China’s Singles Day retail phenomenon will blow Black Friday out the water

Will the rest of the world catch up with a trend which encourages gift buying for yourself?

For the past few years, Black Friday has become a focal point for many US and UK retailers – and for media outlets hungry for images of shoppers bursting into stores in pursuit of posh televisions.

The event, supposedly named after the moment when retailers move into profit for the year, has quickly escalated into a four-day shopping festival. But it is not the only game in town – or even the biggest.

Black Friday falls the day after Thanksgiving in the US (November 23 this year) and is followed up by a long-weekend extravaganza which culminates in the online-focused “Cyber Monday”. It has recalibrated, and brought forward, many consumers’ pre-Christmas shopping plans.

However, unlike Black Friday, China’s 11 November “Singles Day” is still predominately focused on local consumers and completely dominated by one online retailer – Alibaba.

The economic impact of Black Friday is dwarfed by this online one-day retail festival from China. Singles Day has gone under the radar for most of the general public in the West, but in 2016, Chinese shoppers spent an incredible $17.8bn (£13.5bn) in 24 hours on the Alibaba online platform – China’s Amazon equivalent.

This online sales bonanza shifts more goods than the Black Friday and Cyber Monday sales days in the US combined. Black Friday in the US saw online sales hit a record of just over $3bn (£2.2bn) in 2016.

Origins

Singles Day started as an obscure “anti-Valentine’s” celebration for single people in China back in the 1990s. The popular story is that it was started by students at Nanjing University who celebrated their singledom by treating themselves. It takes place on 11 November every year and is sometimes known as “bare sticks holiday”, after the way the date is written (11/11).

The event is also known as “Bachelors’ Day”, and it’s not hard to see why. China has a surplus of males caused by years of the government’s “one child” policy. By 2020, sociologists expect the gender imbalance to have widened to 35 million and by 2030, it is estimated that one in four Chinese men in their late 30s will never have married. That is a big market.

Black Friday was, of course, initially driven and then “exported” to the UK and other markets by major US retailers, specifically Walmart and Amazon. In China, it was the e-commerce giant Alibaba which adopted Singles Day in 2009, just as online shopping started to explode.

It has now become a day when everyone, regardless of their relationship status, buys themselves gifts. Alibaba spotted this as a chance for retailers to generate interest and excitement and to boost sales in the lull between China’s Golden Week national holiday in October and the peak Christmas season.

Like much of the global growth in online sales, Singles Day has been driven by mobile. Nowhere is this more stark than in China where, with 1.3 billion smartphone users, mobile shopping is huge. Around 37 per cent of Chinese shoppers buy products using their phones, compared to the global average of 13 per cent.

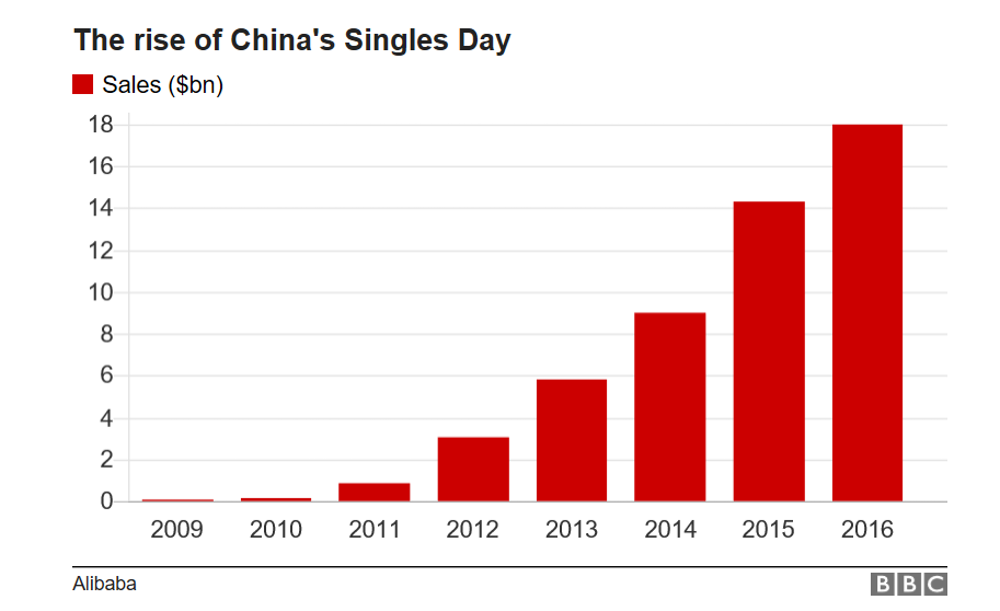

We’ve seen that Alibaba’s sales numbers for Singles Day are astonishing. And the growth has been too. The chart below shows how Singles Day sales for Alibaba have risen over the past seven years. Last year alone, sales were up 32 per cent on the previous year.

According to Alibaba, during the event on 2016 they processed more than a billion payment transactions in total, with 120,000 transactions per second at peak and their distribution system processed more than 657 million delivery orders.

Analysts have predicted this year’s event could see Alibaba rack up sales of $20bn (£1 5.2bn) despite a slowdown in China’s economy, partly due to it having a broader audience.

Copy cats

Of course those kinds of numbers attract the interest of Western retailers too and the 2016 event saw 37 per cent of total buyers purchasing products from international brands or merchants. Companies like US retailers Costco and Macys as well as Britain’s Top Shop and House of Fraser have marketplaces on Alibaba’s Tmall site have already got involved.

And, for the first time, Alibaba’s 2017 Singles Day festival will bring more than 100 Chinese brands to overseas buyers, offering special promotions targeting over 100 million overseas Chinese consumers in Asia and around the world.

There is one rather sensitive obstacle to the adoption of Singles Day in the UK, however. The eleventh day of the eleventh month is Armistice Day when Britain marks the end of the First World War and the nation remembers all those who have died in military service. There will be many who think it distasteful to run a shopping event on that day. However, as David McCorquodale, head of retail at KPMG, pointed out: “Singles Day in China is the biggest promotions day in the world. [The date] will stall its entry to the UK, but not forever.”

Given the rapid globalisation of most retail trends and the way online retail now allows immediate access to millions of products from thousands of manufacturers, it is indeed impossible to envisage that Singles Day won’t extend it’s reach, in some form, to Western consumers very quickly.

Nelson Blackley is a senior research associate at Nottingham Business School, Nottingham Trent University. This article was originally published on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks