Valentine’s Day: The devastating love story of Camila O'Gorman

Argentine socialite executed by order of ruthless 19th-century dictator for forbidden affair with Jesuit priest

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Camila O’Gorman was just 20 years old and eight months pregnant when she was executed by a firing squad in the courtyard of Santos Lugares Prison in Argentina on 18 August 1848.

Alongside her, likewise bound and blindfolded in a wooden chair, sat a 24-year-old Jesuit priest, Father Ladislao Gutierrez, doomed to share the same fate.

Their crime? To have fallen in love.

Camila was the granddaughter of Irish merchant Thomas O’Gorman, a native of County Clare who had cast aside the anti-Catholic persecution of his homeland to serve overseas in the French army, later pressing on to South America where he made his fortune.

In Mauritius, he had married Marie-Anne Perichon de Vandeuil, the daughter of a French colonial administrator. She who would become an influential presence in Buenos Aires, the couple’s home the centre of the Argentine capital’s social whirl, hosting Spanish dignitaries, wealthy business owners and diplomats.

She would also court scandal, engaging in an affair with Santiago de Liniers, Count of Buenos Aires, who defended the city from British invasion in 1806 and 1807 and was rewarded for his heroism by being named Viceroy of the Rio de la Plata.

Another of her lovers was James Florence Bourke, a former comrade of O’Gorman’s now spying for Britain and exploiting her connections to report back to London on anti-Spanish resistance.

These intrigues would foreshadow the tragedy to befall Marie-Anne’s granddaughter.

Camila was born in 1828, the fifth of six children born to the son of Thomas and Marie-Anne, Adolfo O’Gorman y Perichon Vandeuil, and his wife Joaquina Ximenez Pinto. One of Camila’s siblings would join the Jesuit Order, another would found the Buenos Aires Police Academy.

General Juan Manuel de Rosas had seized control of Argentina in 1835 and ruled with absolute power, torturing dissenters who spoke out against him.

Camila, as a close friend of Rosas’s daughter Manuelita, was a regular visitor at the Governor’s Residence in her teens and was approved of as a respected confidant.

Until, that is, she was introduced to Father Gutierrez, a friend of her brother’s from seminary. The Jesuits were disapproved of by General Rosas for their outspoken criticism of his draconian rule. He would later banish the Catholic society from Argentina altogether.

Gutierrez had been assigned as parish priest to the O’Gorman’s local church, Our Lady of Relief, and visited Camila regularly, beginning a clandestine romance.

Aware of the hostility to their union, the couple eloped on 12 December 1847, fleeing to the town of Goya in Corrientes under the protection of the province’s governor Benjamin Virasoro, long hostile to Rosas. Here, they established a school and lived under assumed names, enjoying the happiest days of their short lives.

Camila’s father Adolfo O’Gorman, a stern disciplinarian, meanwhile wrote to Rosas protesting the family’s horror at the development and said Ladislao had “seduced her under the guise of religion, and stole her away abandoning the parish on the twelfth of this month”.

Speculating they would cross into Bolivia, O’Gorman implored: “Senor, I beg your excellency to send orders in every direction to prevent this poor wretch from finding herself reduced to despair... understanding that she is lost, she may rush headlong into infamy.”

The elopement became a matter of public concern when the Rosas opponent Domingo Faustino Sarmineto, exiled in Uruguay, accused the dictator of allowing the moral corruption of Argentina’s women to fester, forcing his hand. Rosas himself was known to have fathered five children by a maid, Maria Eugenia, making the hypocrisy of his stance all the more acute.

“Exemplary punishment” was meanwhile demanded for Camila’s having brought the good name of the country’s immigrant population into disrepute, not least from the girl’s own father and from Father Anthony Fahy, chaplain to Argentina’s Irish Catholics.

After being recognised and denounced by one Father Michael Gannon on the streets of Goya, Camila and Ladislao were abducted and dispatched to prison at Santos Lugares. Camila sought help from Manuelita Rosas, who furnished her cell with a piano and books but could do no more due to the forcefulness of her father’s conviction, the dictator determined to make an example of them in response to the very public nature of the criticism he had received.

Condemned to death with the endorsement of lawyer Dalmacio Velez Sarsfield, Camila was visited by the prison chaplain who baptised her unborn baby, the mother drinking holy water while consecrated ashes were applied to her forehead so that at least the child might ascend to heaven.

The next morning, she and Ladislao were executed by musket fire and buried together in a single coffin, the only act of compassion they were granted at the instigation of Rosas’s secretary, Antonio Reyes, who could not bear to witness the shooting.

The condemned lovers have been remembered ever since for the intensity of their passion and for the senseless brutality of their end.

Such was the revulsion to their killing, Rosas lost support and his enemies were emboldened. He was finally overthrown after being defeated at the Battle of Caseros by General Justo Jose de Urquiza in 1852 and escaped to Britain, where he lived out the last 25 years of his life in Southampton.

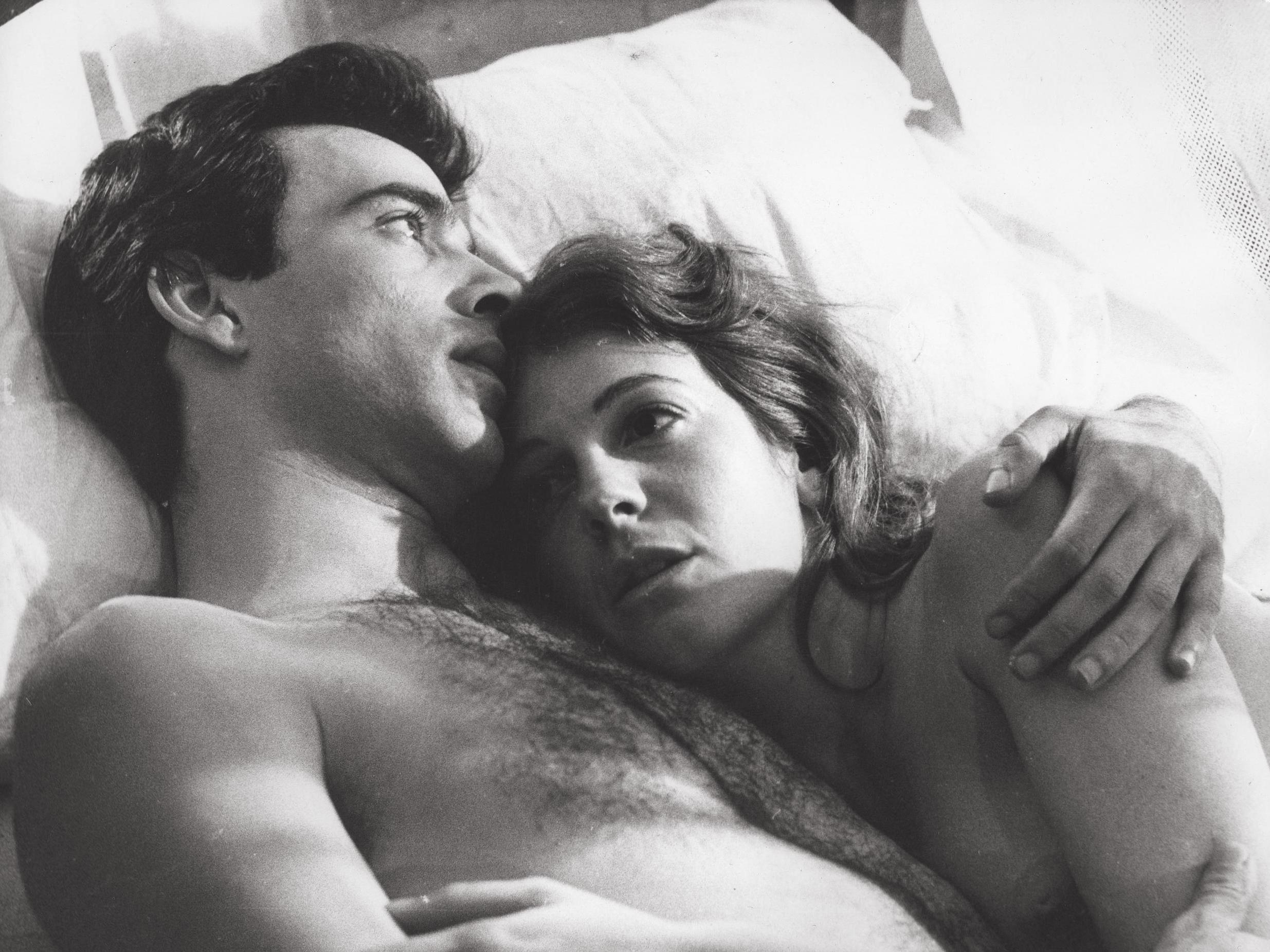

Maria Luisa Bemberg adapted this tragic tale into the Oscar-nominated film Camila in 1984, starring Susu Pecoraro and Imanol Arias.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments