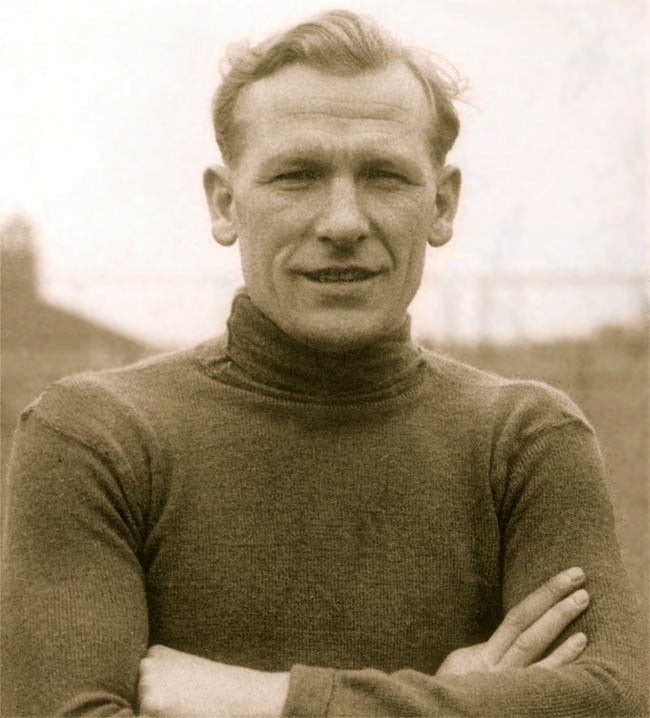

Bert Trautmann: Germany should never again go to war over race or ideology

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Germany should never again go to war over race or ideology, says the former Nazi paratrooper and legendary Manchester City goalkeeper, Bert Trautmann in an interview to mark the 70th anniversary of Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s attack on Russia.

“Growing up in Hitler's Germany, you had no mind of your own. You didn't think of the enemy as people at first” says the 87-year- old who won the Iron Cross for bravery on the Eastern Front and the OBE for fostering Anglo-German relations after the war. “Then, when you began taking prisoners, you heard them cry for their mother and father. You said 'Oh'. When you met the enemy, he became a real person”.

Operation Barbarossa commenced on 22 June 1941 and was the biggest land invasion in the history of human conflict. Three million Germans invaded Stalin’s Russia in a war which was to finally end nearly four years later in the total defeat of Nazi Germany. At the time Trautmann was only 17 years old and was with his unit Nachrichten Regiment 35 on the Polish Russian border.

“Then came the signal to attack and we were out of the protection of the farm buildings, stumbling across an open field in the first light of dawn. The Luftwaffe had gone before us, bombing airfields, villages, towns and munition factories. Next came the panzers, the pride of the German army, spearheading across terrain with a force and speed which surprised even the most battle hardened soldiers."

Unbeknown to Trautmann accompanying the invasion were members of the SS and Einsatzgrupen, or mobile killing units. As part of Hitler's plan for lebensraum or living space in the east they had orders directly from Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Reich Security Office, to execute all Jews.

No one knows how many Jews died in Russia as a result of their activities but the figure is likely to be in excess of two million. To piece together what is known the International Institute of Holocaust Research held a conference on Monday to mark the anniversary examining how the beginning of the mass murder of Jews coincided with the German advance eastwards.

Dr Yitzhak Arad, a former partisan, and chairman emeritus of the research institute said “With the beginning of the war against the Soviet Union the Wehrmacht participated in the murder of Jews. As the advance slowed so the murder of the Jews in a few places was delayed as they were needed for slave labour. Many Soviet Jews still had mistaken beliefs in the great military power of the Red Army and that antisemitism among Soviet citizens was a matter of the past.”

Trautmann was to see for himself the true horrors of that extermination one dark cold night in October 1941. He and his fellow paratrooper Peter Kularz had gone to investigate the sounds of shooting when they saw an area in the forest lit up like the football field at night with floodlights.

“It was hard to take in. There were trenches dug in the ground about three metres deep and fifty metres long, and people were being herded into them and ordered to lie face down, men, women and children. Einsatzgruppen officers stood above, legs astride, shouting; a firing squad was lined up at the edge of the trenches, shooting into them. For a while everything went quiet, then another group was ordered forward and the firing squad shot another salvo into the trench”.

Trautmann and Kularz got down on their bellies and crawled away, before running for their lives. If they had been seen both of them would have been shot on the spot as the Einsatzgruppen wanted no witnesses. Seventy years on Trautmann is still haunted by the incident and finds it difficult to discuss. "Of course it touched me seeing this. If I'd been a bit older I'd probably have committed suicide."

The killing fields of Russia were a long way from the playing fields of Germany where as a 10 year old mad on football Trautmann had joined Tura Bremen football club. “At that age you just want adventure. It was just like the boy scouts. It was fun - sport, sport, sport. The idea that we were Nazis at the time is nonsense. The indoctrination came later. At 10 you have no mind of your own."

After the Nazis came to power in 1933 his sporting ability was soon picked up upon by the regime and he went on to represent his athletic team at the youth Olympics in Berlin in 1938. He also joined the Hitler Youth and was indoctrinated that Jews were subhuman and responsible for all Germany’s ills.

It was only after the war as a British prisoner of war that he came to see them in a different light. Trautmann was told of the concentration camps and forced to watch a film about the Holocaust "My first thought was: 'How can my countrymen do things like that? But Hitler's was an utter totalitarian regime."

To ‘re-educate’ him the former Nazi paratrooper was then forced to report to Jewish officers at a POW camp and was quizzed on his views. At first he rebelled and ended up fighting with his interrogators. But driving another Jew, Sergeant Hermann Bloch, changed his mind. "I quickly came to see Bloch, and every other Jew, as human beings. At first I sometimes lost my temper with him, but, in time, I talked to him as if he was just another English soldier. I liked him."

In the camp Trautmann's sporting ability was again quickly noticed and he started regularly playing football with other inmates. When he was released he went on to play as a goalkeeper for the second division side St Helen’s Town before signing for the great Manchester City in 1949. Given the times perhaps unsurprisingly when his signing was announced in the press Manchester’s Jewish community reacted with fury. It culminated in 25,000 people standing outside the stadium shouting ‘Nazi’ and ‘War Criminal’ and threatening to boycott the club.

Then an open letter appeared in the Manchester Evening Chronicle from Dr Altmann, the communal rabbi of Manchester. “Despite the terrible cruelties we suffered at the hands of the Germans” he wrote, “we would not try to punish an individual German, who is unconnected with these crimes, out of hatred. If this footballer is a decent fellow, I would say there is no harm in it. Each case must be judged on its own merits”.

It was to be a turning point in Trautmann's life and career. From then on despite his paratrooper past he was to be judged not on his nationality but on his ability as a goalkeeper. Over the next 15 years he made 545 appearances for Manchester City before retiring in 1964.

Trautmann now dedicates his time to a foundation which bears his name and helps improve Anglo-German understanding through football. A very popular biography entitled Trautmann's Journey by Catrine Clay was published last year. However, for football fans Trautmann will always be remembered for one game - the 1956 FA Cup in which Manchester City took on Birmingham City.

With just 17 minutes of the game remaining Trautmann had collided with a Birmingham player seriously injuring himself. But despite intense pain he continued to play on and performed a couple of crucial saves which helped Manchester City to win 3–1. It was only when he collected his winner's medal that he noticed his neck was crooked. Three days later an x-ray revealed it had been broken.

“If the impact hadn't been so hard, if the third vertebrae hadn't pushed itself under the second, I would have been dead. Or paralysed. One of the two. So I was very, very lucky, wasn't I?"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments