Runaway piglets and goat psychology: A woman's adventures in farming

'The hardest moments are always slaughter days. It gets easier but it never gets easy'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Did you know that electric fences only work on the un-wooled parts of sheep, like their noses? And that particularly motivated sheep will eventually work this out, too? Neither did former Navy officer Andrea Chandler until she dropped everything to become a farmer.

Chandler, 40, has been documenting the highs and lows of farming in the small town in the piedmont of Virginia on her brilliantly dry-humoured Twitter account. In nine days, she has garnered over 2,000 followers.

Wisdom that she has shared on social media include lessons on sheep and electric fences, how smart animals are, the pitfalls of mating, and being showered in blood when trying to kill livestock.

Chandler’s farming career started when she was given four hens as a wedding gift in 2010. Prior to that, she had spent most of her adult life working in the US Navy, before becoming a tech writer and editor for a defence contractor.

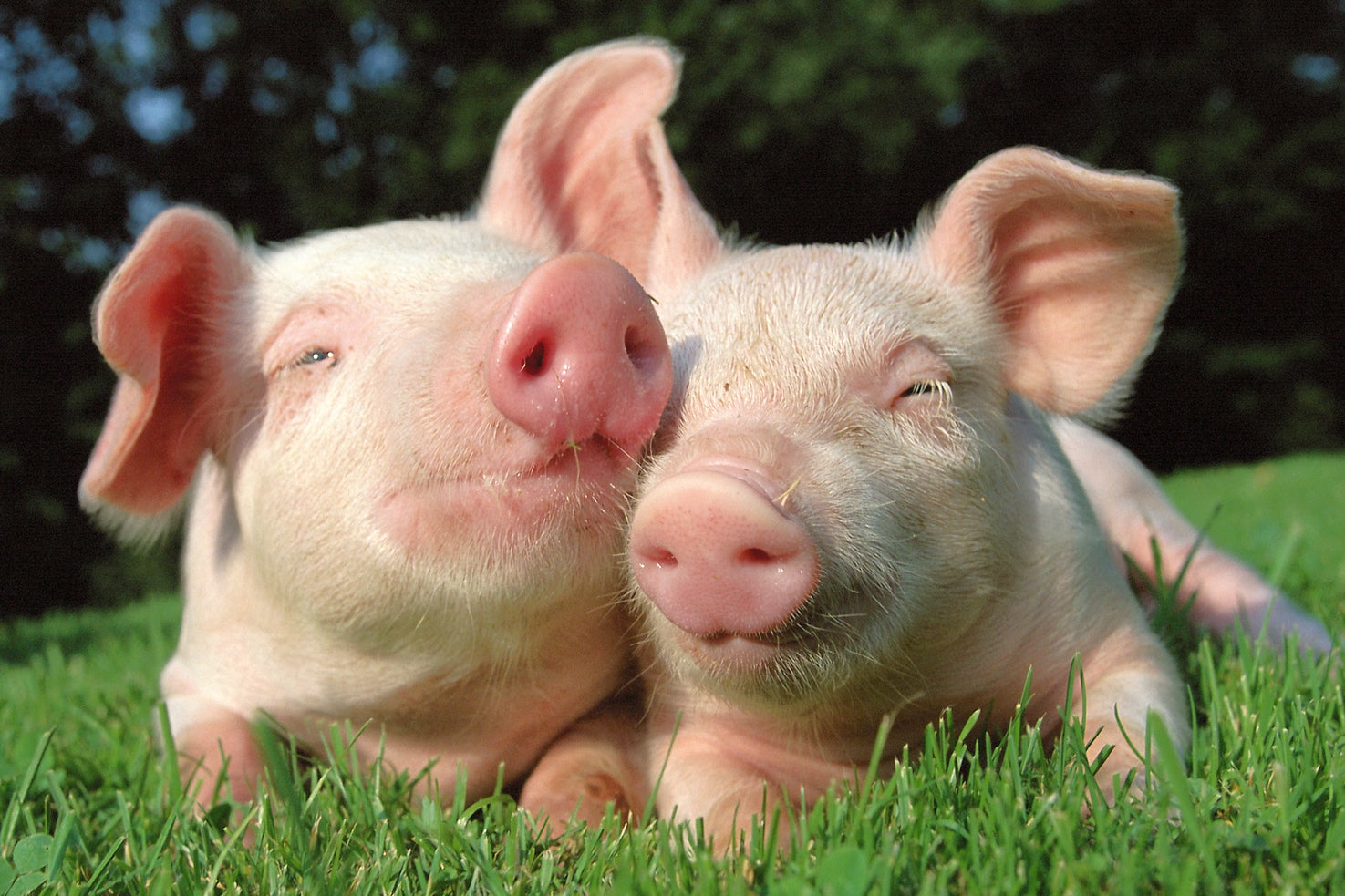

When she was made redundant, she decided to see what she could do with her 2.5acre plot of land where she lives with dogs, cats, rabbits, sheep, pigs, chickens, guinea fowl and a veg patch. Each has a role to play in making the farm, where she lives with her husband, work she says.

“This is how I learned that chickens are a gateway drug, and if you're going to get a few hens you might as well save yourself the trouble and build a barn and go ahead and get larger livestock. The pigs are here to prevent soil compaction and consume the by-products of rabbit slaughter that I don't want, like entrails." The rabbits and sheep, meanwhile, provide meat, fur, and wool.

While the farm isn’t self-sufficient – “fresh tomatoes in the heart of winter are one of modern life's little miracles and I have no intention of giving them up," says Chandler – she is hopes to one day create 75 per cent of what she and her husband eat.

“While 100 per cent self-sufficiency is a grand ideal, it's worth noting two things: one, our ancestors never achieved it as family units, only in community; and two, if our pre-industrial ancestors saw us turning down things like electric heat and cheap salt they'd very justifiably think we were either stupid or crazy.”

Nine lessons Chandler has learned since becoming a farmer

Make friends with vultures.

A ewe with a lamb to defend may be startlingly aggressive. Always work in pairs.

You will not believe how much gross stuff you can handle until you've been farming for a couple years.

Farming will sound like a great idyllic life until January. Or a hurricane.

Once a raccoon figures out it can get into your coop and eat your chickens, it will keep coming back until you don't have any chickens.

Learning to do a good regulation rugby tackle will serve you in good stead when you need to catch a particularly wily goat.

You can get almost anyone to come help you with chores once. If someone comes back more than once they're a gift from God.

Sometimes there will be an individual animal you just can't eat. That's ok. Humans are complex.

Chickens love to dust bathe. If they live in confinement this dust includes their fecal matter. Don't get live chickens near your mouth.

Having farmed for almost a decade, Chandler has left nothing to chance and takes a scientific approach to her work including studying the latest research into the psychology of goats to protect their well-being, organic farming, and the health of livestock.

“The absolutely most important thing I've learned is that none of the livestock have read the books and research. Or if they have, they regard it as a manual for what not to do. In the military the wisdom is 'no battle plan survives contact with the enemy' and in farming no plan will survive contact with your animals.

"'Ah yes,' you will say, 'I will breed my ewes in November and have lambs in April when the weather is mild.' In September you will find your ram mysteriously cavorting amongst the ewes. In February you will be freezing to death in the barn in bitter cold weather waiting for ewes to give birth.”

After spending most of her life in the military or doing contract work, she says she was drawn to farming because it is "life affirming."

"Producing food and sharing it with friends and loved ones are old, old ways to show caring." Livestock farming is by nature tough work, both physically and emotionally, highlighted as Chandler recalls how she became worried when she lost a piglet was bottle-feeding in the autumn.

“I went out to feed everyone and couldn't find him. I walked all over the pen, getting more and more upset, calling him, thinking he'd been taken by a hawk. When my husband came out, I told him I couldn't find the piglet, and he said, 'The piglet right behind you?' Who knows how long he'd been back there, trotting along as I searched for him.”

“The hardest moments are always slaughter days. It gets easier but it never gets easy. My goal is that my animals have wonderful lives and one bad moment. The enormity of taking a life is always there”.

The tongue-in-cheek thrills and spills she shares on Twitter, stresses Chandler, should therefore be taken with a pinch of salt.

“You are often cold, covered with something disgusting, bruised, bored, or some combination thereof. The moments we share are the ones that keep us going when lambs die, when squirrels eat all the seed corn, when a loose dog leaves sheep dead and dying.

“While most of us who share our lives on Twitter or Instagram or what have you make it look fun and heart-warming, farming is honestly closer to a calling than a job."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments