Why were the Victorians so obsessed with graveyards?

They’ve certainly gained a reputation for being a rather gloomy bunch of people, but is it true were fascinated with cemeteries and other death rituals? Serena Trowbridge finds out

The Victorians ritualised death. Black mourning clothes were worn for set periods of time after bereavement, the length of time depending on the relationship. After this, grey or purple would then be worn. Jewellery was made of the hair of the deceased and photographs were taken of the corpse with their family. Curtains in the house were drawn after a death, and the bell and door-knocker muffled.

The Victorian attitude to death was epitomised by the public mourning of Prince Albert in 1861. Queen Victoria’s consolation, besides the Bible, was the reading of Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s ”In Memoriam” (1849), a long poem which explores the undulating patterns of grief. Victoria’s response to the poem exemplifies the Victorian approach to death, in which the dead are mourned and memorialised rather than seen as lost forever. This Christian approach is also reflected in the graveyards of the period.

From 1832 or 1841, cemeteries were constructed around London to cope with the growing problem of the burial of the dead. Cremation was rare and seen as unacceptable, and existing graveyards were overflowing, with coffins often stacked up.

Perhaps the most famous of these London cemeteries is Highgate, opened in 1839. It became the resting place for many famous figures, including the author George Eliot, the poet Christina Rossetti, and members of Dickens’s family.

Another cemetery, at Brookwood in Surrey, was opened in 1854 after the cholera epidemic of 1848-9 overwhelmed the system. It was served by the London Necropolis Railway, which ran trains from Waterloo carrying mourners and coffins. The Necropolis Railway emphasised the class-bound nature of death and mourning, with carriages and waiting rooms (which doubled as funeral parlours) divided into first, second and third class.

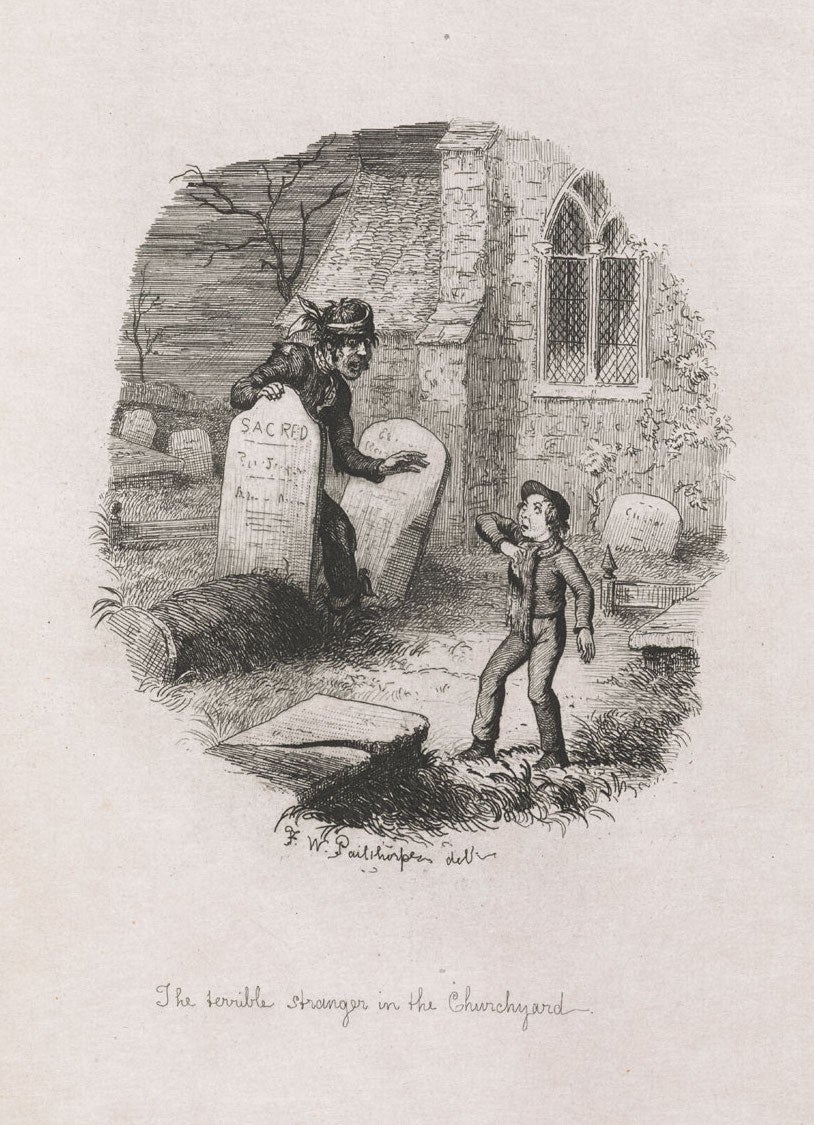

Graveyards offered a sacred space for bereaved families to reflect on their losses. This encounter between the living and the dead provides one of the most famous scenes in Victorian literature, when young orphan Pip visits the graves of his family in the opening pages of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations (1861).

Pip explains how his images of his family were formed by their tombstones: “The shape of the letters on my father’s, gave me an odd idea that he was a square, stout, dark man, with curly black hair. From the character and turn of the inscription, ‘Also Georgiana Wife of the Above’, I drew a childish conclusion that my mother was freckled and sickly.”

The site of the burial of the dead also proves a turning point for Pip’s future. He is surprised by the appearance of “a fearful man”, Magwitch, who demands Pip’s help. The child’s terrified acquiescence alters the course of his life in ways he does not yet fully understand.

This tendency to situate significant encounters among the dead is widespread in Victorian fiction. In The Woman in White (1860) by Wilkie Collins, a key encounter between the hero and the elusive woman in white takes place in a graveyard: “Under the wan wild evening light, that woman and I were met together again, a grave between us, the dead about us, the lonesome hills closing us round on every side.”

The conviction in resurrection and ascension to heaven which sustained the mourners was accompanied by a growing interest in seances and spiritualism

As the hero-narrator points out, “the lifelong interests which might hang suspended on the next chance words” make him anxious and add drama to an already tense scene.

As spaces charged with emotion, then, in which one may reflect on one’s own future as well as past, graveyards provide a fruitful literary backdrop. Thomas Hardy uses this concept regularly, notably in Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891), in which the tombs of the heroine’s supposed ancestors provide uncomfortable settings for several encounters with her past and present, leading to her ultimate downfall.

Death was not an end for the majority of Victorians, but the beginning of a new future. As Tennyson wrote in his poem “Crossing the Bar”: “I hope to see my Pilot face to face/ When I have crost the Bar.”

The conviction in resurrection and ascension to heaven which sustained the mourners was accompanied by a growing interest in seances and spiritualism as a way to remain in contact with the dead, and of course, the graveyard consequently featured in many ghost stories.

Truth is even stranger, however. In 1869, the body of Elizabeth Siddal, painter and poet, was exhumed by firelight in Highgate Cemetery, to recover the manuscripts of poems tossed in with her body by her grieving husband, the Pre-Raphelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti. It was reported that her body was perfectly preserved, and that her red hair had continued growing and filled the coffin.

The worm-eaten manuscripts are now in the British Library, and it has been suggested that Siddal’s exhumation inspired Bram Stoker in his portrayal of Lucy Westenra in Dracula (1897).

Graveyards are a place where different human concerns meet: sadness, loss, history, tragedy, and uncertainty for the future. Yet these fictional graveyard encounters contain seeds of hope, in which the characters move from loss to a brighter future.

Serena Trowbridge is a reader in Victorian literature at Birmingham City University. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks