There may be a third pillar of physical fitness beyond diet and exercise

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Most of us know that to be healthy, we need to eat well and exercise.

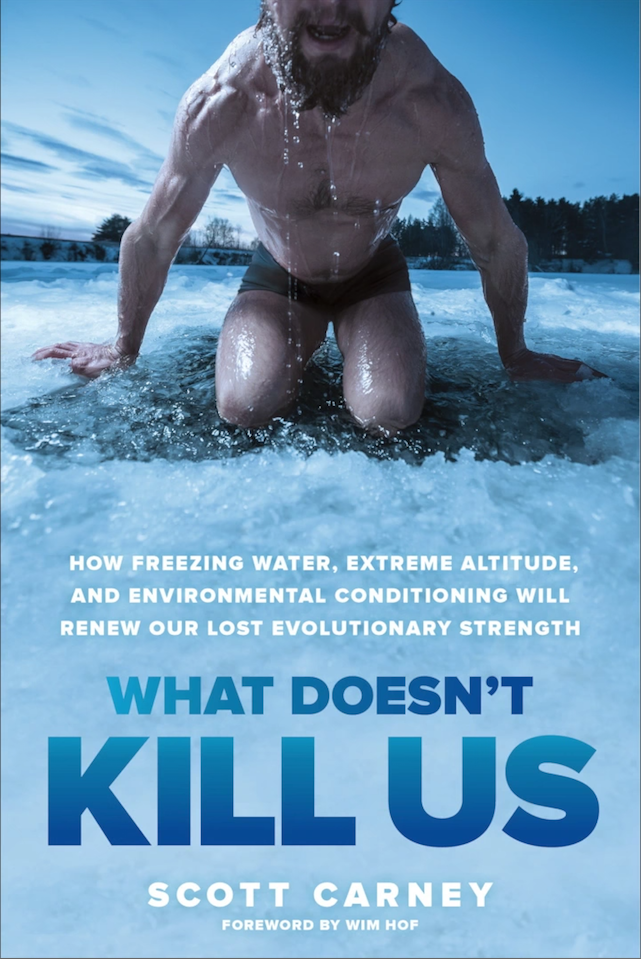

But focusing on just those two things may not be enough, according to a theory investigated (and experienced) by journalist and anthropologist Scott Carney in his recent book "What Doesn't Kill Us: How Freezing Water, Extreme Altitude, and Environmental Conditioning Will Renew Our Lost Evolutionary Strength."

This theory suggests that along with diet and exercise, our bodies might need environmental stress — like exposure to cold and hot temperatures — if we're to reach our full potential. Humans had no air conditioning or heating to help protect us from extreme conditions for most of our existence, after all.

The logic behind this idea is similar to explanations for why we need to eat healthy food and work out. Nature is brutal, and we have evolved to survive in a harsh world, but now modern technology shields us from those physical challenges.

We're built to move and run; being sedentary leads to higher incidences of heart disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes — many of the most common causes of death in the modern world.

And our bodies thrive when we eat natural foods similar to what we'd be able to grow and find in the wild; they experience negative consequences when we consume too many processed materials. We seek out sugar and fat because of their high caloric content, but those foods have become so accessible that we're eating in more unhealthy ways.

The idea behind environmental conditioning is the same, as Carney describes it:

"Anatomically modern humans have lived on the planet for almost 200,000 years. That means your office-mate who sits on a rolling chair behind fluorescent lights all day has pretty much the same basic body as the prehistoric caveman who made spear points out of flint to hunt antelope. To get from there to here humans faced countless challenges as we fled predators, froze in snowstorms, sought shelter from the rain, hunted and gathered our food, and continued breathing despite suffocating heat. Until very recently there was never time a when comfort could be taken for granted — there was always a balance between the effort we expended and the downtime we earned. For the bulk of that time we managed these feats without even a shred of what anyone today would consider modern technology. Instead, we had to be strong to survive."

And though our newfound ability to live in comfort is pleasurable, Carney thinks it may not be healthy.

"With no challenge to overcome, frontier to press, or threat to flee from, the humans of this millennium are overstuffed, overheated, and understimulated," he wrote.

There are some important caveats to that opinion, of course. Modern technology helps us avoid freezing to death in winter and allows us to remain productive through the hottest days of summer.

But there are others who think that many of our current struggles with physical and mental health have to do with the ease of modern life. Anxiety, for example, is one of the most common mental-health issues people face now, but some researchers think it may be an evolutionary adaptation that has gone out of control. Anxiety can be part of our "fight or flight" response, which helps keep us alive in dangerous situations, but because we no longer fear predators and other threats, it can kick in when we have to give a speech or ask someone out.

In his book, Carney investigates the idea that incorporating some environmental challenges back into our lives could lead to health benefits. He embarks on a journey to see if "environmental conditioning" — guided by Wim Hof, a Dutchman who goes by the nickname "Iceman" — can help him unlock new levels of fitness.

Hof advocates (and practices) a method of physical transformation that combines environmental exposure, mostly in the cold, with conscious breathing techniques to try to gain more control over naturally involuntary physical reactions. He claims that doing so can not only strengthen the body in ways that go beyond what exercise can achieve, but also help people heal from injuries and diseases.

It's hard to know how much to buy into Hof's theory. On the one hand, it's appealing to those of us who believe that an almost always comfortable life is probably not physically challenging enough. And it does seem to have some observed health benefits — Carney relates a series of anecdotes in which students of Hof's method experience relief from injuries or symptoms of Parkinson's disease and Crohn's disease. Some scientific studies have independently verified a few claims Hof makes, including that a method of cold immersion and conscious breathing can give people some ability to voluntarily activate or suppress their immune system.

At the same time, it's possible that all or some of the pain and symptom relief that Hof's trainees have experienced is due to the placebo effect — something Carney readily acknowledges.

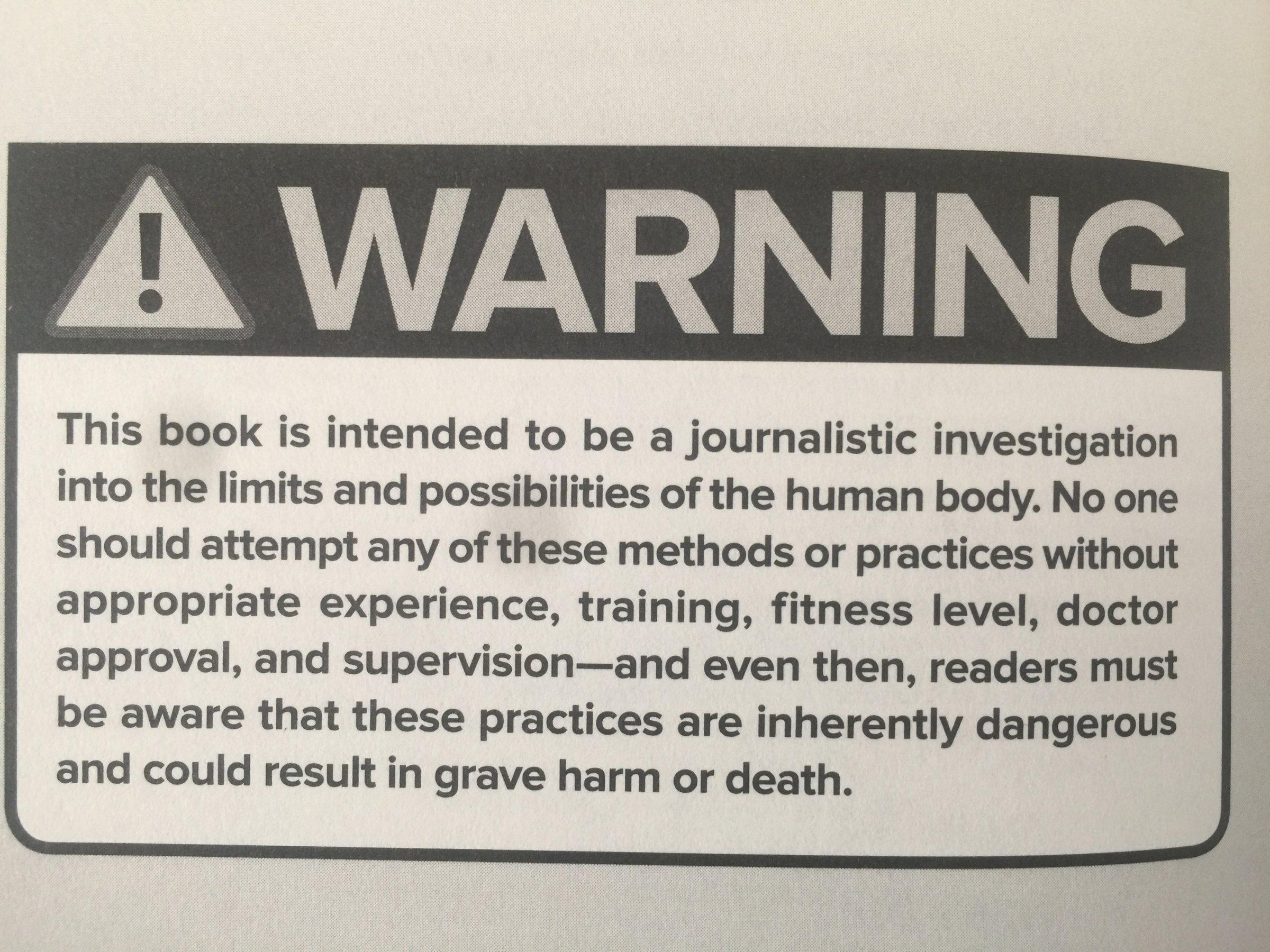

It's also worth noting that some of the things Hof has done — swimming in icy water, for example — have almost killed him and have killed other people who tried to replicate his feats. Carney's book begins with a warning that readers should not attempt these methods without the approval of a doctor and serious training and preparation. Even then, it says, "readers must be aware that these practices are inherently dangerous and could result in grave harm or death."

Danger aside, some athletes — like the legendary big-wave surfer Laird Hamilton, whom Carney trained with while embarking on his investigation — cite Hof's methods as influential. And there's promising data that suggests cold exposure could play a role in weight loss and help counteract the effects of type 2 diabetes.

The idea that it's possible to gain control over seemingly involuntary physical responses isn't limited to Hof's work. People like the open-water swimmer Lewis Pugh and certain monks have also been found to exercise some control over their internal body temperature — a seemingly superhuman ability.

Whether those skills can be taught and learned is the question. Hof thinks so, and though Carney leaves room for skepticism, he seems convinced, too.

"If you've been wrapped up in a thermogenic cocoon for your whole life, then your nervous system is aching for input," he wrote. "All you need to do is get a little bit outside of your comfort zone and try something out of the ordinary. Try finding comfort in the cold."

Read more:

• This chart is easy to interpret: It says we're screwed

• How Uber became the world's most valuable startup

• These 4 things could trigger the next crisis in Europe

Read the original article on Business Insider UK. © 2016. Follow Business Insider UK on Twitter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments