Sofie Hagen hadn’t slept with anyone in 3,000 days – and wanted to know why

The comedian and author was inundated with responses after they asked people why they weren’t having sex. They’ve now written a book on what they learned, both about an epidemic of celibacy, and their own relationship to sexuality. They speak to Cathy Reay

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last year, roughly 3,000 days after they last had sex, the comedian and author Sofie Hagen published a questionnaire online. “If you do not have sex, but you wish you were, why do you think that is?” it asked. “I literally thought I was going to get maybe 30 replies,” Hagen says today. “I really thought I was so alone; I didn’t think anyone else had issues like this.”

It turned out they weren’t alone at all. Overwhelmed by the number of responses, they had to shut the link down within two days. Today, they are speaking to me via Zoom, where, despite the nature of our conversation being personal and potentially sensitive, Hagen, who was born in Denmark but now lives in London, is warm, bubbly and open. “I had this idea that I was going to go on this journey to find the solution,” they tell me, excitedly. “I couldn’t possibly imagine a happy ending that didn’t involve me having sex.”

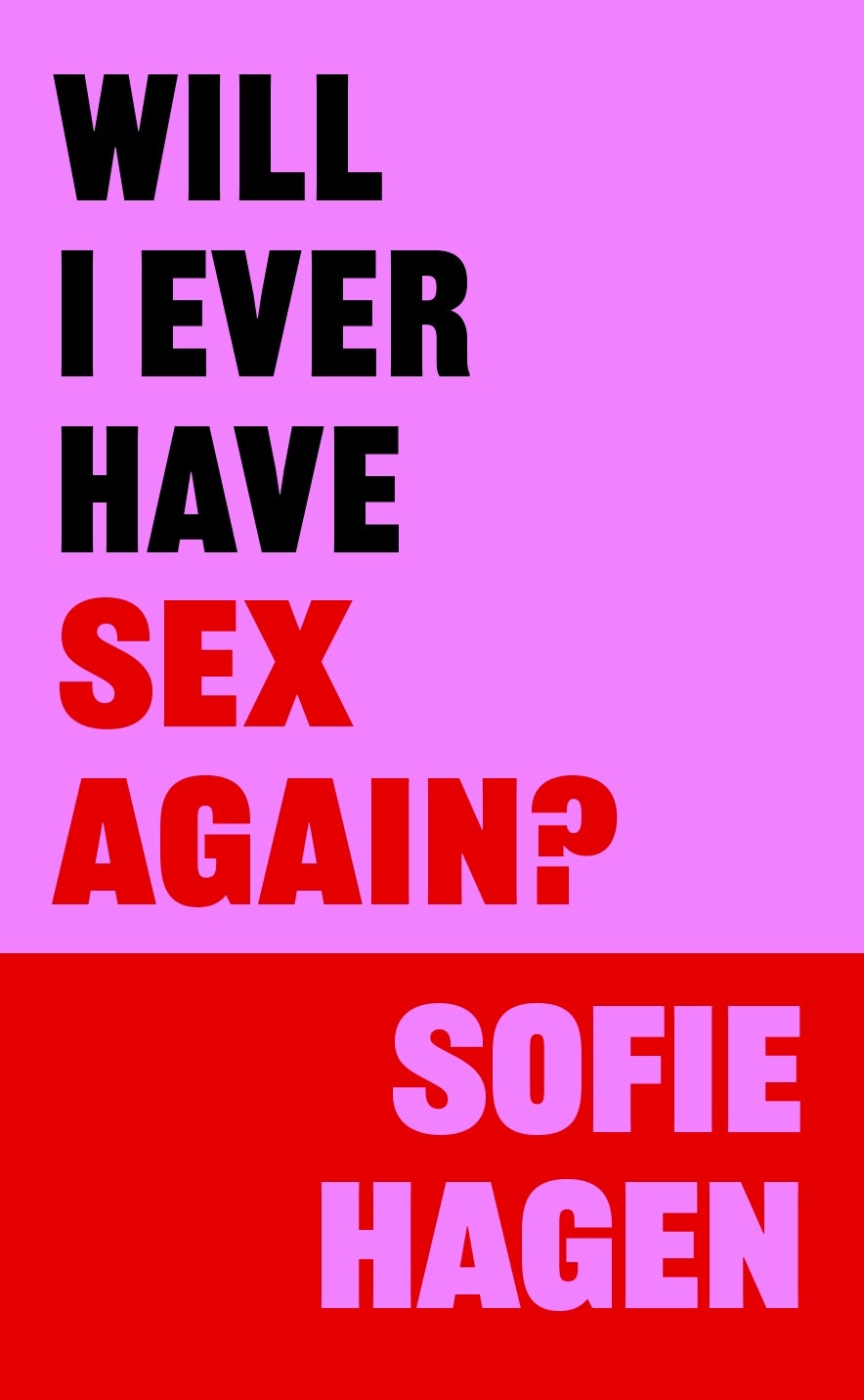

And so they wrote Will I Ever Have Sex Again? – a guide to how societal norms have shaped our understanding and experiences of sex, and sometimes prevented us from having it. Hagen writes largely of their own experiences, but also pulls from the experiences of those who responded to their survey, along with the opinions of experts. They hadn’t realised the extent of some of the things that stop us from having sex. Some people become parents, others move back in with family after years of being away, many more are navigating the cost-of-living crisis – all have the power to completely kill the libido.

Hagen also describes barriers to sex that hit far closer to home. The first chapter of their book opens with their account of a long-term relationship they had with a man who was already in a relationship. He kept his affair with Hagen a secret from his other partner for years. Despite the length of the relationship and its intensity, he and Hagen never had sex – in fact they rarely even touched. Nevertheless, the experience massively affected Hagen’s ability to connect with others afterwards. Hagen’s account of his gaslighting and narcissism, coupled with the hope Hagen felt that the relationship would improve over time, makes for a sobering read, and one that sadly many people will relate to.

“One of the reasons narcissistic relationships work is because we don’t tell people [about them],” explains Hagen. “We don’t say it out loud, whether that’s because we’re not allowed to, or we feel ashamed to.”

While narcissistic behaviour can be exhibited by anyone, a study published by the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology in 2023 showed that men score higher in narcissism than women*. Men are also, by way of patriarchy and sexism, often the dominant authority in the bedroom. Generally in mutually consenting ways – sometimes not. And if nobody is talking about the times we don’t consent – and therefore fail to realise how common this dynamic really is – the cycle of self-blame is perpetuated.

Writing this book I realised, oh, I can learn to love my body in the confines of my own home, my own safety, and I do. But it’s such a long way from that to believing that other people would

It was important to Hagen that they acknowledge the things they might’ve done wrong in their relationships, too. They were inspired by Why Did You Stay? a memoir by the actor Rebecca Humphries, which detailed the breakdown of her relationship with the comedian Seann Walsh. “She wrote it in such a beautiful, non-aggressive way,” Hagen says. Their own book follows suit, Hagen writing of their experiences with similar compassion, recognising that many of the men they’ve slept with are “actually nice people” and might not have been aware of their narcissistic traits.

Once you’ve experienced sexual or intimacy trauma, it can be incredibly difficult to feel safe in those contexts again. In their book, Hagen describes what they term “the four stages of ‘no’.” One is “you have to trust your ability to feel if you want sex”. Two is “you have to trust your ability to say no.” Three is “you have to trust that your partner can hear or interpret your no”. Four: “You have to trust that they will stop if you say no.”

This all makes sense, I tell Hagen, but I wonder how often people actually feel able to talk through any of this with the people they want to have sex with. If we look at sex in films or on TV, characters rarely talk – they just take their clothes off and get on with it. What we learned in school – at least when Hagen, who was born in 1988, and I were young – didn’t include how to talk about having sex. “What I learned about sex was incredibly toxic and often wrong, but at least it was a script,” Hagen recalls. “How do we navigate this stuff without a script, though?”. It can feel awkward and vulnerable to articulate our needs in the bedroom if we don’t know what to say.

“We’re not even questioned [by men] as to whether we have preferences,” says Hagen, who attributes this back to the somewhat mechanical perspective offered by mainstream sex education. “Women’s magazines and porn would tell us ‘the g-spot is there, so you should want this position’,” they say, remembering that this was the only facet of sex they were encouraged to talk about. “It was always: what’s your favourite position? How many can you do?”

“That’s great,” they add, “but if there’s no chat about our preferences beforehand, how can we determine whether this journey we’re going on is something we both want? You need communication first. You don’t know me. You don’t know what I like. You don’t know what’s triggering to me. You don’t know which parts of my body respond to what.”

“How many of us are truly confident or comfortable saying, ‘I like or don’t like this’,” they ask. Not very many, I guess. And a lot of that is down to safety, safety to express our true thoughts, concerns and feelings. Hagen comes back to this a lot in their book. How safe do we really feel in moments of intimacy, and what about these moments is causing us to feel potentially unsafe?

Aside from sexism, other systems of oppression, such as racism, ableism, fatphobia and transphobia, all factor into how comfortable we are having sex with other people. In the book, Hagen talks about how the politicisation of their body and the fact that it doesn’t conform to westernised beauty standards, such as being slim and ultra feminine, are barriers to sex. “Writing this book I realised, oh, I can learn to love my body in the confines of my own home, my own safety, and I do. But it’s such a long way from that to believing that other people would. How could people love my body when they’ve watched the same [media] I’ve watched, and I’ve barely managed to love myself?” they ask.

“I think we’re so often gaslit, right? ‘No, no. You’re beautiful! Don’t say that about yourself.’ But westernised beauty standards exist, and maybe you think I’m beautiful, but please acknowledge that we all know that the world doesn’t think that.”

When you have a body that is at greater risk of someone saying something hurtful at any time, relaxing into intimacy can be challenging. “That’s one of the things that kept me from [having sex] – my brain going, ‘oh, but it could be dangerous, don’t do it’. Sometimes you have to take that risk and that’s scary. But it also has to be a truth that there are people out there who would like to have sex with you, and they might be harder to find, but they are there. And if you want sex, you have to take a little risk.”

When they began writing Will I Ever Have Sex Again? Hagen set out to find the “solution” to why they weren’t having sex – and, in the process, have lots of sex. But it didn’t quite pan out as they anticipated. Instead, their journey proved to be far richer, and one that taught them much about themselves, their relationships and the world we live in. Which is surely an essential foundation of great sex, anyway.

“At the end of the book, I am sitting in my living room with my dog drinking hot chocolate and I am in the very beginning stages of flirtation with a fellow non-binary person,” says Hagen. “And my focus is on safety, community, exploration, curiosity and healing.” This feels a far cry from the narcissistic relationships of their past. “I’m taking it slow, getting to know myself and them, learning how to set boundaries and state my needs.”

Will they ever have sex again? Who knows? But it sounds like they got their happy ending regardless.

‘Will I Ever Have Sex Again?’ by Sofie Hagen is in shops now