Man paralysed in both legs helped to walk again thanks to electrodes in his knees

The 26-year-old man was never expected to walk again following an accident five years ago

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A man paralysed in both legs from the waist down has been able to walk again with the help of a device worn on his scalp that collected electrical activity in his brain and sent the signals to his knees.

It is believed to be the first time that anyone with paraplegia due to spinal injury has walked several paces under the control of their own brain and leg muscles, scientists said.

The 26-year-old man was never expected to walk again following an accident five years ago that damaged his spinal cord and blocked the nerve impulses between his brain and legs which are needed for walking.

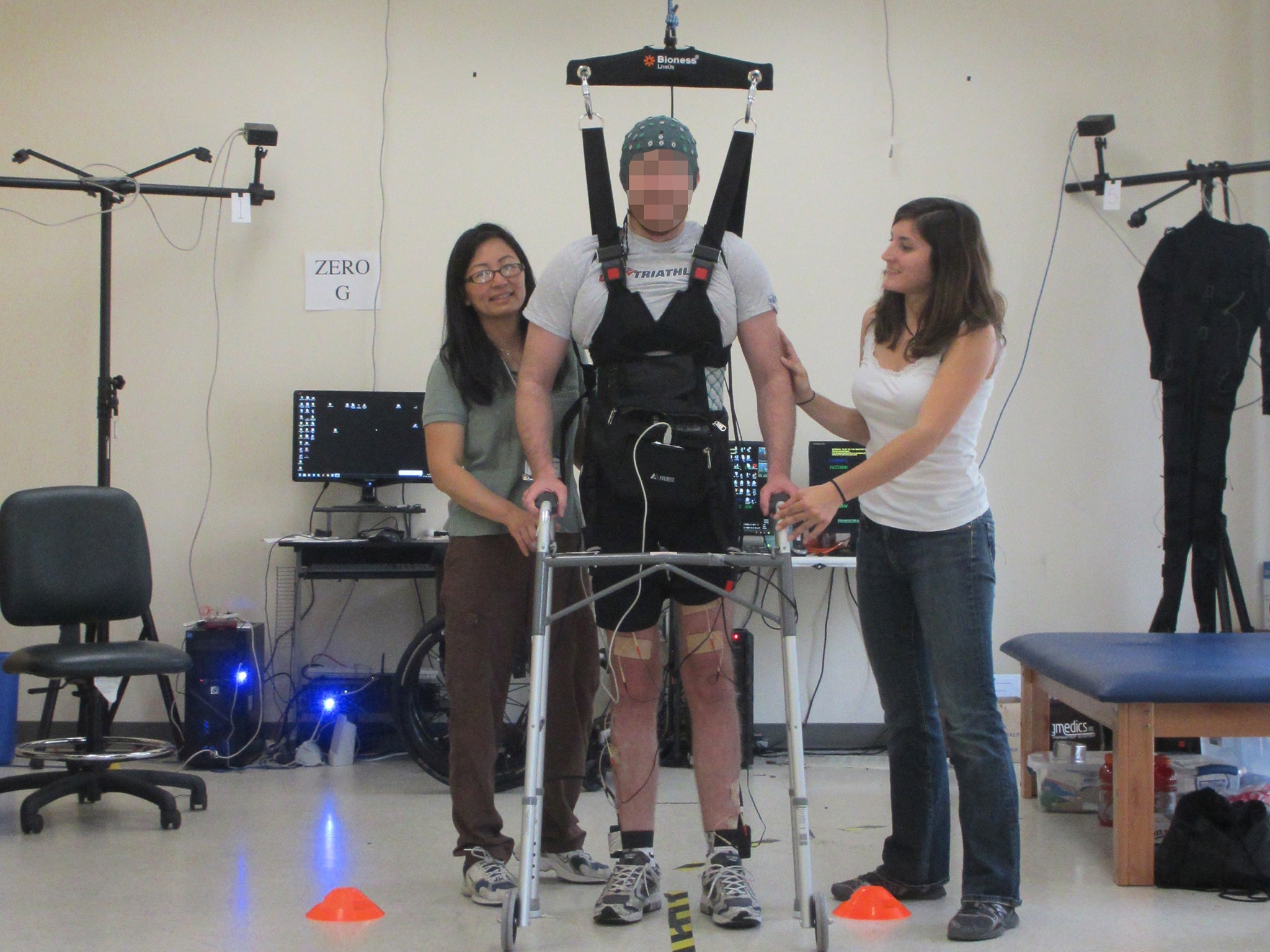

Researchers said that the achievement marks an important breakthrough in treating paralysis even though the man was only able to walk along a 3.66 metre course with most of his weight supported by a body sling.

“We have demonstrated that a person with paraplegia, or the inability to walk, due to spinal cord injury was able to walk over-ground by utilizing a brain-controlled, leg-muscle stimulator system,” said Zoran Nenadic of the University of California, Irvine, the senior researcher on the project.

“This proof-of-concept study demonstrates that it is possible to reconnect the brain and the muscle through a technology that bypasses the spinal cord injury,” Dr Nenadic said.

“It also shows that the brain signals that underlie the intentions to walk are still present in individuals years after an injury,” he added.

The patient wore a special cap that monitored the electrical signals around his brain and collected them as a computer-controlled electroencephalogram. The computer instantly sent the signals on to electrodes placed around his knees to stimulate muscle movements.

In the first part of the experiment the man trained on a virtual-reality system depicting a person on a computer screen whose walking could be controlled by thought alone.

Once the patient has mastered this virtual walking, the next stage was to train him to use his own leg muscles for simulated walking while he was supported with his feet 5cm above the training course.

The final stage involved him standing and walking on the ground using his own legs. with his body partially supported by a walking frame and body sling to prevent falls, according to the study published in the on-line Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation.

The scientists said that the test demonstrated the ability of the human brain to maintain its ability to send commands to the legs even after a serious injury to the spinal cord has blocked normal nerve communication with the lower body.

“Even after years of paralysis the brain can still generate robust brain waves that can be harnessed to enable basic walking. We showed that you can restore intuitive, brain-controlled walking after a complete spinal cord injury,” said An Do of the University of California, Irvine.

The electrodes that capture the encephalogram activity of the brain in the scalp cap did not penetrate the skin, but they could in future be developed as a more permanent implant if the technology can be improved and shown to work for other patients, Dr Nenadic said.

“We are in the process of designing an implantable version of the system that can yield brain signals of higher quality and thus facilitate more accurate control. The implant could also be used to deliver sensory feedback to the brain, so that the subjects could feel their legs as they are walking,” he said.

“We hope that an implant could achieve an even greater level of prosthesis control because brain waves are recorded with higher quality,” he added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments