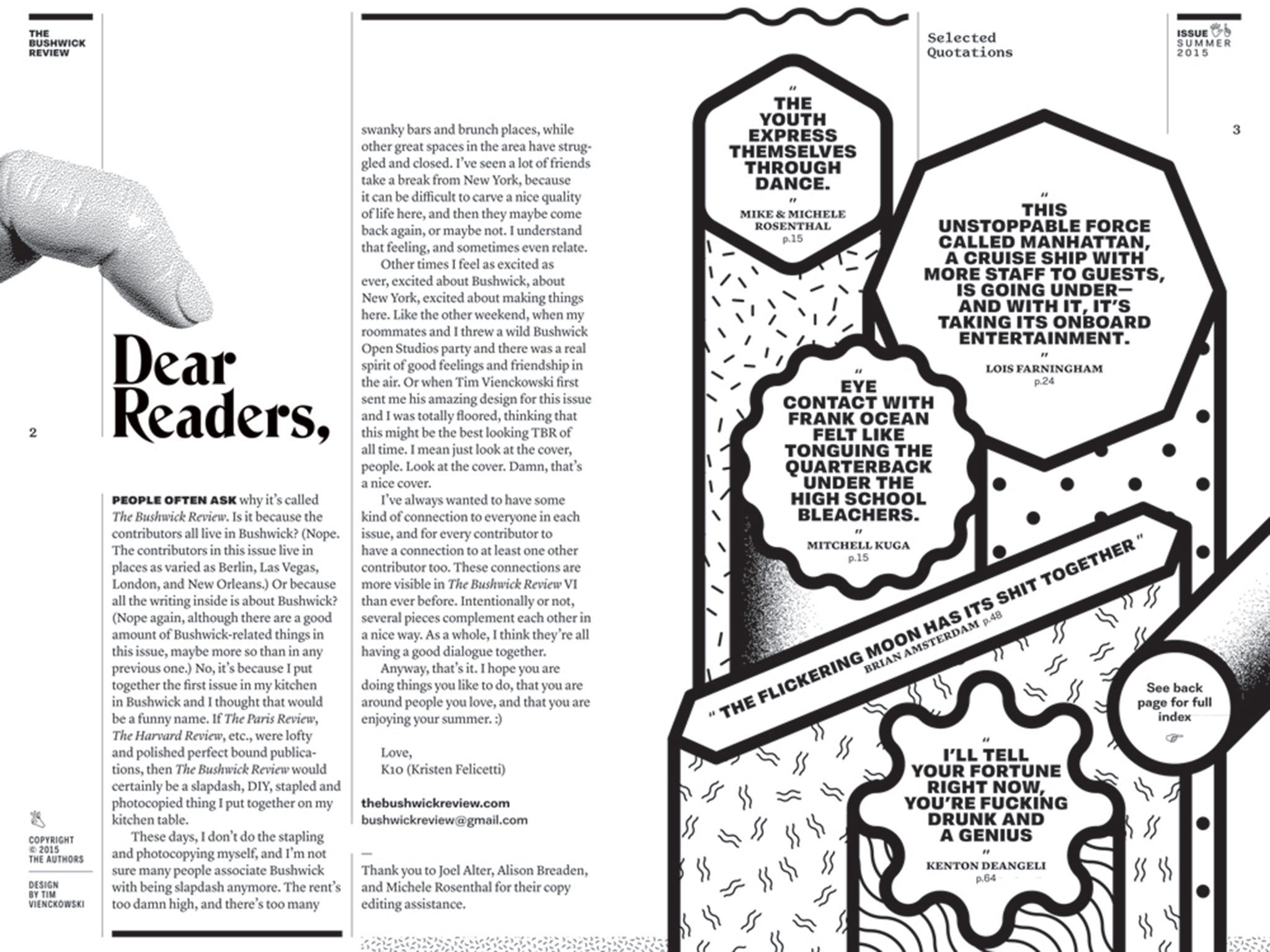

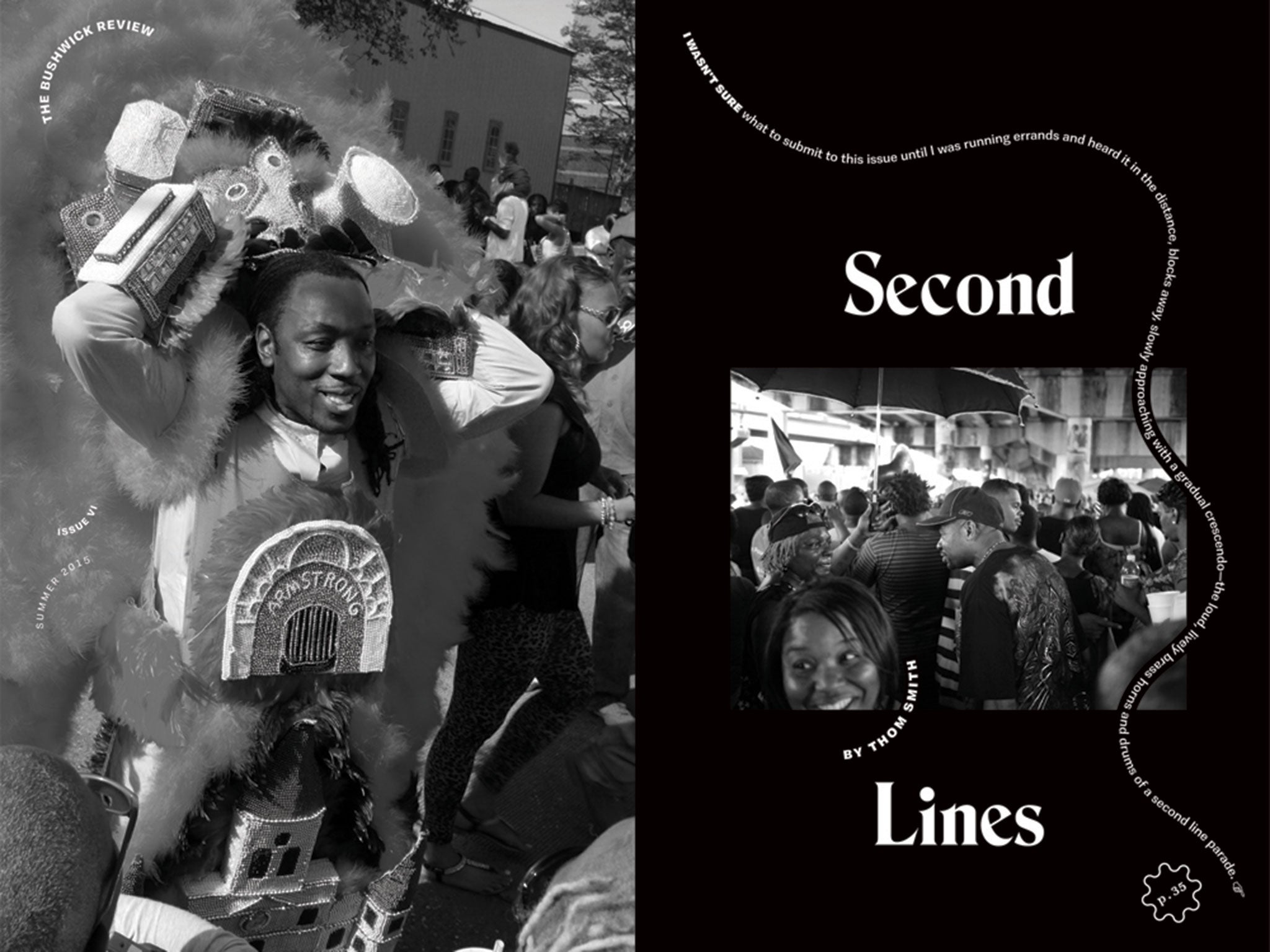

Certainly, there's no shortage of variety or opinion on the zine scene. For Kristen Felicetti, editor of The Bushwick Review zine, in New York, zine-making's almost a political act .“What I like is that anyone can make one, no one is standing around waiting for someone else's permission to make art or write. The zine makers are giving themselves the permission. And saying they deserve to be heard is subversive to me.”

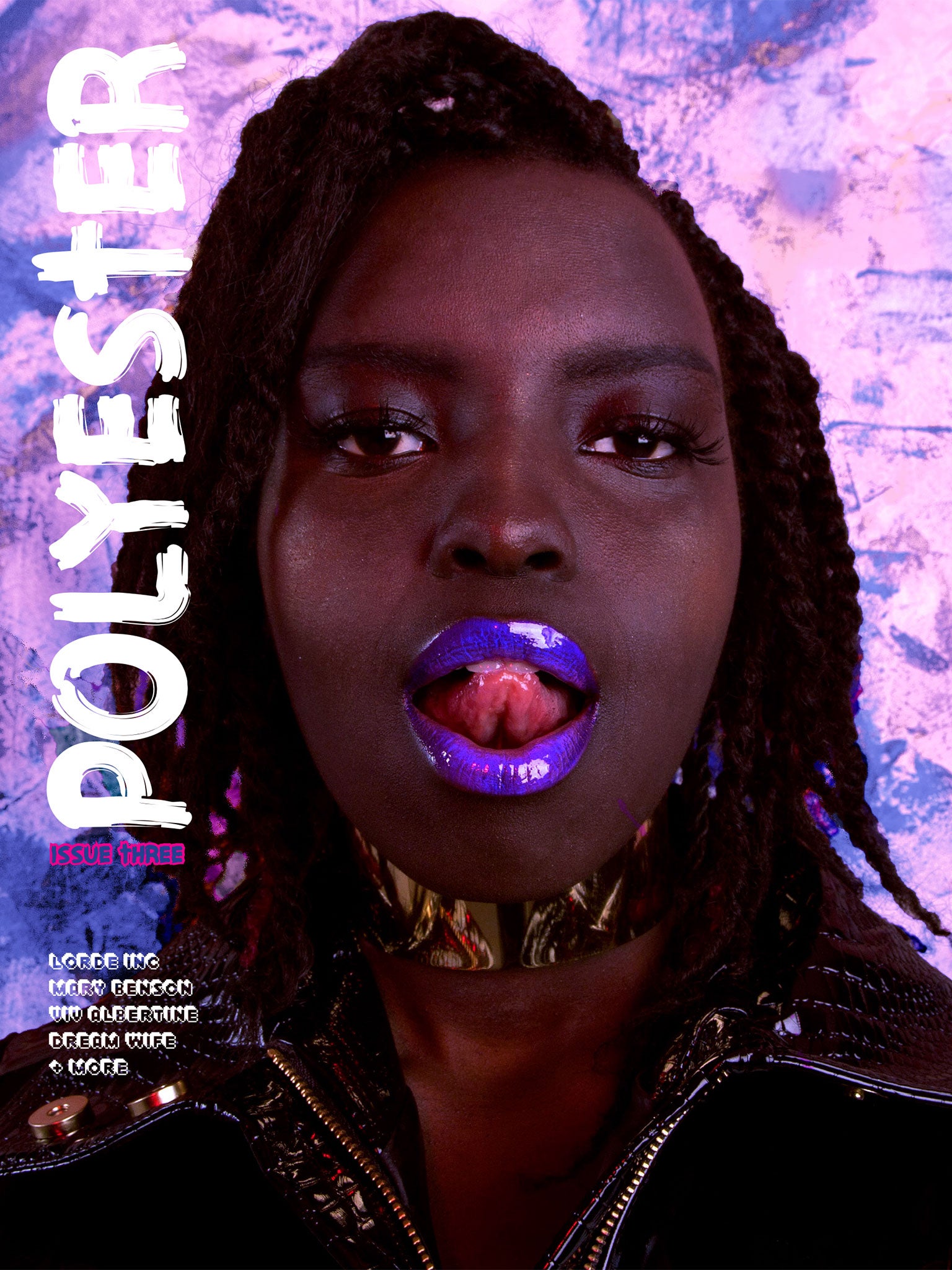

Reflecting the breadth of interest, the themes at this year’s DIY Cultures event in East London on 29 May include “radicalising mental health”, “decolonising libraries”, “shy radicals” and “the history of black arts magazines”. And then there's “intersectional feminism”, embodied by Polyester, a bi-annual A5-sized colour booklet which is an unashamed celebration of anything trashy and saccharine. (The photograph of a tampon covered in deep-red glitter on the back of its second issue gives an idea of its aesthetic.)

Its editor in chief Ione Gamble started the zine as a spin-off from a university project while studying fashion journalism. But as a 22-year-old, why didn't she head straight online, as one might expect?

Because, she says, the lack of restrictions allows the team to be “less timely” with their ideas. The pages, devoid of browser tabs or adverts, invite people to luxuriate their content without distraction.

Still, she and other zines makers stress that their projects aren’t nostalgic for a time before the internet or a total rejection of mainstream media. These media aren’t mutually exclusive. On the other hand, as Channing Kennedy, 35, the executive director of the San Francisco Zinefest says – recalling how a website he ran was once lost: “Zines are susceptible to mould and fire, but you'll never go look at one of your old zines to find that a multinational corporation has filed to make your it illegal to read in your country.”

Despite their varied interests, one thing seems to unite zine devotees: a love for printed publications that is hard to pin down. Sotiris Trecha, 25, who runs the Dream Colour photography zine in Athens, says that without mainstream magazines he wouldn’t have fallen in love with writing, but he never buys them any more because the content is free online.

Trecha instead prefers to add to his growing collection of zines and create his own. “In printed pages you have to actually choose carefully what you are going to print, instead of an infinite scroll down on a blog that you just want to steal someone’s attention as many more seconds as possible.”

Teal Triggs, Professor of Graphic Design at the RCA at the author of Fanzines, says: “As a reader - there is something appealing about being able to have contact through the act of receiving a zine from a producer directly; the conversation that ensues, and the personal connection through a shared subject interest. Also, of course, the tactility of print is not to be underestimated. “You can delve into subjects which perhaps flirt at the edges of radical or extreme content without censorship. It’s a “free’ space”.

It's certainly a fascinating one. The last one Channing Kennedy made was Notables, “a collection of found photos of barristers with made-up names under them, closed with a gold seal that had to be cut through to read it.” But that's nothing compared to the zine he traded with an eight-year-old girl at Long Beach Zinefest, near Los Angeles. “She was there with her parents, distributing copies of her new mini-zine, Caracal Facts, written and illustrated by her. True to its branding, it was a collection of facts about caracal cats. It folds out into a poster of a winking caracal cat, drawn by her.”

And as the internet becomes increasingly policed and homogenous, zines still offer a way for people to express themselves outside of the mainstream. As French says: “Many zinesters choose to print their content as opposed to publishing online to simply keep this engagement and community alive.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments