Thanks, Brock. You gave us victims a voice

The individual victims of sexual assault mostly feel themselves unheard. But as rape survivor Winnie M Li reports, the Brock Turner case – and social media – have changed that forever

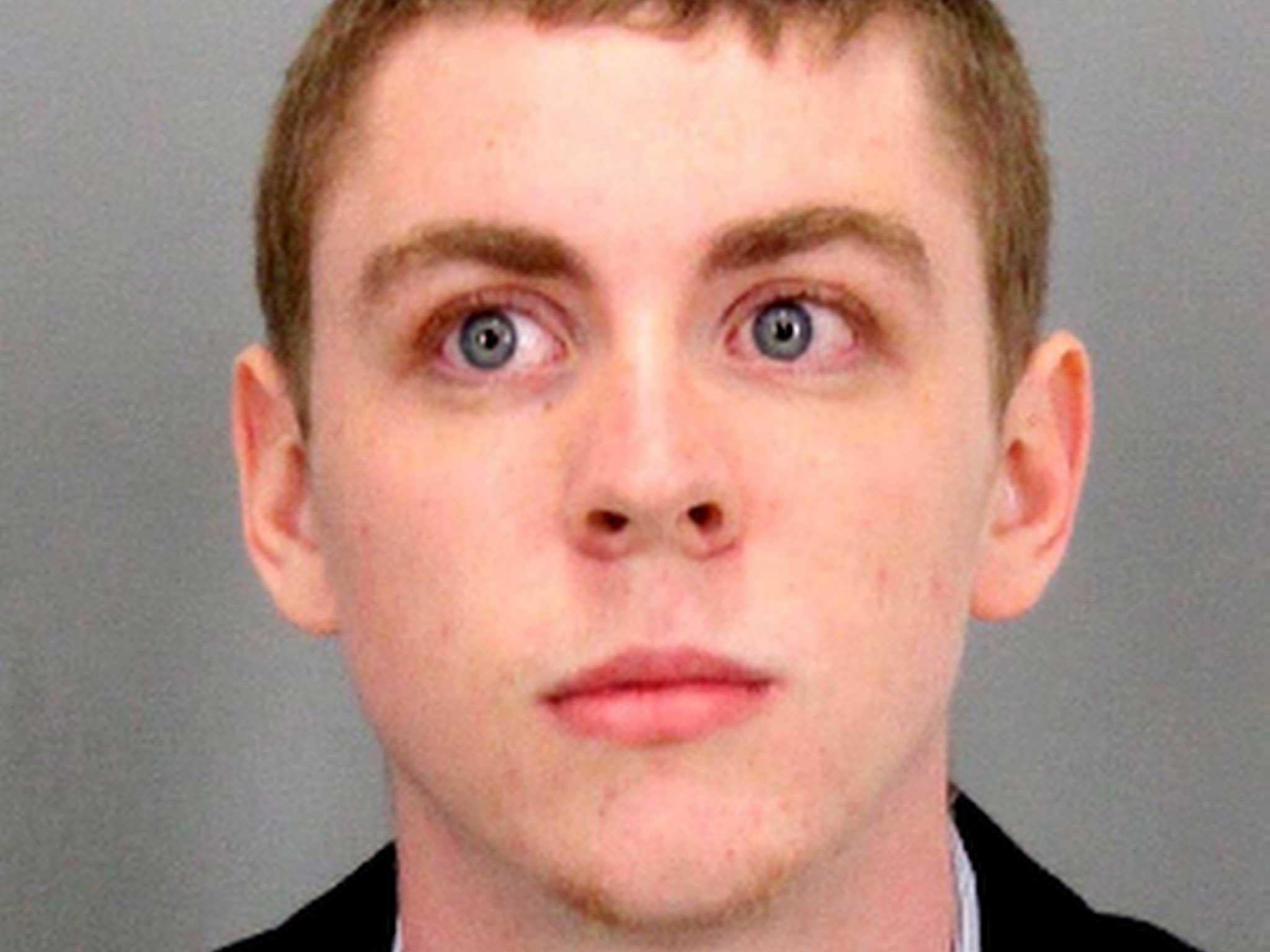

The internet has erupted in fury after the sentencing of Brock Turner, a star athlete for the Stanford University swimming team, who was convicted of three sexual offences, and more specifically of assaulting an unconscious, intoxicated 23-year-old woman behind a dumpster. Judge Aaron Persky only sentenced Turner to six months in county jail, noting that a harsher sentence would have a “severe” impact on him.

The victim’s court statement to Turner – a powerful, harrowing 12-page account of the impact the crime has had on her – went viral, with more than 13m views on Buzzfeed alone. So too, did a letter by Turner’s father, defending his son – lamenting how his life should not be ruined by “20 minutes of action”. A letter by Turner’s female friend, Leslie Rasmussen, was also released, claiming “rape on campuses isn’t always because people are rapists”. Cue further internet furore. Online campaigns to recall Judge Persky have earned over 500,000 signatures. Think pieces, blog posts, CNN videos, and spoofs by The Onion have been circulated and recirculated on social media, fuelled by vigorous discussions on Facebook and Twitter – marked by hashtags like #BrockTurner and #Stanfordrapevictim.

As a researcher studying the impact of social media on discussions about rape, I am watching a spectacular case study unfold in real time. As an activist, it feels like one case has finally sparked the conversation we need to have about sexual assault – a crime which affects millions of people. And as a rape survivor myself, it feels like for once, the victim’s voice is being publicly heard and valued. When my own rape took place eight years ago in Belfast, a much smaller scale media flurry ensued. Like the recent Stanford victim, I found myself Googling news stories on my assault, and felt the surreal displacement of reading what complete strangers were saying publicly about something very personal which had happened to me. And yet, nowhere in any of that coverage was there a place for myself, the victim, to speak.

Traditional media provides little platform for the victim’s side of the story to be heard. There is an assumption we are weak, ashamed, our lives ruined. And when there is the opportunity to speak, we are expected to summarise within a few soundbites, a brief interview, or a short number of words the enormity of an event that has changed our lives forever. Daytime talk shows and news programmes may provide exclusive interviews with “brave” survivors, but often these focus on the individual emotional suffering of their experience, without linking their case to larger systemic problems in how our society handles sexual assault. And yet, who else but the survivors can provide first-hand knowledge of the many ways in which our criminal justice systems, our educational institutions, and our public discourses fail to adequately address the reality of rape and sexual assault?

What is remarkable about the Stanford assault victim’s statement is that it was circulated uncut, at 7,244 words, and that it tells her whole story on her own terms. In so doing, it provides a poignant, elegant, undiminished account of the many small and big injustices rape survivors have to face on a daily basis. Despite its length, within the course of a few days, millions had read her statement and were continuing to share and comment on it. That is the power of social media. Unlike television, radio, or print journalism, there is no concern over column inches or expensive airtime, so individual writing can be expansive and more thorough. Social media can document the much longer term, often lifelong impact of rape on a survivor’s life.

It is clear from my own research, that social media allows readers to connect the dots, between their own experience and the ones they read about, which can be an important part of the healing process. And without social media, we may never have known about the many women who came forward with allegations against Bill Cosby. In the case of Brock Turner, social media has amplified the many thoughts of the public on all sides of the story. Feminists and rape survivors have been vocal in support of the victim, but so too, have “meninists” and rape apologists in undermining her claims. Likewise, we are hearing from legal scholars and racial inequality activists, comparing Brock Turner’s sentence to those of black men unjustly imprisoned for rape or black men found guilty in similar circumstances.

Regardless of your own stance, these are all legitimate voices and the opinions of real people – the same people who might be serving on a jury, or reacting to a rape allegation and choosing to believe or ridicule it. These recent outpourings on social media have served as a barometer for what the general public actually thinks about rape. Due to its intersections on class, privilege, criminal justice, and elite institutions, this particular rape has ignited a widespread and furious debate – but one which, most importantly, has at its centre a “voice” from the victim herself. And in that sense, this case is a game changer.

This article was first published on The Conversation. Winnie M Li is a PhD researcher in the Department of Media and Communications at the London School of Economics

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks