How phantom smells can ruin lives

People who experience phantosmia – olfactory hallucinations – can be plagued with odours of faeces, smoke or chemicals, with some even resorting to surgery

Have you ever smelled odours other people can’t smell? If you have, you may have experienced phantosmia – the medical name for a smell hallucination.

Phantosmia odours are often foul; some people smell faeces or sewage, others describe smelling smoke or chemicals. These episodes can be sparked by a loud noise or change in the flow of air entering your nostrils.

Spookily, some people seem to have a premonition that they are going to happen. The first time they occur, the phantom smell can linger for a few minutes, and the episodes may repeat daily, weekly or monthly for up to a year.

Since our sense of smell dominates the flavour of food in our mouth, any food consumed during a phantosmic episode will be tainted with the properties of the phantom odour. It is easy to see how these symptoms can severely affect a person’s quality of life. In extreme cases, it can even induce suicidal thoughts.

Related conditions

People with phantosmia often also report a closely related condition known as “parosmia”. This is where an actual smell is perceived as something quite different, such as the smell of a rose being perceived as cinnamon, although it is more often perceived as something unpleasant.

Both phantosmia and parosmia are known as “qualitative olfactory disorders” in that it is the perceived quality of the odour that has changed. In contrast, quantitative disorders are where the strength of the odour has changed and include conditions such as anosmia (loss of sense of smell) and hyperosmia (enhanced sense of smell to an abnormal level). Quantitative conditions can be measured using an objective standardised test.

It is rare for someone to experience phantosmia without some other existing quantitative condition, such as anosmia. And, interestingly, phantosmias often occur in the nostril with the least sense of smell.

Who gets it?

Usually, the first experience of phantosmia happens between 15 and 30 years of age with females more likely to be affected. It has been found in a number of different patient populations, including those with depression, migraine, epilepsy and schizophrenia.

Rates for phantosmia vary widely – from 0.8 to 25 per cent – being much higher for those people with existing olfactory conditions.

We don’t know what causes phantosmia, but it is thought to originate either from the central brain areas, including those that control emotion, or the peripheral areas more related to smell function, such as those areas involved in detecting odours.

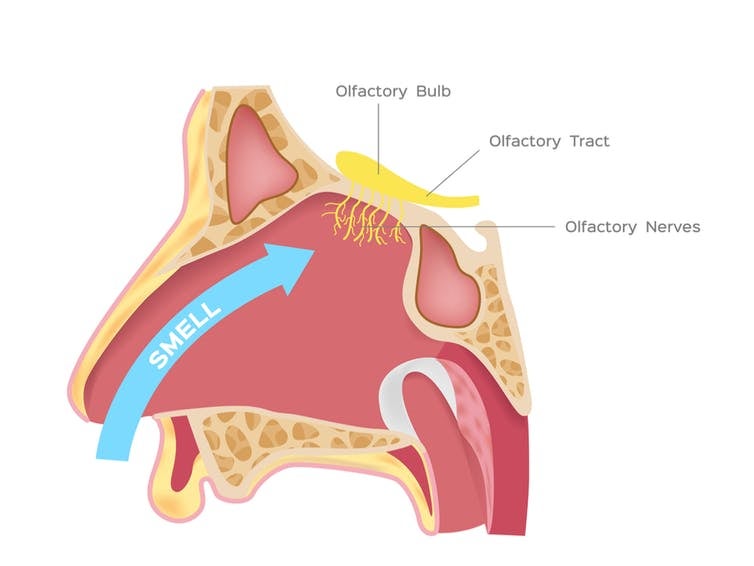

Some people find that administering saline drops to the nose can alleviate phantosmia, as can drugs used to treat existing neurological conditions, such as antidepressants and anti-epileptic medication. In extreme situations, and only after extensive medical consultation, some patients have the offending olfactory bulb (we have one for each nostril – see illustration above) removed by surgery, but this is a very risky procedure and would lead to permanent loss of smell for that nostril. Fortunately, though, phantosmia usually resolves on its own without the need for treatment.

If you start to smell odours that others can’t, you might wish to consult your GP, if only to rule out serious underlying disorders that may be causing the phantom smell. But just remember that in the vast majority of cases, phantosmia is a harmless condition rather than a sign of a serious underlying condition.

Lorenzo Stafford is a senior lecturer at the University of Portsmouth. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks