Why it’s sometimes good to steal from other musicians

Stealing is bad, right? Well, not always, music and other forms of art have a long tradition of stealing, and it has often produced some great, unique works, writes Ross Cole

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

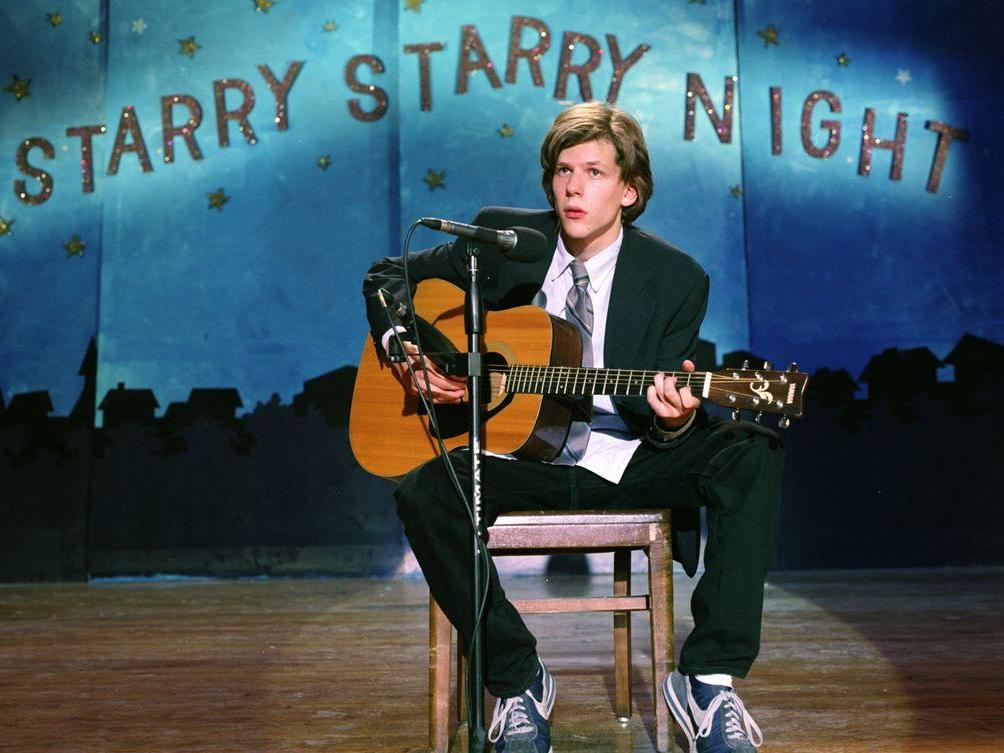

Your support makes all the difference.In Noah Baumbach’s semi-autobiographical film The Squid and the Whale, the young protagonist Walt performs a song at a school talent show that he claims to have written himself. He wins first prize, his girlfriend loves it, and at dinner his overbearing dad says that it reminds him of his second novel.

But of course Walt gets found out. He didn’t write it, Roger Waters did. It’s the song “Hey You” from Pink Floyd’s 1979 album The Wall. Confronted by the school therapist, Walt concedes: “I felt I could have written it … so the fact that it was already written was kind of a technicality.”

It’s something most of us have felt before. Plagiarism as an assertion of identity, a misguided sense that we own the things we love. The composer Igor Stravinsky once referred to this affliction as “a rare form of kleptomania” – plundering of the musical past as raw material for the present.

Stravinsky was doing something quite different to Walt. He refashioned his stolen sources into something new: Russian folk melodies were incorporated into The Rite of Spring and material from the classical era gave rise to Pulcinella. And yet Stravinsky tells us that Pulcinella was not only the first of his “many love affairs” with the past, but also “a look in the mirror”. Just like Walt, then, Stravinsky’s plagiarism was a form of deferred and narcissistic self-recognition.

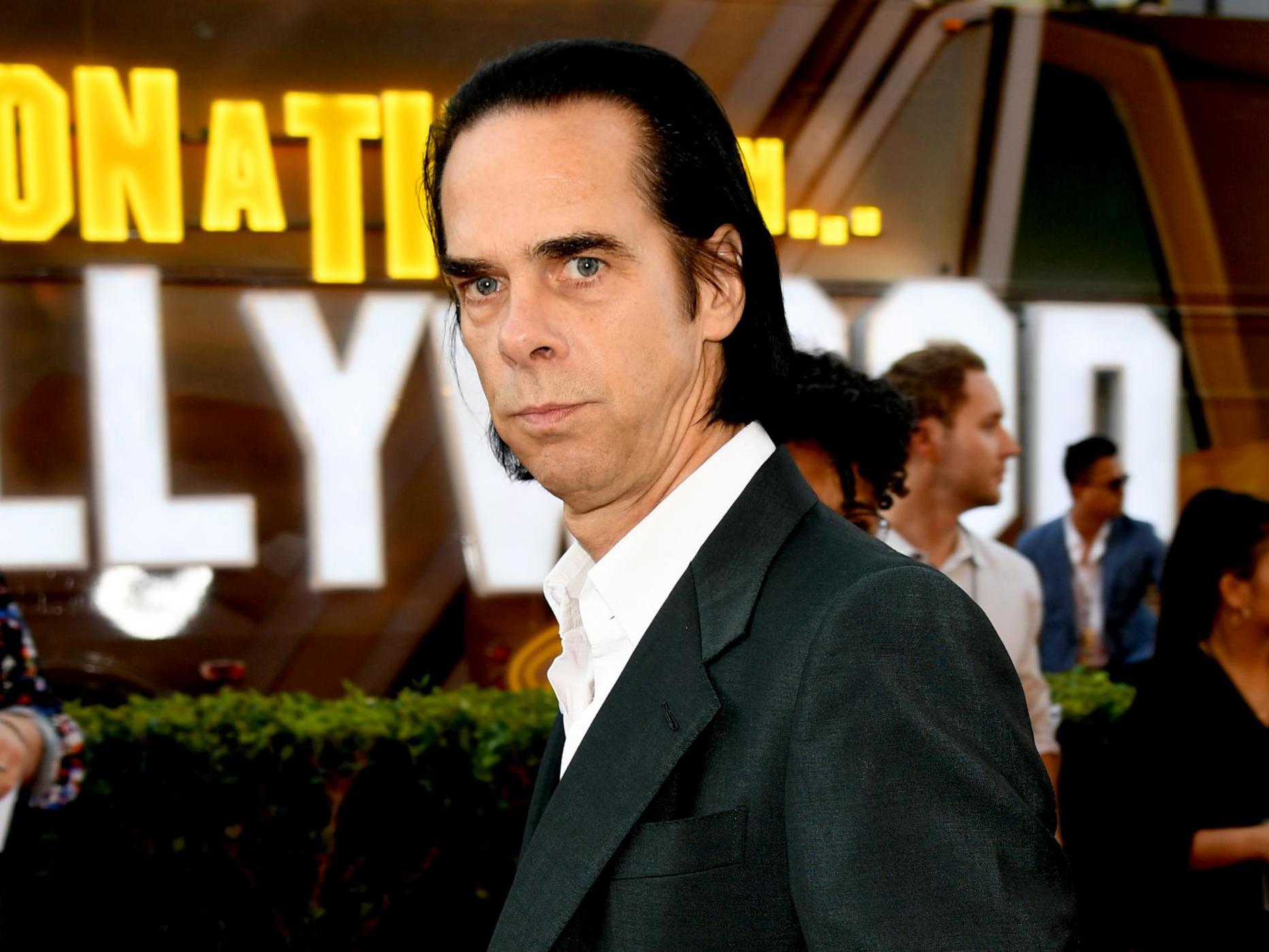

We can look at such acts in one of two ways: either as an unethical infringement of somebody else’s intellectual property or as the symptom of an attitude that underpins creative endeavour across the arts. In one of his Red Hand Files bulletins, the singer-songwriter Nick Cave urges us to embrace the second of these:

The great beauty of contemporary music, and what gives it its edge and vitality, is its devil-may-care attitude towards appropriation – everybody is grabbing stuff from everybody else, all the time. It’s a feeding frenzy of borrowed ideas that goes towards the advancement of rock music – the great artistic experiment of our era.

“Plagiarism”, he writes, “is an ugly word for what, in rock and roll, is a natural and necessary – even admirable – tendency, and that is to steal.” We could tell the history of rock as a twisted genealogy of theft, beginning with Elvis’s debut single – a cover of Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s ”That’s All Right (Mama)” in 1954.

Cave likewise treads in Elvis’s footsteps with his 1985 album The Firstborn Is Dead. It features tracks such as “Tupelo”, a paraphrase of John Lee Hooker’s spine-chilling “Tupelo Blues”; and “Blind Lemon Jefferson”, a homage to a blues singer of the same name. These singers had, in turn, written their songs by drawing on a shared tradition of stock or “floating” verses native to the deep south.

No doubt we’ve all come across the following quote, variously attributed to Picasso, Stravinsky, William Faulkner, and Steve Jobs: ‘Good artists copy, great artists steal’

The further back you look, the more such hybridity and assimilation comes to the fore. The blues itself, as Africanists such as Gerhard Kubik have noted, emerges from a complex and centuries-old process of creative interplay between the Arab-Islamic world of north Africa and musical cultures of the Sudanic belt, displaced through Atlantic slavery.

Of course, Walt’s performance of “Hey You” would not fit within Cave’s vision of stealing as “the engine of progress”. For Cave, acts of theft are absolved or justified only if the stolen thing is advanced in some way and made yet more covetable. Elvis, in this reading, is effectively pardoned for his appropriation of “That’s All Right” to the extent that his white-skinned version of the blues (white-washed as rock’n’roll) was an act of “mutating and transforming” the genre that sparked a new mass cultural form still very much alive today.

Another reading, however, is possible: that this new mode of expression was yet another instance of a dominant culture taking “everything but the burden” from African Americans – a longstanding relationship characterised, as the historian of blackface minstrelsy Eric Lott memorably put it, by “love and theft”.

But what Cave is really referring to is a trope central to the literary critic Harold Bloom’s theory of the “anxiety of influence”. No doubt we’ve all come across the following quote, variously attributed to Picasso, Stravinsky, William Faulkner, and Steve Jobs: “Good artists copy, great artists steal”. It seems to have emerged during the late 19th century, but was most famously expressed by TS Eliot in 1920 as “immature poets imitate; mature poets steal”.

Borrowing, Eliot notes, is perfectly normal – what distinguishes bad thieves from good ones is that the former “deface what they take”, whereas the latter “make it into something better, or at least something different”. In the right hands, Eliot is saying, plagiarism can lead to the creation of “unique” works rather than mere hackneyed replication. This modernist dictum chimes with Cave’s claim that artistic crooks must “further the idea, or be damned”.

So is it ever possible to be original? The lazy answer is no. A better answer is that originality is always a scandalous collaboration with the past.

Ross Cole is a research fellow of Music and Politics at the University of Cambridge. This article first appeared on The Conversation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments