Invicta

Violet finds her prince

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For a boy wrestling with the ingenuities of Latin and as much in love with motor cars as with Michelangelo, no marque in 1947, the year of its post-war revival, could have been more romantic than the Invicta - invincible, unconquerable, but alas, resolutely invisible.

For a boy wrestling with the ingenuities of Latin and as much in love with motor cars as with Michelangelo, no marque in 1947, the year of its post-war revival, could have been more romantic than the Invicta - invincible, unconquerable, but alas, resolutely invisible.

Not for half a century have I encountered a Black Prince of 1947 (though a man at Christie's thinks he has). The Black Prince, I thought at the time, should be invictus rather than invicta, but then I knew nothing of Miss Violet Cordery, the marque's most celebrated record-maker, who was quite certainly victrix invicta, the Amy Johnson of the muddy track and open road, a forgotten heroine.

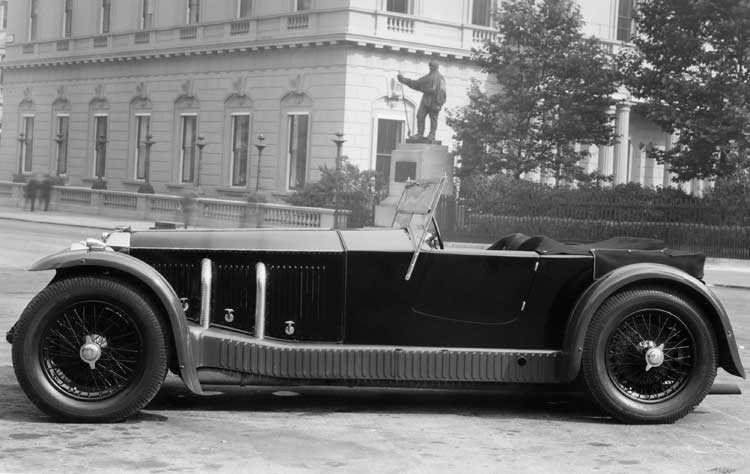

Backed by sugar money from Oliver Lyle, the first Invicta came onto the market in 1925, the engine supplied by Meadows (as with Lagonda and Jensen), the chassis designed by Sir Noel Macklin (who had already built two aborted marques), the bodies startlingly low and spare, the straight-line acceleration formidable, but the cornering (without independent front suspension) suspect, if not treacherous.

Enter Violet Cordery, Macklin's young sister-in-law, a venturesome flapper if ever there was one. In 1926, she drove the beast fast at Brooklands, her average speed was 73mph. In 1927, she set off round the world with it, clinging to the wheel for 10,000 miles in America, Australia and Africa. In 1929, the engine enlarged to 4.5-litres from the 3-litres of her 1926 machine, she kept an Invicta going for 30,000 miles in 30,000 minutes. There was then the lunacy of driving from London to Edinburgh and back in bottom gear - this in a car renowned for its flexibility in the very long-legged top that gave mile-a-minute cruising at only 2,000rpm and yet allowed its owners to start in top and trickle through traffic, never changing down. The adventures of the Toad-like Wodehouse woman did far less, however, to establish the marque than belting round Le Mans had done for Bentley, and production of the £1,000 chassis (coachwork extra) faltered in the 1931 Depression.

The S-Type revived Invicta's reputation and our affection and admiration for the marque is founded on this car - we think 77 were made in four years and 68 survive. It was exceptionally long and low, no matter which of the coachbuilders put a body on the chassis, essentially functional. It looked like no other car of its period; Donald Healey, later to make the cars that bear his name, won the Monte Carlo Rally with it in its first year.

The engine was the established Henry Meadows straight six of 4.5-litres (also used by Lagonda) then giving 115bhp; with a tweak or two this was raised to 140bhp in later models, giving it great success in Austrian Alpine Trials, Touring Trophy races and the peculiarly masochistic English sport of hill-climbing, but, even though Bentley was out of business until Rolls, its unscrupulous buyers in 1931, put the Rolls-Bentley into production in 1934, it made no headway in the market and did not fill that gap.

The marque's last attempt to stay in business was with a 1.5-litre version, but a scaled-down S-Type chassis was too much for the dinky engine and the price far too much to tempt young men away from the offerings of MG. Perhaps 60 were made before Invicta had to shut up shop.

Immediately after the Second World War, a new Invicta firm was formed and William Watson, who had been one of the engineers in its first incarnation, was invited to return - Macklin had just died. The venture was brave but doomed - just as Edward and Black Prince, the medieval hero after whom the new model was named, never assumed the throne of England, so this interesting car was too complex and flawed a character to unseat established rivals. It again used a Meadows engine of 3-litres, with three carburettors (a sure sign of sporting pretensions with a six-cylinder engine), mounted in "the strongest, lightest chassis frame of its type in existence", with independent suspension on all four wheels.

It was not a sports car, but a large saloon with a tall classical radiator surmounted by a sculpture of the Black Prince, sword in hand. It is all but impossible for a car to be sedate and rakish, but the unknown designer achieved this; he raked the radiator in a backward slope, divided the windscreen (curved glass was then virtually impossible to make for cars), spatted rear wings, and streamlined the roof and luggage boot with almost as much central European daring as Hans Ledwinka's great Tatra of 1936. The car's outstanding feature was the transmission. It was the first British car to dispense with a gearbox and offer only automatic transmission.

The system used, as the Invicta catalogue states, was "a hydrokinetic turbo-torque converter ... it contains no gearing, not a single moving part, but merely transmits engine power by means of a centrifugal pump to a turbine". In theory, this stepless transmission was always in the right ratio for the effort needed to accelerate, rush uphill or crawl in traffic, but this was still an age when a man was not a man if he did not enjoy double-declutching his crash box (tiresome with every gear change). The Black Prince emasculated a man and had no hope with the market at which it was aimed - it was certainly not the car for Violet Cordery.

In my childish hand I have scribbled "120bhp at 4,000rpm" in my old catalogue, but can now find no confirming evidence - but with two overhead camshafts and three carburettors, the old Meadows industrial engine may well have been capable of this.

The Black Prince was expensive. Announced with a list price of £2,300 and Purchase Tax of £639, it was only £300 cheaper than the standard Bentley saloon, and well over twice the price of the Jaguar. In June 1947, purchase tax on all cars costing £1,000 and more was doubled, raising the price of the Prince to a total of £3,579.

In 1948, a drop-head coupé of utterly conventional mid-Thirties design came out at a basic £2,500. By 1949, the Invicta in both forms cost more than £4,000, and the factory at Virginia Water closed forever.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments