What I wish I’d known about my knees

After years of tennis, jogging and skiing, Jane E Brody started to encounter chronic knee pain, but the treatments available were found to be wanting

Many of the procedures people undergo to counter chronic knee pain in the hopes of avoiding a knee replacement have limited or no evidence to support them. Some enrich the pockets of medical practitioners while rarely benefiting patients for more than a few months.

I wish I had known that before I had succumbed to wishful thinking and tried them all.

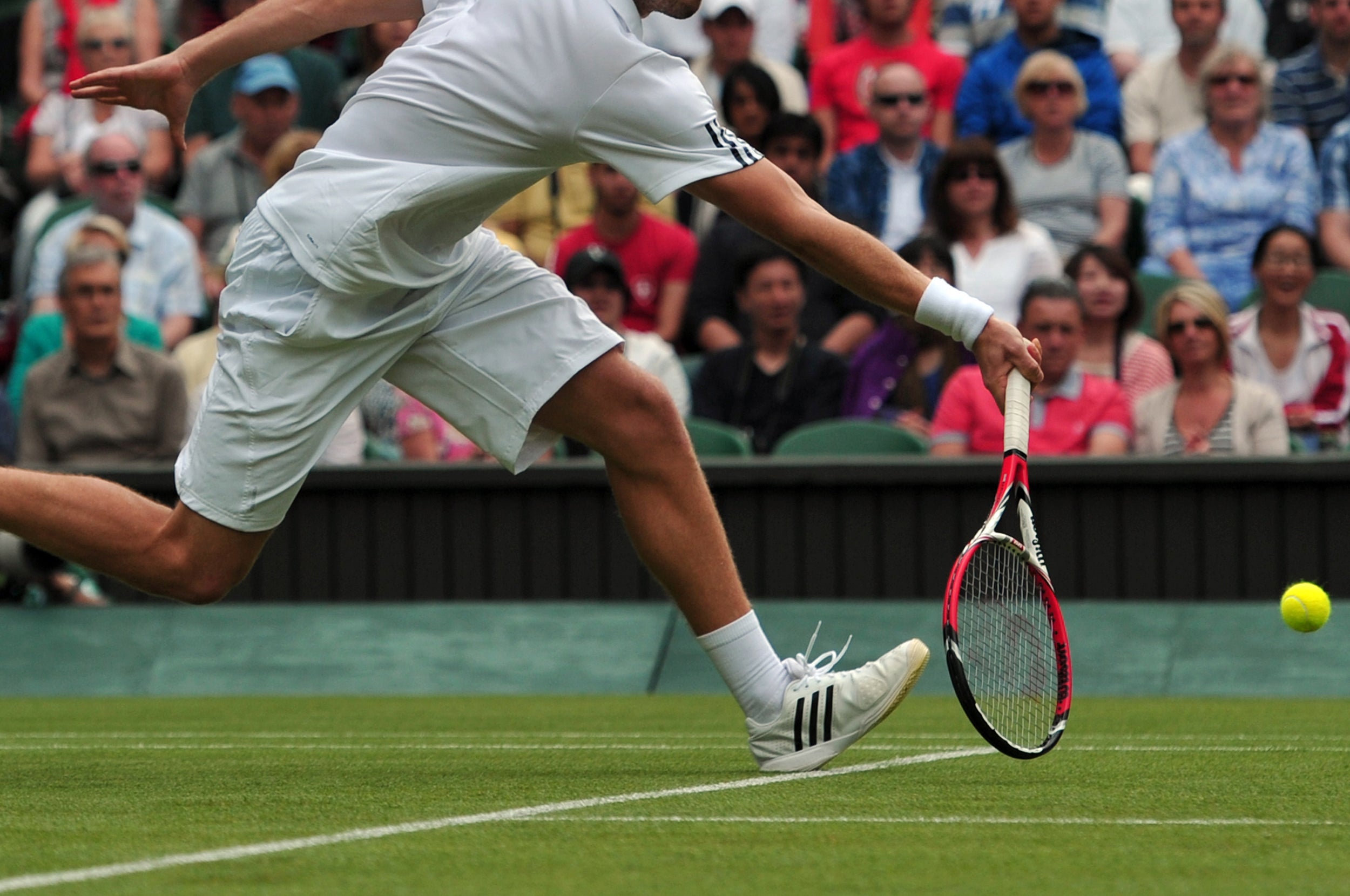

After 10 years of jogging, decades of singles tennis and three ski injuries, my 50-plus-year-old left knee emitted clear signals that it was in trouble. I could still swim and ride a bike, but when walking became painful, I consulted an orthopedist who recommended arthroscopic surgery.

The operation, done with tiny incisions through a scope, revealed a shredded meniscus, the cartilage-like disc that acts like a cushion between the bones of the knee joint. The surgeon cleaned up the mess, I did the requisite postoperative physical therapy, then returned to playing tennis, walking, cycling and swimming.

Fast-forward several years until increasing pain forced me off the court and X-rays revealed bone-on-bone arthritis in both knees. A sports medicine specialist suggested a series of injections of a gel-like substance, hyaluronic acid, meant to lubricate the joint and act as a shock absorber. The painful, costly injections were said to relieve knee pain in two-thirds of patients. Alas, I was in the third that didn’t benefit.

With walking now painful and my quality of life diminished, I finally had both knees replaced, which has enabled me to walk, cycle, swim and climb for the past 13 years.

Serious questions are now being raised about the benefits of the arthroscopic procedures that millions of people endure in hopes of delaying, if not avoiding, total knee replacements.

The latest challenge, published in May in BMJ by an expert panel that systematically reviewed 12 well-designed trials and 13 observational studies, concluded that arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscal tears resulted in no lasting pain relief or improved function.

Three months after the procedure, fewer than 15 per cent of patients experienced at best “a small or very small improvement in pain and function”, effects that disappeared completely within a year.

As with all invasive procedures, the surgery is not without risks, infection being the most common, though not the only, complication.

Furthermore, the panel added: “Most patients will experience an important improvement in pain and function without arthroscopy.”

That, in fact, was the experience of a friend who, at about age 70 and an avid tennis player, consulted the same surgeon who had operated on my knee years earlier. My friend was told he had a torn meniscus that could be repaired arthroscopically, but he chose not to have the procedure. Instead, after several weeks of physical therapy, the pain had subsided, he returned to the court and has been playing without a recurrence for at least eight years.

“Arthroscopic surgery has a role, but not for arthritis and meniscal tears,” Dr. Reed AC Siemieniuk, a methodologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, and chairman of the panel, said in an interview. “It became popular before there were studies to show that it works, and we now have high-quality evidence showing that it doesn’t work.”

Arthroscopic surgery can sometimes be useful, he said, citing as examples people with traumatic injuries and young athletes with sports injuries. My son Erik is a case in point. When he was 23, Erik was playing basketball when he sustained a rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament in one knee that was successfully repaired arthroscopically. He’s been playing tennis and basketball on that knee without pain for the past 24 years.

The panel noted that about one-quarter of people older than 50 experience knee pain from degenerative knee disease, a percentage that rises with age. Arthroscopic procedures for this condition “cost more than $3bn (£2.3bn) per year in the United States alone,” the report stated, suggesting that it was a near-complete waste of money.

Other common interventions include steroid injections into the knee. These can reduce painful inflammation, but if used repeatedly, steroids can speed the development of arthritis in the joint. A study published in May in JAMA (the Journal of the American Medical Association) by researchers at Tufts Medical Centre found that the injection of a corticosteroid every three months over two years resulted in greater loss of knee cartilage and no significant difference in knee pain compared to patients who received a placebo injection.

The value of the other procedure I had, injections of hyaluronic acid (Synvisc and Monovisc are common brands), has somewhat better research support for patients with knee pain. One large study, published last year in Plos One, included more than 50,000 patients treated with one or more courses of these injections and compared them to more than 131,000 patients who had no injections.

For those who underwent five or more courses, the injections delayed the average time to a total knee replacement by 3.6 years, whereas those who had only one course averaged 1.4 years until knee replacement, and those who had no injections had their knees replaced after an average of 114 days.

Siemieniuk conceded that treatment for degenerative knee arthritis can be “frustrating for both doctors and patients” because there is no clear answer as to what will help which patients.

Until there is better evidence, he suggested the following approaches that are known to help keep many patients out of the operating room.

- If you are overweight, lose weight. The more you weigh, the more pressure on your knees with every step and the more they are likely to hurt when walking or climbing stairs.

- Pay attention to the activities that aggravate knee pain and try to avoid those that are not essential, like squatting or sitting too long in one place.

- If the pain is bad enough, take an over-the-counter pain reliever like acetaminophen (Tylenol and others) or an NSAID (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug) like ibuprofen or naproxen.

- Probably most helpful of all, undergo one or more cycles of physical therapy administered by a licensed therapist, perhaps one who specializes in knee pain. Be sure to do the recommended exercises at home and continue to do them indefinitely lest their benefits dissipate.

- Consider consulting an occupational therapist who can teach you how to modify your activities to minimize knee discomfort.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks