The silence that still surrounds periods

Periods are a taboo subject the world over – but that's starting to change

Let’s begin with the obvious: Every woman in the history of humanity has, or has had, a period. Each month, her uterus sheds its lining, sending blood flowing out through her vagina. This process is as natural as eating, drinking and sleeping. There’s no human race without it. Yet most of us loathe talking about it.

When girls first start their periods, they embark on a decades-long journey of silence and dread. Periods hurt. They cause backaches and cramps, not to mention emotional turmoil – and this goes on every month, for 30 to 40 years.

In public, people discuss periods as often as they discuss diarrhea. Women shove sanitary pads or tampons up their sleeves on their way to the bathroom so no one knows it’s their time of the month. They get blood stains on their clothes. They stick wads of toilet paper in their underwear when they’re caught without supplies. Meanwhile, ad campaigns sanitise this bloody mess with scenes of light blue liquids gently cascading onto fluffy white pads while women frolic in form-fitting white jeans.

In a 1978 satire for Ms. magazine, feminist Gloria Steinem answered the question that so many women have asked: “What would happen, for instance, if suddenly, magically, men could menstruate and women could not? Her reply? "Menstruation would become an enviable, boastworthy, masculine event." She envisioned a world where “men-struation” justifies men’s place pretty much everywhere – in combat, political office, religious leadership positions and medical schools. We’d have “Paul Newman Tampons” and “Muhammad Ali’s Rope-a-Dope Pads”.

Nearly 40 years later, Steinem’s essay still stings because “menstrual equity” has gone almost nowhere. Women's sanitary products have always been considered a "luxury" – and therefore non-essential – item and so taxable. Here in Britain they are subject to VAT; after much pressure from equal rights groups, David Cameron said in a speech to the House of Commons: "Britain will be able to have a zero rate for sanitary products, meaning the end of the tampon tax," according to a 21 March news story that appeared in the Independent. He said the European Commission “will publish a proposal to allow countries to extend the number of zero rates for VAT”.

In most public and private places today, women are lucky if there’s a cranky machine on the wall charging a few quarters for a pad that’s so uncomfortable you might prefer to use a wad of rough toilet paper instead. You can pay for a parking spot with a credit card, but have you ever seen such technology on a tampon machine in a women’s bathroom? The situation for homeless women is even more dire. You need only read May Oppenheim’s article, “For Homeless Women, Having a Period Isn't a Hassle – It's a Nightmare”, published by Vice on 23 January 2015, to get a picture of just how dire.

If all this sounds unfair, try getting your period in the developing world. Taboos, poverty, inadequate sanitary facilities, meagre health education and an enduring culture of silence create an environment in which girls and women are denied what should be a basic right: clean, affordable menstrual materials and safe, private spaces to care for themselves.

At least 500 million girls and women globally lack adequate facilities for managing their periods, according to a 2015 report from UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO). In rural India, one in five girls drops out of school after they start menstruating, according to research by Nielsen and Plan India, and of the 355 million menstruating girls and women in the country, just 12 per cent use sanitary napkins.

“In today’s world, if there’s nobody dying it’s not on anyone’s agenda,” says Venkatraman Chandra-Mouli, a WHO scientist who’s worked in adolescent health for the past 20 years. “Menstrual problems don’t kill anyone, but for me they are still an extremely important issue because they affect how girls view themselves, and they affect confidence, and confidence is the key to everything.”

For something that has more than 5,000 slang terms (on the blob, on the rag, got the painter’s in, red wedding), the period is one of the most ignored human rights issues around the globe – affecting everything from education and economics to the environment and public health – but that’s finally starting to change. In the past year, there have been so many pop culture moments around menstruation that Cosmopolitan said it was “the year the period went public”.

We’ll never have gender equality if we don’t talk about periods, but 2016 signalled the beginning of something better than talk: it’s becoming the year of menstrual change. There’s a movement – propelled by activists, inventors, politicians, start-up founders and everyday people – to strip menstruation of its stigma and ensure that public policy keeps up. For the first time, people are talking about gender equality, feminism and social change through women’s periods, which, as Steinem puts it, is “evidence of women taking their place as half the human race”.

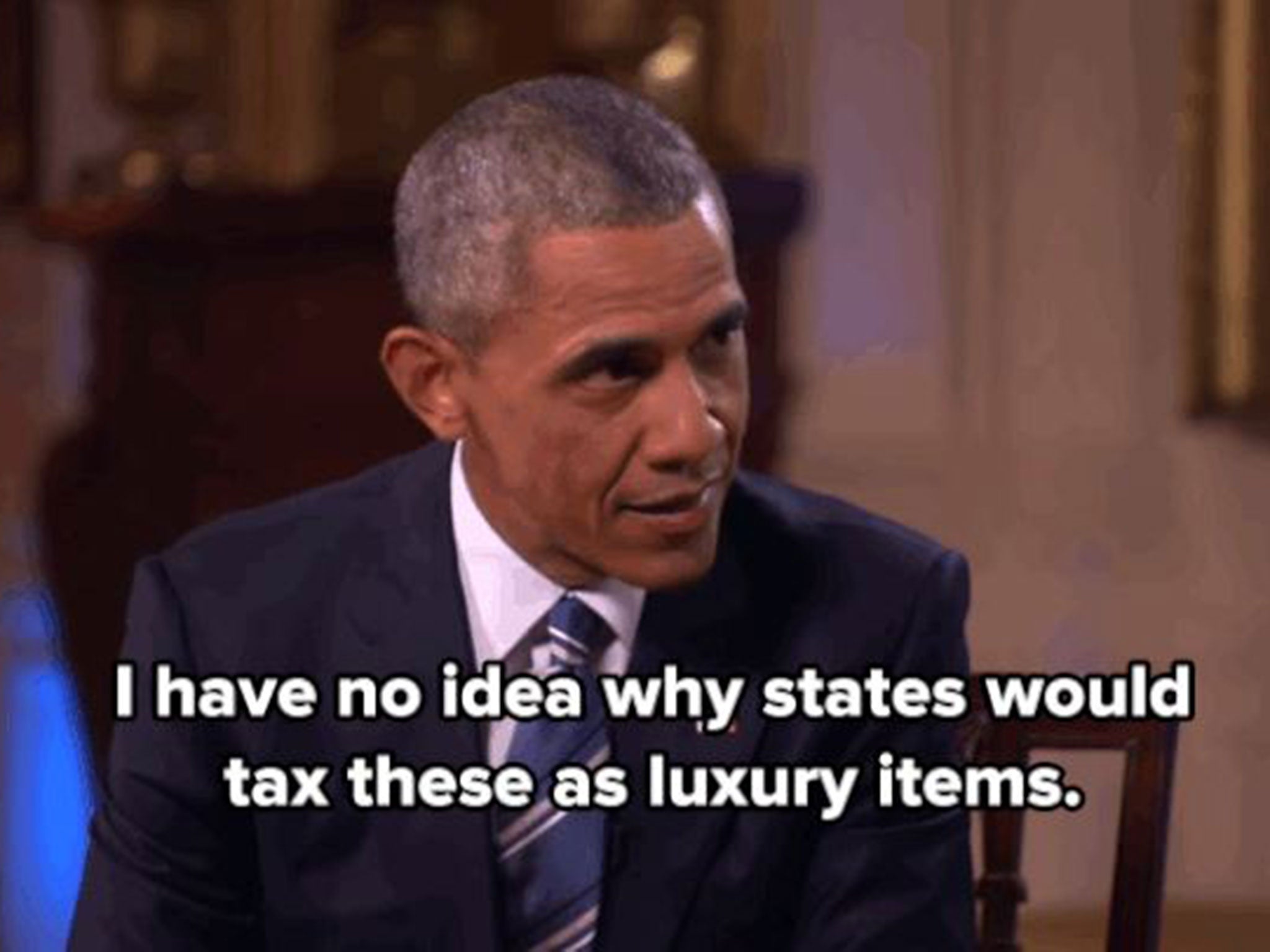

In January, Barack Obama may have become the first US president to discuss menstruation when 27-year-old YouTube sensation Ingrid Nilsen asked him why tampons and pads are taxed as luxury items in 40 states. Obama was stunned. “I have to tell you, I have no idea why states would tax these as luxury items,” he said. “I suspect it’s because men were making the laws when those taxes were passed.”

Nilsen’s interview went viral, as has her frank approach to one of the most whispered-about issues in culture and politics: menstruation. “Something that affects people every single day the president didn’t know about! And it’s because it’s one of those things that just gets buried,” she said. “That’s a reflection of how women’s bodies are viewed even today by our government and society.”

Over the past year, a steady stream of pop culture moments propelled menstrual equity into the mainstream. Musician Kiran Gandhi ran the 2015 London Marathon without a pad or tampon, crossing the finish line with a large red stain between her legs. When artist Rupi Kaur posted a photo of herself on Instagram, fully clothed and with a stain on her pants and sheets, the image was “accidentally” taken down. Twice. Donald Trump spawned the hashtag #PeriodsAreNotAnInsult when he complained about tough questions from GOP debate moderator Megyn Kelly, saying she had “blood coming out of her wherever”. From awareness-raising hashtag campaigns (#TheHomelessPeriod, #HappyToBleed, #FreeTheTampons) to a Change.org petition to lift the tampon tax, to 20-year-old Arushi Dua asking Mark Zuckerberg to launch an “on my period” button on Facebook to help fight menstrual stigmas in India, periods are having a moment.

This movement has been so widespread that Whoopi Goldberg is now launching a line of medical marijuana products to ease menstrual cramps. And in Hollywood, Jennifer Lawrence answered the ubiquitous “Who are you wearing?” question with a story about menstruation, telling Harper’s Bazaar that she chose her red Dior gown for the 2016 Golden Globes because the show coincided with her period and she wanted something that was “loose at the front…. The other dress was really tight, and I’m not going to suck in my uterus.”

Before pads and tampons, women folded soft gauze or flannels and pinned them to their undergarments when they had their periods. All that changed in the 1920s with Kotex sanitary pads, although they were only a cosmetic improvement as they’d move, shift and chafe, rubbing women raw.

In 1931, a Denver physician named Earle Cleveland Haas invented the modern tampon and applicator. He also invented the diaphragm. Mainstream culture gradually embraced feminine care products, and women started using tampons more than pads. Feminists heralded the tampon as a liberator. “No one was thinking about safety hazards. They were just grateful to have a product that plugs it up, literally,” says Chris Bobel, president of the Society for Menstrual Cycle Research. It was only in fringe, arty circles that people were pushing boundaries on tampon etiquette; feminist artist Judy Chicago’s 1971 “Red Flag” captured a grainy, close-up shot of her pulling a bloody tampon out of her vagina. Many assumed they were looking at a bloody penis, proving her point about period taboos.

In 1975, Procter & Gamble began test-marketing a tea bag-shaped, super-absorbent tampon called Rely (tagline: “It even absorbs the worry”). They were made of synthetic materials and the key ingredient was carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), a compound that boosted absorption so much that the tampon could theoretically last for an entire period. Many heralded them as a fabulous new design, but others found Rely tampons painful to remove because they absorbed so much fluid that they ripped the internal walls of vaginal skin when pulled out. Another problem: the teeth at the tip of the plastic applicator sometimes cut women.

The Rely tampons were also potentially lethal: CMC and polyester in tampons dried out women’s vaginas, creating the ideal breeding ground for the toxin-producing bacteria staphylococcus aureus. In 1980, 890 cases of toxic shock syndrome (TSS) were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and 91 per cent of them were related to menstruation. Thirty-eight women died.

Other super-absorbent tampon brands were implicated in TSS health concerns, including Playtex and Tampax, but Rely was the only one recalled in September 1980. All tampon manufacturers faced lawsuits over TSS, but over 1,100 were levelled against Procter & Gamble.

In the 1980s and ’90s, the safety profile of tampons improved and the incidence of TSS plummeted, and while CMC was no longer used in tampons, an explosive 1995 Village Voice article revealed a new threat: dioxin, a carcinogen that’s “toxic to the immune system” and linked to birth defects, had been found in some commercial tampons. While the tampon industry reformed some bleaching practices to reduce the dioxin risk to trace levels, they are not required to disclose the ingredients in tampons and pads, which means we know more about where our clothes are made than we do about what women put inside their vaginas.

The average woman uses about 12,000 tampons in her lifetime, and that’s a conservative estimate, says Philip Tierno, a professor of microbiology at New York University School of Medicine, who was among the first to link TSS with the synthetic materials in tampons. Viscose rayon, which is made from sawdust, is still used in tampons. As Tierno puts it: “It turns out to be one of the best of the bad ingredients.”

“We don’t have good, reliable data that tells us whether the things we’re putting inside our body, in the most absorbent part of our body, for days at a time, are safe or not,” says Society for Menstrual Cycle Research’s Bobel. “It’s symptomatic of the silence around menstruation.”

Small companies such as Lola and Conscious Period offer women what “big business” doesn’t: transparency. Commercial tampons are made of some combination of cotton, rayon and synthetic fibres, but Lola tampons are made from 100 per cent natural cotton. “In the absence of real hard, current data, we’d rather put something that we understand in our bodies,” says Jordana Kier, who co-founded the company with Alex Friedman. Since launching last year, Lola has raised $4.2m and attracted tens of thousands of customers.

Conscious Period sells nontoxic, 100 per cent organic, hypoallergenic, biodegradable cotton tampons. Cotton is the third-most sprayed crop in the world, co-founder Margo Lang explains, but the organic cotton in Conscious Period’s tampons is free of chemicals, dyes and synthetics. “Not all women are susceptible to TSS, but they have to be aware that it’s a possibility with any tampon. I’d put my money on 100 per cent cotton,” says Tierno. “All-cotton provides the lowest risk, whether organic or nonorganic, but manufacturers refuse to go to all-cotton because they’d have to adjust all their machines.”

Enter Thinx, created by Miki Agrawal of the Center for Social Innovation, along with her twin sister, Radha, and their friend Antonia Saint Dunbar. Thinx look like they could be the latest style of Calvins, but they’re the high-tech, period-proof underwear. They absorb the blood from a woman’s period so she doesn’t have to wear a pad or tampon, except on her heaviest days, when an extra layer of protection is recommended.

Agrawal explains that her patented underwear are anti-microbial, moisture-wicking and leak-proof, keeping women feeling dry, and can absorb up to two tampons’ worth of blood. That means more comfort, fewer tampons and less pollution. “There are over 20 million combined tampon applicators, pads and menstrual products that end up in a landfill every year,” she says. Thinx come in six styles, are washable and reusable, and cost $24 to $38 a pair. The company donates a portion of every sale to the Uganda-based AfriPads, which teaches women to make and sell reusable pads. Agrawal is also launching Thinx Global Girls Clubs, which will give out subsidised menstrual products and teach health education, self-defence and entrepreneurship.

Agrawal came up with the idea in 2010, when she met a 12-year-old girl in South Africa. “I asked her why she wasn’t in school, and what she said to me completely changed my life. She said: ‘It’s my week of shame,’” Agrawal recalls. “The girl explained that when she gets her period, she stays home from school. ‘I tried using leaves and mud and plastic bags and old bits of mattresses and old rags. None of it worked, and eventually I just stopped going,’” says Agrawal.

“There’s a period problem in the first world and a period problem in the developing world. Why no innovation? Why is no one talking about it?”

Colombian-born Diana Sierra is waging her own fight for menstrual progress by designing underwear that directly responds to the needs of girls and women in developing countries. A couple of years ago, Sierra left her industrial design job at Panasonic when, surrounded by facial steams and massage machines, she realised she was designing “for the 10 per cent of people who can pay for this stuff. Ninety per cent of the population are worthy of good products, but they don’t have this income, so they’re not seen as a good market,” she says.

In 2014, she launched BeGirl, a design company that creates high-performance menstrual pads and underwear. She got the idea during a United Nations internship in rural Uganda, where she taught locals how to turn arts and crafts into businesses. “I had 12-year-old girls knocking on the door saying they wanted to be part of the workshop.”

A teacher explained why they weren’t in school – they were menstruating. Stunned, Sierra hacked sanitary pads using material from an umbrella and mosquito net. She knew girls in Uganda used pieces of cloth to absorb their period blood, so she built underwear with a leak-proof mesh pocket that can be filled with cloth or other clean materials.

Since last year, BeGirl has distributed more than 15,000 pairs of reusable underwear in Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, Malawi and 10 other countries. BeGirl underwear are bright and cheerful, and for each sale the company donates a pair to a girl in need. “You cannot assume that just because someone has low income, someone has low expectations or low aspirations,” she says. “It’s not just giving a girl a panty or pad. It’s giving knowledge so she can own her body and make informed decisions.”

While sifting through survey results from product pilot tests, Sierra found a dusty page from a girl in Mbola, Tanzania. Answering the question, “What do you like most about the menstrual pads?” the girl wrote that she was “so happy because she knew someone somewhere loved her”, Sierra recalls. “Because that person made something so beautiful that she was so proud to ‘be girl’.” And so the name of Sierra’s company was born. “Here you have a girl continents away telling you that something as simple as a sanitary pad is giving her a sense of dignity and pride,” she says.

Organic and all-natural cotton tampons shouldn’t be a first-world privilege, but they are, and the fight against tampon taxes, while worthy, doesn’t matter if tampons aren’t available where you live and your culture shuns menstruation. In many countries, periods are like curses. Girls and women cannot cook, touch the water supply or spend time in places of worship or public areas when they’re menstruating.

In Africa, one in 10 girls misses school during her period every month. Seventy per cent of girls in India have not heard about menstruation before getting their periods, and four in five girls in East Africa lack access to sanitary pads and related health education. In Nepal, some rural families still follow an ancient tradition called chaupadi, banishing girls and women to sheds when they have their period.

“Most girls learn about their periods the day their periods start,” says Chandra-Mouli of the WHO. He recounts a story he hears time after time: “I started having periods at school. Spotting on my clothes. Giggling in class. I didn’t know what was happening. My panties felt wet. My teacher made me wait in the staff room. I thought my insides were rotting. My mother came and wrapped me in a towel, took me home, put me in a bath and said, ‘You’re a woman now. Don’t go out and play with the boys.’”

These systemic issues won’t be solved with a pair of high-tech underwear. “I spent time in Uganda, Kenya and India shadowing organisations working to address these issues,” says Bobel of the Society for Menstrual Cycle Research. “They understand it’s a material solution that funders love, and it’s concrete and scalable. What’s not getting challenged is the actual culture of menstrual secrecy and shame.”

A man known as India’s Menstrual Man is chipping away at this problem. Arunachalam Muruganantham grew up in south India, the son of poor handloom weavers. In 1998, soon after marrying his wife, he realised she was using soiled cloths to manage her period. When she explained that she couldn’t afford to buy sanitary pads as well as milk for their family, he decided to do something.

For years, he experimented with materials and prototypes. He tried to convince his wife to test his products, then he asked local medical students, but they all refused, so Muruganantham tested the sanitary pads himself. He filled a rubber bladder with animal blood, attached a tube that led into his underwear, and spent five days wearing a pad. “The messy days, the lousy days, that wetness. My God, it’s unbelievable,” he said in his 2012 TEDx Bangalore talk.

After six years of research, he built a machine that makes sterilised sanitary napkins. Today, he has 2,500 machines in India and a few hundred across 17 other countries. His pads retail for 3 cents a packet, and the machines cost $2,500 each, both below market rates. In 2014, Muruganantham was named one of Time’s 100 most influential people in the world, and his machines have enabled women to launch their own businesses.

Swati Bedekar, a scientist from Gujarat, India, bought one of Muruganantham’s machines in 2010 after visiting desert communities and witnessing girls sitting on stones or pots filled with sand to catch the blood from their periods. She wanted to help them, but the women who used her machine complained that the foot pedal led to back pain. So Bedekar tweaked the machine, simplifying the process, altering the design of the pads and adding wings for comfort. Yet there was another barrier: In most Indian cities and villages, there are no regulations for waste disposal, and used sanitary products are often wrapped in paper or some kind of plastic and thrown out with the trash. Stray dogs often rummage through the waste, and some men worry that women might use the pads for black magic. Bedekar’s husband, Shyam, invented a terracotta incinerator that looks like a garden pot and could burn used pads discreetly, quickly and without electricity.

While much of the innovation in India focuses on small businesses, ZanaAfrica Foundation provides sanitary pads and reproductive health education to 10,000 girls across Kenya each year. In 2004, Kenya became the first country in the world to eliminate sales tax on menstrual products, but there is still much work to be done. “Menstruation contributes to one million adolescent girls in Kenya missing up to six weeks of school each year,” says Gina Reiss-Wilchins, CEO of ZanaAfrica Foundation. “They’re dropping out of school at two times the rate of boys starting at puberty.”

In March, the foundation’s social enterprise arm, ZanaAfrica Group, which manufactures menstrual products for girls and women in East Africa, received a four-year $2.6m grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to fund a ground-breaking study examining the impact of providing pads along with girl-centred reproductive health information.

“If every girl in Kenya finished secondary school, there would be a 46 per cent increase in the country’s GOP across her lifetime. There are so many barriers: poverty, abuse, child marriage, pregnancy. Getting your period should not be a barrier,” says Reiss-Wilchins. “We are a quiet little revolution.”

An extract from Newsweek Magazine

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks