‘Like death by a thousand cuts’: How microaggressions play a traumatic part in everyday racism

Little comments can have a big impact; Nicole Vassell looks at how microaggressions play a part in the jigsaw of daily racism and the damage they do over a lifetime

Every morning, Cam*, 30, crossed the same bridge to get to her London office. As usual, she was doing this journey a couple of hours earlier than she really needed to be - she always put in extra time compared to her white colleagues, so as not to appear lazy. However, every day she crossed that bridge she couldn’t help shake the feeling she wanted to jump off it, so desperate to avoid another day of racist microaggressions from fellow staff, an issue that had plagued the last four years of her career. “I honestly wished I was dead,” she tells The Independent. “I would have preferred taking my life to experiencing another day of what I was going through.”

Cam’s experiences ranged from managers telling her she looked unprofessional and should be “less of herself” when talking to clients, to being refused for promotions she was overqualified for. Her hair started shedding as a result and she developed anxiety-related irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). “I even got told I got up from my desk too often - so I started holding in my urine so they couldn’t say [that],” she says.

Cam spoke to senior management and HR about what was happening but says she was “not given support” from either department. In response her probation period got extended, before she says she was “eventually dismissed unfairly”. “When you raise the problem, it's reflected back to you and you're made to feel like it's your problem,” she explains.

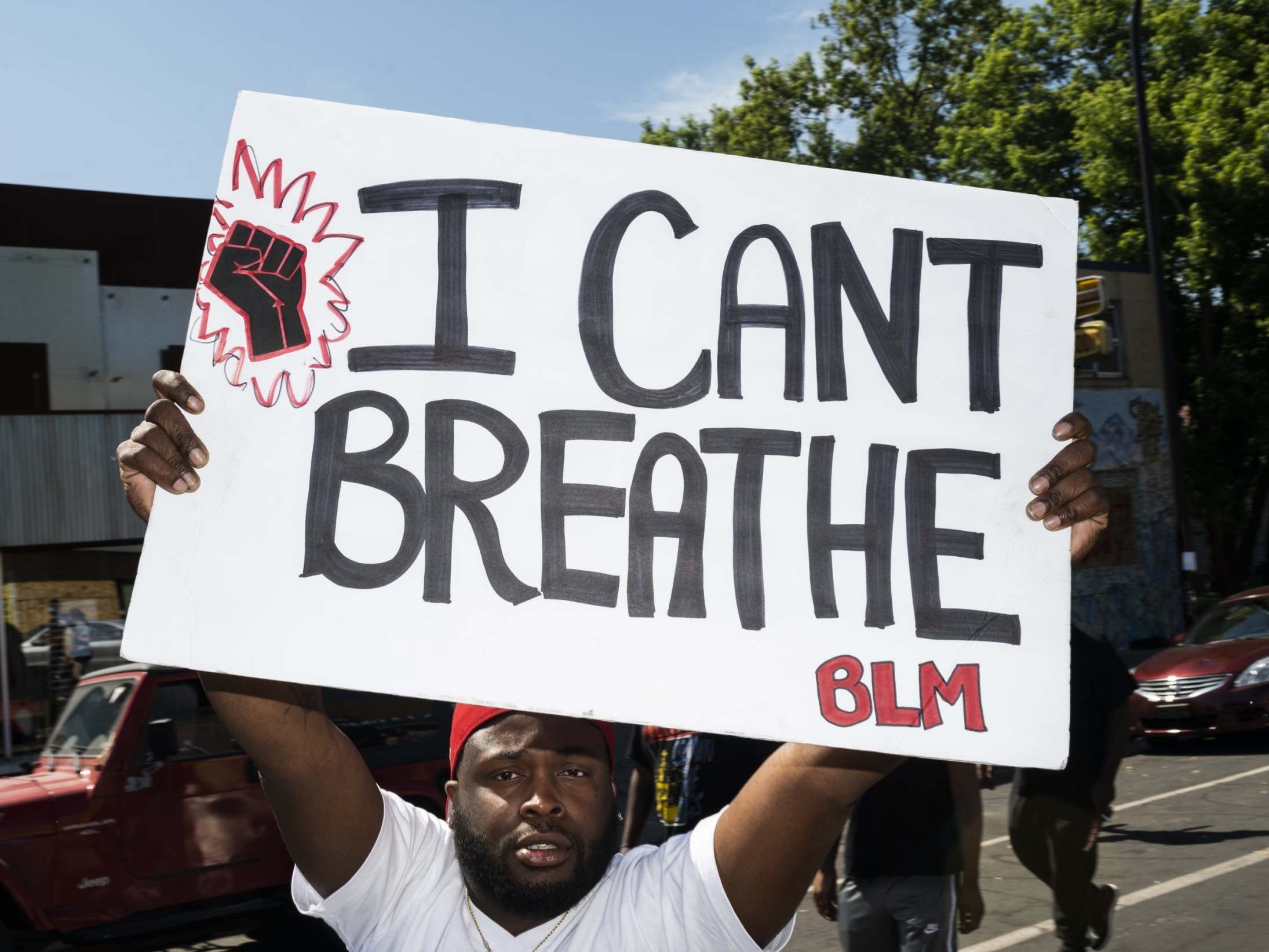

In the weeks following the killing of African-American man, George Floyd, by police in Minneapolis on 25 May, there has been much discussion about racism on both sides of the Atlantic. Although Floyd’s murder was an overt act of brutality, black people know this isn’t the only type of racial violence that occurs on a daily basis. As well as systemic issues like unequal pay (110,000 people have signed a petition to introduce mandatory ethnicity pay gap reporting in Britain) or black people being twice as likely to die in police custody, racism can be subtle and insidious.

Coined in the 1970s by psychiatrist and Harvard Professor, Chester M. Pierce, the term “microaggression” relates to these indirect expressions of discrimination and racism, which Pierce witnessed non-black people inflicting on African Americans (although the term can also be used in the context of sexism, homophobia and other discrimination as well).

Microaggressions may present as an innocuous comment or behaviour, but have the impact of highlighting a person’s “difference” from the majority represented group. Microaggressions can occur anywhere - from non-black people clutching their bags when black people pass by on the street, to a heterosexual person at a party assuming two LGBTQ+ people would get along, purely due to their mutual queerness.

Online search for the term microaggression has reached new levels in the UK following Floyd’s death and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement; in fact the data shows never as the world had so many people Googling microaggressions any time in our digital history.

At the start of June, HR expert Avery Francis saw the growing appetite for this knowledge and created a 10-slide presentation of microaggressions frequently experienced by black women. These include; "You are pretty for a black girl"; "You are so aggressive"; "You are so articulate"; and, the frequently-experienced question: "Can I touch your hair?" The post has now been liked over 360,000 times, gaining her 50,000 new followers, and receiving hundreds of comments, which cross the whole spectrum from support and reinforcement, to others claiming Francis is wrong, and that these comments are “intended as compliments”.

Francis says all of these comments qualify as microaggressions because they play into long standing historical stereotypes - that black people are lazy or uneducated (so being articulate is surprising) or that black people are more prone to being aggressive or violent. Others tap into issues around black women’s appearance: that attractiveness would always be surprising because western culture puts whiteness on such a pedestal, or a type of hair is so unfamiliar and other, that someone would want to touch it like an educational exhibit.

Microaggressions really chip away at your self worth, and it’s harder because the instances seem so small...

“It feels like death by a thousand cuts,” Francis explains. “[Microaggressions] really chip away at your self worth, and it’s harder because the instances seem so small.” It’s this element of perceived neutrality or individual smallness that can make microaggressions all the more sinister. After all the language and behaviour concerned can seem non-specific and more opaque than outright violence - because it isn’t always the words but the cultural and historical context concerning who is saying them, and to whom, that informs the impact they have.

But, just like more open expressions of racism, recipients of microaggressions can be left feeling angry, wronged, or belittled. According to psychologist Dr Samantha Rennalls, these “small comments” can generate an additional layer of damage to overt racial violence. “Because of their somewhat ambiguous nature, microaggressions come with an added layer of emotions,” she explains. “They can be confusing, sometimes leaving the recipient with a sense of uncertainty about why they are feeling hurt or offended.”

This difficulty in identifying the offence may discourage people from calling them out. Francis says: “In the workplace, if you have someone that makes a comment about your hair, you might not necessarily feel that it's totally appropriate to go to HR, because it's not overtly aggressive. It's something that isn't okay to you - but you’ll take it on the chin, so as to not make a fuss.” But, sadly, without the offender discovering what they’ve done, the cycle continues indefinitely.

Microaggressions are frequently attributed to occurring in the workplace, largely because it’s an institution in which we spend a lot of our waking hours. A poll by NASUWT, one of the UK’s largest teachers’ unions, found earlier this year that the majority of black and minority ethnic teachers in British schools have experienced “microinsults, microinvalidations and other forms of covert racism in the last year”. But it also occurs in other industries too.

On 14 June singer Misha B (Bryan), who appeared on The X Factor in 2011, took to social media to share a video about microaggressions she says she faced from contestants, production staff and judges. The singer told fans how inaccurate descriptions of her being “feisty”, “overconfident” and a “bully” chipped away at her confidence and made what should have been a joyous experience, an extremely painful one. “[They] created this whole narrative of me being overconfident because I’m black,” Bryan told her fans. “In [their] eyes, black girls should not be confident.” Bryan said her experience on the programme had left her feeling suicidal.

An X Factor spokesperson told The Independent: “We are very concerned to hear Misha’s comments regarding her experience on The X Factor in 2011. We are currently looking into this matter and are reaching out to Misha to discuss the important issues she has raised. The welfare of contestants is our priority and we are committed to diversity and equality.”

Bryan says she was diagnosed with PTSD after the experience, and claims that her absence from the music industry is due to her having to take time out to heal. She is not alone in the devastating long-term impact of microaggressions: multiple studies support the view that microaggressions have palpable repercussions past the moment of impact. Dr Samantha Rennalls says: “Long-term exposure to microaggressions has been associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety, possibly due to the impact that they have on self-esteem and/or the way in which one may feel powerless to challenge them.

Long-term exposure to microaggressions has been associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety, possibly due to the impact that they have on self-esteem and/or the way in which one may feel powerless to challenge them...

“When trauma is experienced, the body responds with an emotional and physiological stress response, which, when experiencing chronically, leads to a wearing down of psychological and physical wellbeing. This can be conceptualised as a “biological weathering" and is known to be associated with physical health problems such as hypertension and an impaired immune response,” she continues.

After leaving her job, Cam decided to try and transform a negative experience into a positive one: she set up an Instagram community to talk anonymously about what had happened, and encourage other black women to share their own stories. Ultimately she says she only made it through that time, without having a nervous breakdown, due to the support of her mother.

As society begins to reconcile the idea of transformation from the ground up, it is easy to focus on the most obvious signs of racism. But if we are to really address the deep-rooted nature we cannot overlook the micro-events that play out against the background of extreme racial violence. The daily aggressions that mount up and change the lives of black people forever.

*Names have been changed

If you have been impacted by mental-health related issues raised in this article you can call Samaritans on 116 123 for a free conversation and support.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks