How St Dwynwen wrongly became known as the Welsh Valentine

The Welsh legend of St Dwynwen is anything but romantic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.February 14 is the day marked for lovers in many countries around the world, but in Wales there is another date traditionally associated with romance: St Dwynwen’s Day, January 25.

Dwynwen – pronounced [dʊɨnwɛn] – was the daughter of an early medieval king who became the Welsh patron saint of lovers. As you might expect, she has her own love story – although it’s not quite what we today would consider a romantic one.

As the earliest version of her tale goes, Dwynwen was deeply in love with a young man called Maelon Dafodrill, but when she rebuffed his premarital sexual advances, he became enraged and left her. Saddened and fearful, Dwynwen prayed to God, and soon enough her former suitor’s ardour was decisively cooled – he was turned into a block of ice. And for rejecting Maelon’s untimely advances, God allowed Dwynwen three wishes.

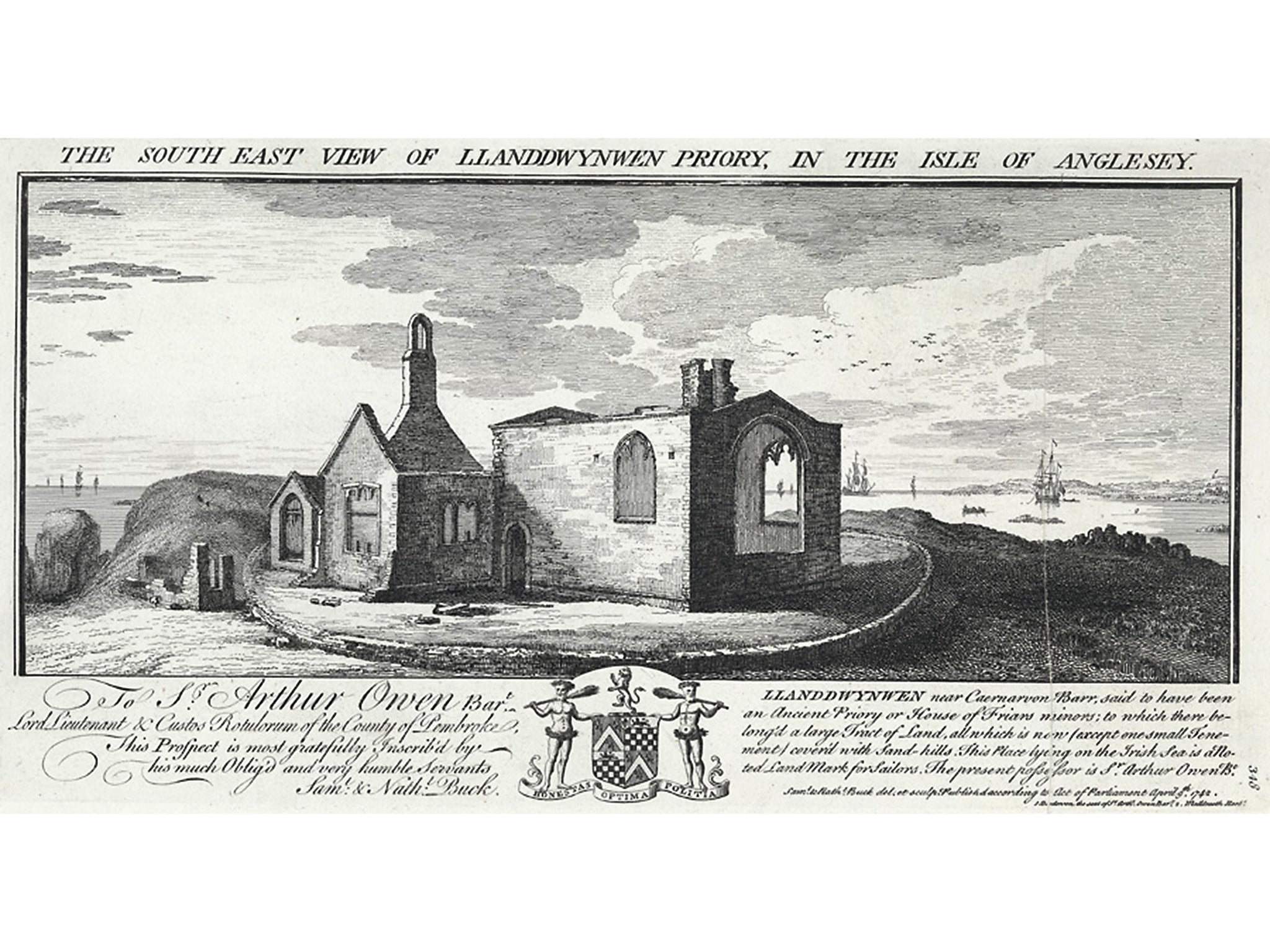

Her first wish was that Maelon should be defrosted at once. The second was that her prayers on behalf of “all true-hearted lovers” should be heard, so that “they should either obtain the objects of their affection, or be cured of their passion”. Her final wish was that she should never have to marry; she is said to have ended her life as a nun at the isolated church named after her, Llanddwyn, on the island of Anglesey.

Creating a legend

Although it echoes other medieval saints’ lives, Dwynwen’s story only appeared for the first time in the writings of the self-taught polymath Edward Williams (1747-1826), better known by his bardic name Iolo Morganwg. Now Morganwg, depending on your point of view, was either a creative literary genius or a shameless forger. Either way, it seems certain that Dwynwen’s story is not medieval at all, but rather a product of Morganwg’s vivid imagination.

However, Dwynwen may well have been a real woman: she is mentioned in early genealogies as one of the numerous saintly daughters of the semi-legendary fifth-century king, Brychan Brycheiniog. Part of a Latin mass from the early 16th century states that she walked on water from Ireland to escape the clutches of the Welsh king Maelgwn Gwynedd – although fleeing to Ireland might have been a better plan.

Our knowledge of the cult of Dwynwen is mainly based on two Welsh-language poems. The most famous was composed by medieval Wales’s greatest poet, Dafydd ap Gwilym, around the middle of the 14th century, and was certainly known to Morganwg. In it, the amorous poet calls for Dwynwen’s assistance as a “llatai”, or love-messenger, for him and his married lover Morfudd. Aware that his actions are, to say the least, morally dubious, Dafydd promises the saint that she won’t lose her place in heaven by helping the lovers. Indeed, ensuring that his back is at least metaphorically covered, he also calls on God himself to keep Morfudd’s interfering husband from interrupting the lovers in their woodland trysts.

The other poem, by the priest-poet Dafydd Trefor, dates from around 1500 and describes the pilgrims that thronged to her church to see her image and to seek restoration from her holy wells. Their offerings ensured that the church grew wealthy, although Dwynwen’s fame – inevitably – receded after the Reformation. But she never slipped into complete obscurity.

Modern reworkings

Dwynwen’s re-emergence began in earnest when extracts from Morganwg’s manuscripts were published with English translations in 1848. As a result, her story slowly but surely gained a foothold in the Welsh imagination. In 1886, for instance, composer Joseph Parry wrote the music for “Dwynwen”, a rousing chorus for male voice choirs. And in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Welsh newspapers in both languages would occasionally relate the story of the “Celtic Venus”.

In the 1960s, as the commercialisation of St Valentine’s Day continued apace, the first St Dwynwen’s Day cards were produced in Wales. Yet, unlike her ice-melting prototype, the modern Dwynwen proved to be a slow burner. Indeed, by 1993 a commentator stated that attempts to create a Dwynwen tradition were withering away.

But in the current century St Dwynwen’s Day is once more flourishing, bolstered by the media and the same kind of special offers that you see around St Valentine’s Day. And although St Dwynwen’s Day is more familiar to those who speak Welsh than to those who don’t, even this is slowly changing.

Does it say something about the passion of the Welsh that they have two days for lovers, Valentine – “Ffolant” as he is known in Welsh – and Dwynwen? Probably not. But the relationship between the two is revealingly ambivalent.

St Dwynwen’s day is in part a protest against the globalising commercialisation of St Valentine’s Day. But it’s also an attempt to find a place in the same marketplace for a distinctively Welsh product. It certainly shouldn’t be seen as a repackaging of St Valentine’s Day for a Welsh audience – that would be like marketing St David as the “St George of Wales”.

If you should ever find yourself in Wales on January 25, do make the most of the opportunity to follow your heart’s desires. The only advice I’d give you is this: don’t call Dwynwen the “Welsh Valentine”.

Dylan Foster Evans, reader in Welsh language and literature, Cardiff University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments