Unheard recording of secret call between Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher shows how the President sweet-talked his way out of Grenada invasion crisis

The US had invaded Grenada, a former British colony, against her wishes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A recording of a previously top-secret phone call between Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher has revealed how the former US President sweet-talked his way out of recriminations over the 1983 invasion of Grenada.

Thatcher was said to be outraged, along with the rest of the world, at America’s shock incursion into the former British colony, which came without warning or discussion with the UK Government.

Westminster was further embarrassed by the fact that just a day before, the Foreign Secretary had assured Parliament that he had no knowledge of any American intervention.

The Prime Minister made her views known in the build-up to Operation Urgent Fury, on 25 October, saying she was "deeply disturbed" by the prospect of military action but Reagan claimed he was not told until it was too late to pull back the troops.

The US invaded the Caribbean island to crush a revolutionary socialist government after its leader was murdered and prevent the alleged Cuban and Soviet militarisation of Grenada.

In an audio recording of a call the next day, released by the New York Post, a slightly nervous Reagan is heard apologising to a distinctly frosty Thatcher for invading a former British colony against her wishes.

The Prime Minister later recalled that she was “not in the sunniest of moods” when she took the call in her room at the House of Commons during an emergency debate on the crisis.

Regan opened the conversation saying “if I were there Margaret, I'd throw my hat in the door before I came in,” referring to the Wild West tradition for visitors unsure of the welcome they would receive.

“There’s no need to do that,” came the clipped reply.

Reagan quickly apologised, saying the US regretted “very much the embarrassment caused” and claiming he was unable to reveal the invasion plans even to her because of concerns over a security leak.

“I'm sorry for any embarrassment that we caused you, but please understand that it was just our fear of our own weakness over here with regard to secrecy,” he added.

He had planned the military action “in his pyjamas” in a hotel suite while on a golfing holiday in Georgia.

When the President got word of Thatcher’s opposition, he said, “zero hour” had passed an American forces were on their way in.

“I want you to know it was no feeling on our part of lack of confidence at your end. It’s at our end,” the President added, assuring the Prime Minister that the British governor of the island and his family were safe.

Thatcher countered that she knew all “about sensitivity” after the Falklands and had exercised every caution in secure telephone calls, suggesting she should have trusted with the information.

“Well let’s hope it’s soon over Ron, and that you manage to get a democracy restored,” she said.

When Regan recounted a conversation using the phrase “kith and kin”, suggesting it could be an American term, she could not resist one-upping him by replying: “It’s one of ours.”

“There is a lot of work to do yet, Ron,” she cautioned. “And it will be very tricky.”

A BBC report from the day said 1,900 US marines and army rangers, helicopter gunships and 300 soldiers from six other Caribbean nations were involved in the invasion.

It was called a “flagrant violation of international law” by a subsequent United Nations resolution, which was vetoed by the US.

Hundreds more troops were sent in amid heavy fighting over the next few days and as the invasion force grew to more than 7,000 the defenders either surrendered or fled into the mountains.

The US Government put the total death toll at 45 Grenadians, 24 Cubans and 19 Americans, and the operation ended on 15 December.

Grenada had gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1974 and the Marxist-Leninist New Jewel Movement, popular with much of the population, seized power in a coup five years later and suspended the British-formulated constitution which was restored after the invasion.

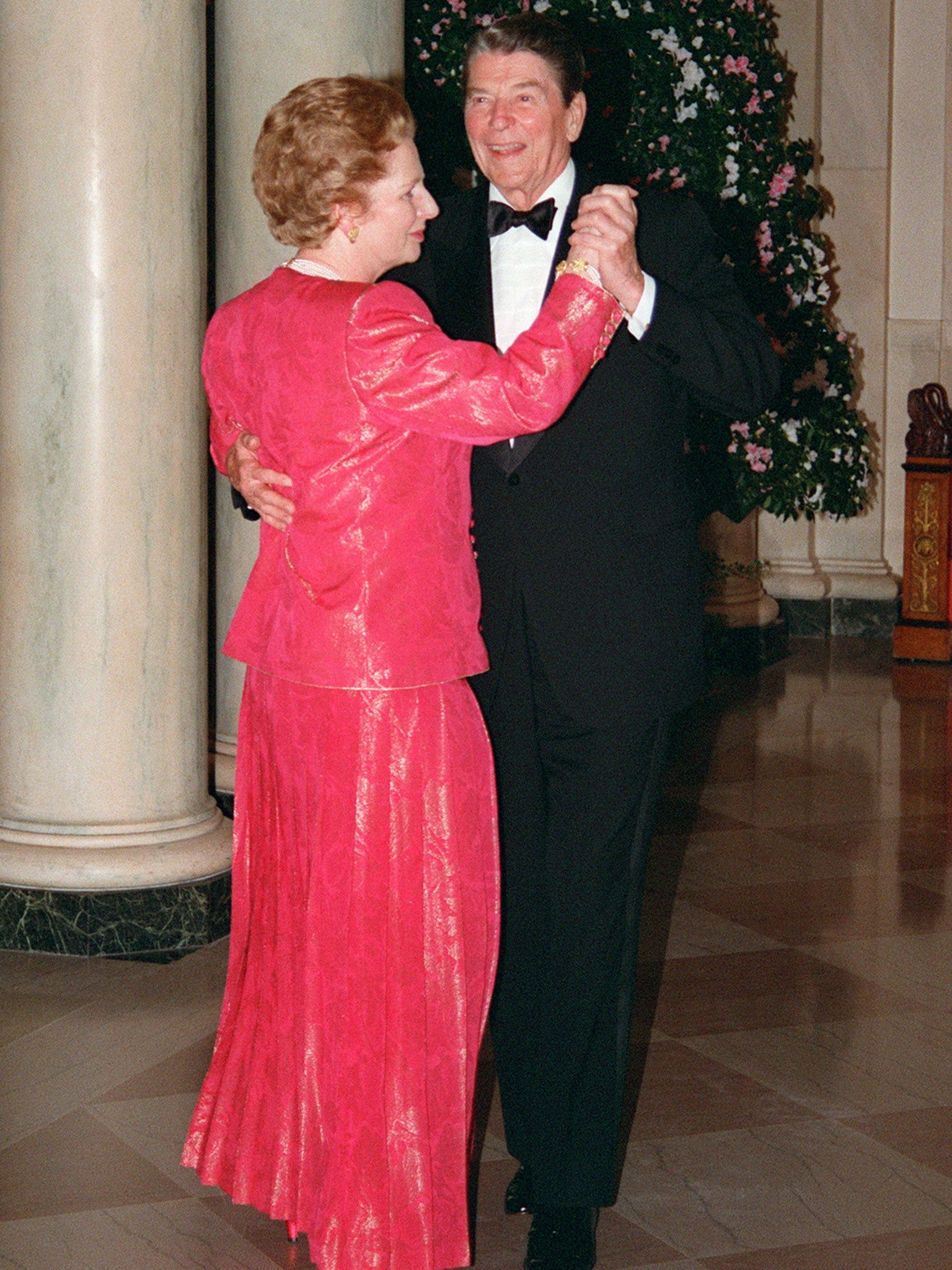

Although the saga caused a temporary slide in relations between Britain and America, particularly in the public eye, Regan and Thatcher’s alliance survived relatively unharmed.

They are often cited as one of the most prominent examples of the “special relationship” between leaders of the UK and US.

Their friendship is demonstrated in the phone call, which becomes warmer and more relaxed the longest it goes on, and ends on a distinctly cordial note.

Thatcher asked after Reagan’s wife, Nancy, after thanking him for ringing her, adding “give her my love”.

“I must return to this debate in the House. It is a bit tricky,” she adds.

Reagan replied: “All right. Go get ’em. Eat ’em alive.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments