How the chance you breaking up with your partner changes as your relationship goes on

Time really does help reduce the likelihood that two people go their separate ways

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Relationships that don't work out are bizarre things, miniature lives that burn out like stars. We all have our regrets—the one(s) that got away, the one(s) that never should have been.

But how often do things fizzle out? How frequently do two people go their separate ways? And how do the chances of breaking up change over time?

These are some of the many questions Michael Rosenfeld, a sociologist at Stanford, has been asking as part of a longitudinal study he started in 2009.

“We know a lot more about the relationships that worked out than the ones that didn’t,” said Rosenfeld. “The way the census and other surveys tend to collect data just doesn’t produce a very good picture. People also don’t recall failed relationships too well."

Rosenfeld, who has been tracking more than 3,000 people, is helping to fix that. And the answers he has found—at least those he has mustered so far (the study is ongoing)—are pretty revealing.

(He has also, by the way, uncovered some really interesting data about how people meet their partners)

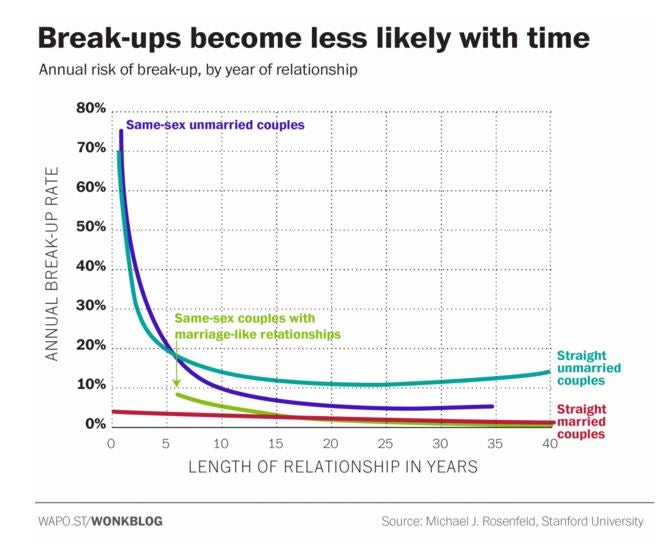

The chart below shows how the likelihood of breaking up changes as time goes by for straight and gay couples, both married and not.

There are obvious patterns, of course. Marriage, for instance, is a strong binder. Both straight and gay married couples are far less likely to separate than their non-married counterparts.

For same-sex married couples, the break-up rate falls from roughly 8 percent for those who have been together for 5 years to under 1 percent for those who have been together for at least 20 years. For heterosexual married couples, the rate falls from a shade over 3 percent to less than 1 percent over the same period. (If you're wondering why the break-up rate is so low, given divorce rates, understand that these are cumulative—the percentages compound over the years, creating an overall probability that is higher).

Unmarried couples on the other hand, both straight and gay, have much higher break-up rates—even when they have been together for more than twenty years.

There is little to be surprised about it here. Marriages, after all, are a necessarily more binding agreement. There are far more hurdles associated with annulling a marriage.

Where things get interesting is when one zeroes in on Rosenfeld’s data for non-married couples, which offer a rare window into the trajectory of modern relationships.

Broadly, the takeaway is that time really does help reduce the likelihood that two people go their separate ways. And rather quickly at that. Notice how steep the curve is for both straight and gay couples early on.

Sixty percent of the unmarried couples who had been together for less than 2 months during the first wave of Rosenfeld's study were no longer together when he checked up again the following year. But once a relationship lasts a year, the likelihood that it ends begins to drop precipitously. Over the first five years, the rate falls by roughly 10 percentage points each year, reaching about 20 percent for both straight and gay couples. And the rate continues to fall until about 15 years in, when it levels off for both—at just over 10 percent for gay couples and roughly 5 percent for straight couples.

Why? Well, it's fairly straightforward. As Rosenfeld noted in 2014, "the longer a couple stays together, the more hurdles they cross together, the more time and effort they have jointly invested into the relationship, and the more bound together they are."

As Rosenfeld continues his study, more of the gaps in his data will likely fill in. There is, at the moment, insufficient data for same-sex couples who have been married for fewer than 5 years (which is why that line begins later than the others). There is also too small a sample size for same-sex married couples who have been together for longer than 35 years. That he hopes to remedy, too. And it might very well mimic that which he has observed their straight counterparts, which rises after three decades (resultant, one might imagine, from some sort of mid or late-life crisis).

Still, it's been a fascinating dive, digging into the intricacies of human relationships. "One of the things I’ve learned from interviewing people face to face about their romantic histories is how complicated the stories can be."

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments