I’d love a robot nanny for my children – as long as it didn’t love them back

The PM suggested that nearly 40 per cent of jobs could be affected by a future boom in robots and artificial intelligence. It got Charlotte Cripps pondering her childcare arrangements, and what life could look like with a cyborg childminder in tow

Rishi Sunak has got me thinking about robots. In his pre-election speech, the PM suggested that while artificial intelligence can be dangerous, it can also provide opportunity for progress – so much, he claimed, that its effects could be even more significant than the industrial revolution. But what would these effects look like in the home? Could these robots help with the housework? Or help me look after my children? Sunak suggested that AI is set to affect nearly 40 per cent of jobs – is being a nanny one of them?

I pondered how an AI robot nanny might be advertised. “Are you tired of the endless search for a reliable, trustworthy and engaging childminder? Look no further! The solution to all your childcare needs is... an AI robot nanny.” To be honest, I didn’t mind the idea. There’s the unwavering reliability, no more last-minute cancellations, or unexpected days off. They could be available around the clock, wouldn’t get tired or fed up with your kids, and could probably load the dishwasher and fold the laundry, too – leaving us parents more time to spend with our children. The only big drawback? They lack emotional connection.

Never mind, I think to myself, as I imagine the perks of a future with AI nannies. My children get love from me – I just need backup support. I’m a single mum with a six- and eight-year-old, and quite frankly, the idea of a robot nanny on tap is an absolute dream. I know, of course, that there are ethical concerns. As Nick Hawes, professor of AI and robotics in the Department of Engineering Science at Oxford University, points out: “Who is responsible if you leave your child with a robot and something goes wrong?” I hadn’t thought of that…

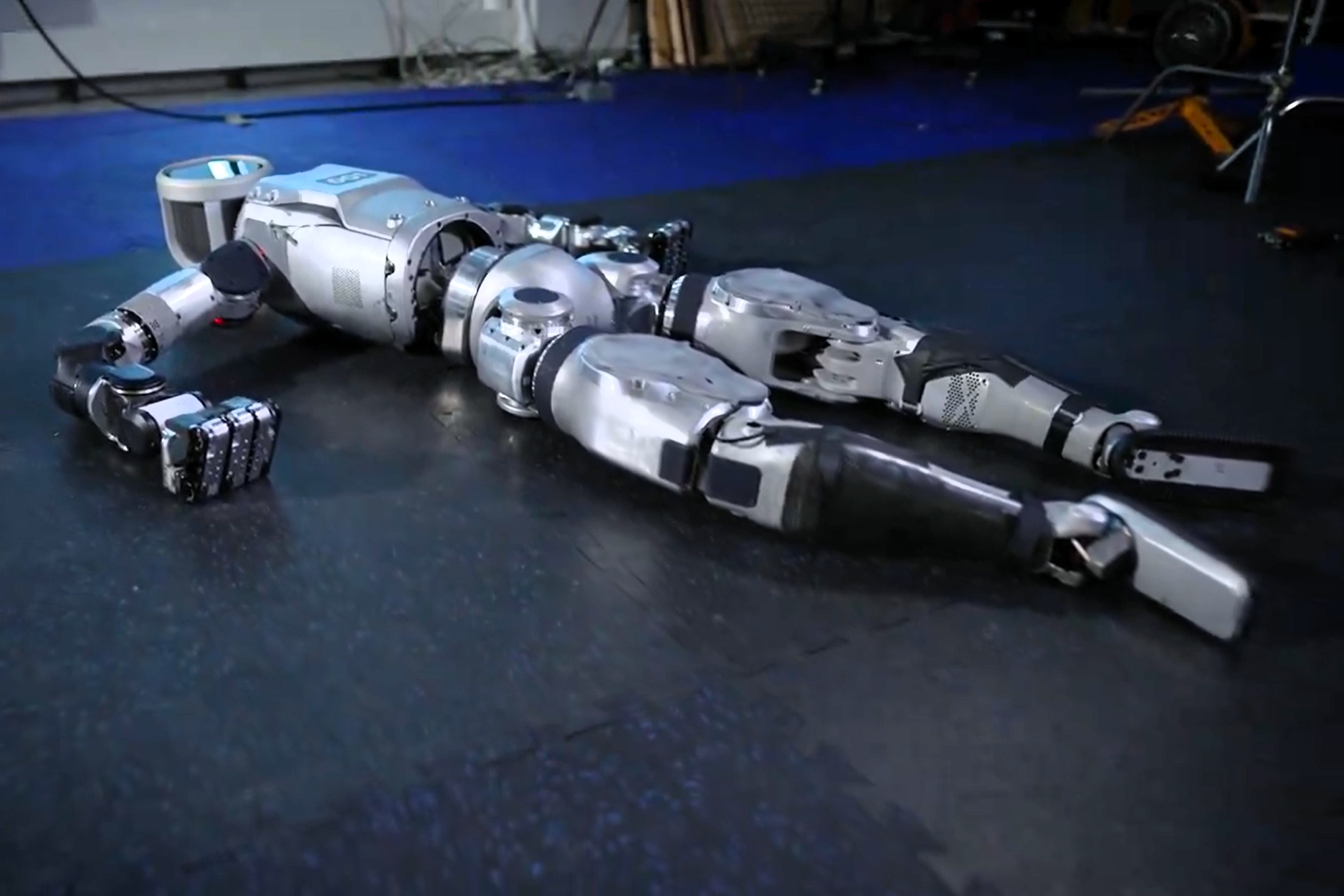

Hawes tells me that a robot nanny is “possible – but it’s a long way off. Maybe five or 10 years.” There is huge interest and a lot of money currently going into building humanoid robots, he adds. However, the autonomy and intelligence of these machines is still very limited. “There are demos of robots loading a dishwasher and maybe moving some items around on surfaces – and that is really state of the art,” he tells me. “[But] it’s going to be a very long way until technology can do emotional intelligence as well as a human.”

Presumably, an AI robot would be a one-off purchase. Or do you rent them? What could a nanny robot look like, I wonder? “Beyond a humanoid shape,” Hawes says, “who knows? Maybe it’s got four legs, rather than two. Maybe it’s got six legs. I don’t know. As a parent, I also want 10 arms and more cameras.”

Maybe I’ve been watching too much Black Mirror, but the idea of robots living among us doesn’t feel like such a big leap of the imagination for me. I’ve seen the footage of Ai-Da (pronounced Ada), a realistic robot artist created and built in the UK, who makes art and poetry and “talked” to the House of Lords in 2022. She had a black bob, orange shirt and grey dungarees – even a dimple on her chin and a strangely ethereal voice.

The cybersecurity aspects are terrifying. If you get out of the shower and walk past a robot nanny with a towel on, is the robot recording that? Is that being streamed to the cloud?

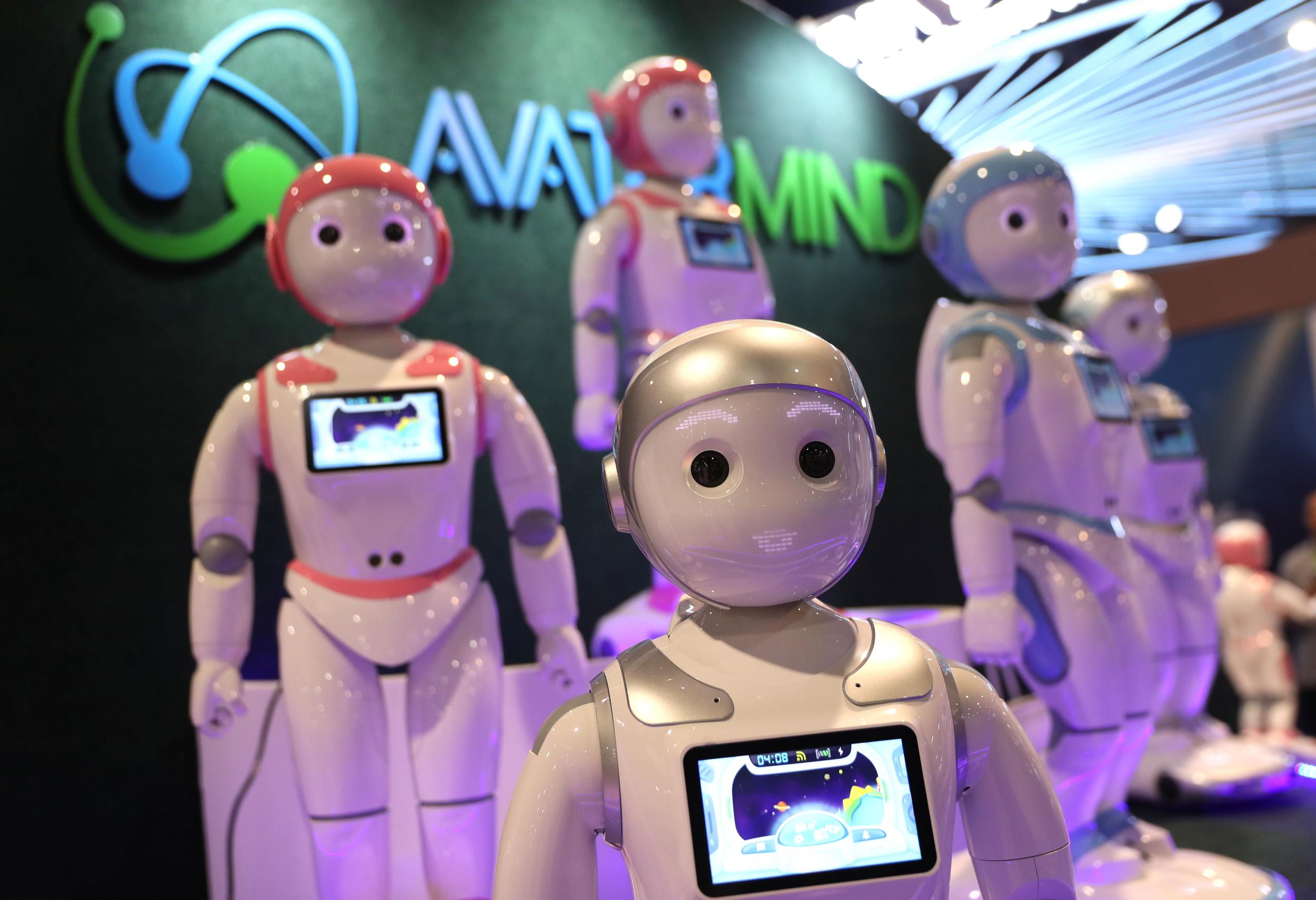

For anything more complex, though, there’s nothing on the market yet for parents. There are robots that can sing and dance and tell bedtime stories, and robots that can monitor your blood pressure and learn the floorplans of your home so they can move between rooms and hand things to you. But none of these creations is yet up to scratch for a job as a nanny, says Dr Emmanuel Senft, a research scientist at Switzerland’s Idiap Research Institute and the head of its Human-centered Robotics and AI group.

“If we want a robot doing the simplest job of a nanny, for example, checking that a child is sleeping or notifying the parents if the child is crying, we are probably already there or very close, and actually a simple camera can be enough,” says Senft. “But if we want a robot that can cook, load a dishwasher, provide children with core values and help them to develop themselves appropriately, then we are pretty far off, and might never reach it.”

He admits he might be “surprised by progress” in the coming years, though. “It’s often said that what can be easy for a human can be very hard for a machine, and what can be hard for a human can be very easy for a machine,” he says. “For example, we only managed recently to [get a robot to] detect automatically a bird in a picture; it’s called computer vision. But finding the solution to complex calculations is very easy for a robot.”

The main challenge for creating a robot nanny, though, is that it is very hard to create one model with all the developed aspects available: mobility, perception, expression and manipulation. “There are very good robots in each of these categories, for example, Atlas from Boston Dynamics has very impressive mobility,” he says about the robot that is able to run, jump and execute the perfect backflip. “Similarly, the Ameca robot from Engineered Arts is very expressive. It has a face able to generate expressions. However, these capabilities are still challenging on their own, and having a robot being good in all areas is even harder.”

Getting a robot to look human is also tricky. “If the robot is even slightly off, it can feel icky for the humans around it,” he says. “This effect [in robotics] is termed the ‘uncanny valley’.” Cost is still a major hurdle, too. “The more complex, the more tasks and the harder it is and more expensive.”

But more importantly, he adds, do we really want a society with robot nannies taking care of our children’s education and development? “Personally, I think that robots could help but they should not be planned to replace humans and that’s my opinion on robots in general, they should be there to augment humans, not replace them,” he says. “Children need social interactions for healthy development, I don’t think we should rely fully on robots to provide them.”

While Senft believes that parents should have the freedom to decide how they want their children to interact with AI, it must “support healthy development”. Likewise, Hayes questions the benefits of a robot nanny – both in terms of security and on an emotional level. “You have to understand the technology that is in your home – it’s equally true when you give your kids a phone and you let them install apps on it,” he says. “The cybersecurity aspects are terrifying. If you get out of the shower and walk past a robot nanny with a towel on, is the robot recording that? Is that being streamed to the cloud?”

Researchers have been expressing concerns about robot nannies for years. In Noel and Amanda Sharkey’s 2010 paper “The Crying Shame of Robot Nannies: An Ethical Appraisal”, they raise questions about “human rights, privacy, robot use of restraint, deception of children and accountability”. The most “pressing” ethical issue they look at is the impact on the psychological and emotional wellbeing of children – citing “cognitive and linguistic impairment” as well as attachment disorders.

I’d definitely pull the plug on the nanny if my kids started to feel love for it, when clearly it couldn’t be reciprocated. But these researchers have also found that “occasional use” of a machine may be no more harmful than watching TV or using an iPad for a few hours, especially if the child is securely attached to their primary carer.

While it seems my dream of an AI nanny will come true, it might, however, be too late. My children might have grown up and got over the intense nanny phase. But, as Hawes says: “It might not benefit us as parents, but these robots will be looking after us in our old age.”

While it seems the idea of an AI nanny will one day become reality, it might be too late for my own needs. My children will likely have grown up and got over the intense nanny phase by then. When I’m a grandmother, though, things could get interesting. Will my grandchildren need me beyond an occasional cuddle because the robot’s taken care of everything else? Will I worry – as all grandmas do – that my precious little ones are in danger from a robot gone rogue? All questions for another day. But for now, I’d do just about anything to have an AI nanny at my disposal. As long as my kids understand that it’s not the genuine article, and incomparable to humanity – it’s just metal and wires and a helping hand.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks