London is overpriced, flat and boring: so what is it for?

During cool Britannia, it was the place to be. But despite a revival of all things Nineties, people are abandoning a city that was once a magnet for dreamers and schemers. I know why, says Anna Hart, and what the capital needs to do to compete with its rivals...

Growing up in Belfast in the late 1990s and early 2000s, any kid with a creative mind, an adventurous spirit or an entrepreneurial streak had one ambition: get yourself to London. London was where our lives would begin, a vast international incubator for good ideas.

We’d be inspired by the talented generations before us, galvanised by influences from people from other countries, and surely we’d find people with the money to make things happen.

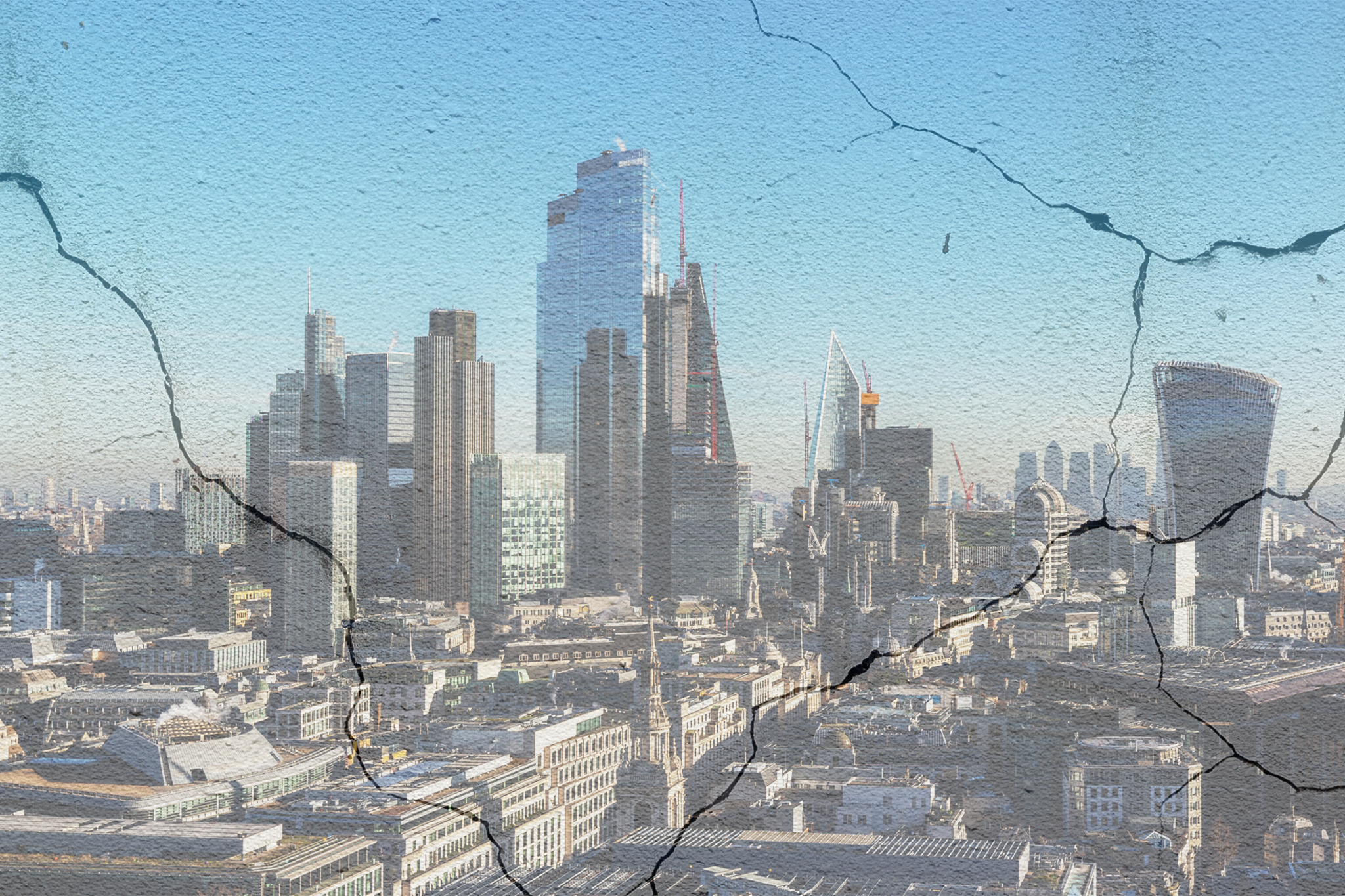

Today, London has plenty of people with money. But London is no longer happening. It feels flat, overpriced and boring. Why? Because London has pushed out the people with ideas, hopes and dreams that made it an exciting place to be.

Today, the most talented artists I know live in Liverpool, a brilliant city that only comes second to London in number of galleries and museums, but more importantly for creative people it’s where they can rent their home, studio or fledgling commercial space at prices 64 per cent lower than London.

At the end of last year, Time Out magazine named Liverpool’s Baltic Triangle as the UK’s coolest neighbourhood, and this should come as no surprise, because cool people can afford to be there.

Soho House, once London’s bastion of cash-fuelled creativity, opens its Manchester house in the old Granada Studios this year – which will delight my countless scriptwriter and broadcaster friends who’ve abandoned London and headed north in recent years, lured by a 30 per cent cut in their living costs just two hours from the capital.

The culinary entrepreneurs I know are choosing Glasgow, my old university city, where you can still rent a one-bedroom flat in a gorgeous old tenement building in the Southside for £795 a month.

The formerly cheapo studenty neighbourhoods of Shawlands and Finnieston are now cool gastro destinations, yet the cost of living (including rent) is half the price of London. It feels like London has forgotten that people who can’t live comfortably cannot create businesses, cannot make art or music, cannot work to help their community. And where the creatives and artists go, business and money follows – so this really matters.

For Dr Jordana Ramalho, associate professor of development planning for diversity at UCL’s The Bartlett Development Planning Unit, London’s changing character is most manifest in its dying nightlife: what was once a 24-hour city is now grey and square.

“I moved here in 2008, and much of what I felt made the city special related to the arts and creative spaces, but over the past five to ten years, we’ve seen venues shutting down, and community groups struggling.” The number of nightclubs in the city has fallen by more than half in the past 10 years, and LGBT+ venues have been particularly affected.

Most sociologists and urban planners blame successive Conservative governments, who have systematically defunded the arts, local councils and community groups, and pandered to international wealthy elites able to invest in London’s swathes of newly erected property… with Brexit bringing an additional and ongoing trade and talent crisis, and the pandemic compounding disillusionment towards the capital.

Professor Rowland Atkinson is an urban sociologist at the University of Sheffield, and his book, Alpha City: How London Was Captured by the Super-Rich, charts how London has moved “from cool, to Cool Britannia, to an Olympic peak achievement, to the hip, and then to a city associated more than anything else with the rich”.

“The global financial crisis of 2007-8 ushered in a new level of indulgence towards the wealthy, with tax cuts, quantitative easing, asset price inflation and a reduction of interest rates, all motivating the wealthy to pour money into cities that appeared safe bets in an unstable world,” explains Prof Atkinson. “We lost sight of what cities are for – as places where people live and thrive, where the city’s economy is set up to serve its residents’ needs, rather than being a magical playground for the super-rich.”

For many years, when people moaned about the high cost of living in London, my response was: “Get over it, because you’re in one of the greatest cities in the world.”

High living costs felt like a reasonable price to pay for success… and for front-row access to the amazing scene happening on your doorstep. But in 2018, I realised that struggling to survive financially in the city was nullifying my creativity, not nurturing it. I had been priced out of Brixton, then Stoke Newington, then Haringey, then Walthamstow. I lived in the city for 13 years and moved virtually every year, mainly because my rent went up.

With apologies to my many friends (high-flying chefs, music producers, doctors and academics) who now live in Leytonstone, I drew the line at Leytonstone and moved to Margate, where I was finally able to buy a flat for £129,000, get a mortgage, and breathe easy.

Moving to London to work at a men’s magazine in the mid-2000s was one of the best career moves of my life; so was leaving London in 2018. In Margate, people can afford their dreams, is how I explained it, to my confused editors and fellow journalists. Six years ago, my decision to leave London took some explaining. Today, everyone gets it.

London can easily afford to lose a few of us artists, sure, but London cannot afford to lose its magnetism, and that is what is happening right before our eyes

As an international travel and culture reporter, I judge a city by how well it treats its young people (they’re building the world we all have to live in), and its minority groups and more vulnerable people. I find these are better indicators of a city’s atmosphere and trajectory than its wealth… and this led me to the work of Professor Colin McFarlane, a lecturer in urban geography at Durham University.

“We’re all familiar with ‘most livable cities’ rankings, which tend to assess metrics like safety, job opportunities, housing and transport, but there’s an artificiality to this because, in fact, everyone experiences a different city, depending on our gender, ethnicity, age, wealth,” he says. “Measured economically, London has done very well in the past three decades, notwithstanding its inequalities. But I’m more interested in how London looks after its crowds.”

Prof McFarlane’s new book, Waste and the City: The Crisis of Sanitation and the Right to Citylife, looks specifically at sanitation as a marker of complacency in cities like London. “There are some boroughs in London – like Tower Hamlets with almost no provision for public toilets. This has a huge impact on the day-to-day experience of Londoners.”

Prof McFarlane points out that this lack of basic material provisions has serious consequences such as discouraging older people and those with certain illnesses from getting outdoors, as well as putting vulnerable people at risk of crime and putting delivery drivers off working in their field. London cannot afford such complacency, because cities are competing internationally for trade, talent, workers and investment and, right now, London is losing out to Glasgow, Birmingham, Manchester and Bristol… even Lisbon, Paris and Madrid.

Much has already been muttered about “creatives” leaving London, which is true, but the word “creative” is tarnished by smugness, and not really adequate to the task. It suggests that all London is losing is a few mopey musicians and self-indulgent performance artists, perhaps a vegan taco food truck or two, and opportunistic writers like me.

London can easily afford to lose a few of us, sure, but London cannot afford to lose its magnetism, and that is what is happening before our eyes. I would say it isn’t a coincidence that the London Stock Exchange (LSE) was recently reporting a 60 per cent decrease in listed companies since the 1990s – a time when Cool Britannia was in full swing in the capital. Where creatives thrive, the money follows. We are all connected.

London is also pushing out the people with big hearts: medical professionals can no longer afford to live near the hospitals they work in, teachers and community leaders are being priced out of the very communities they’re working tirelessly to improve, as well as international workers who travel to London to work hard in the service industries for a better life for them and their families. People with big ideas, big purposes and big dreams are the people who make London tick. And when the heart stops ticking, we all know what happens next.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments