I get knocked back, but I get up again: my journey with dyspraxia

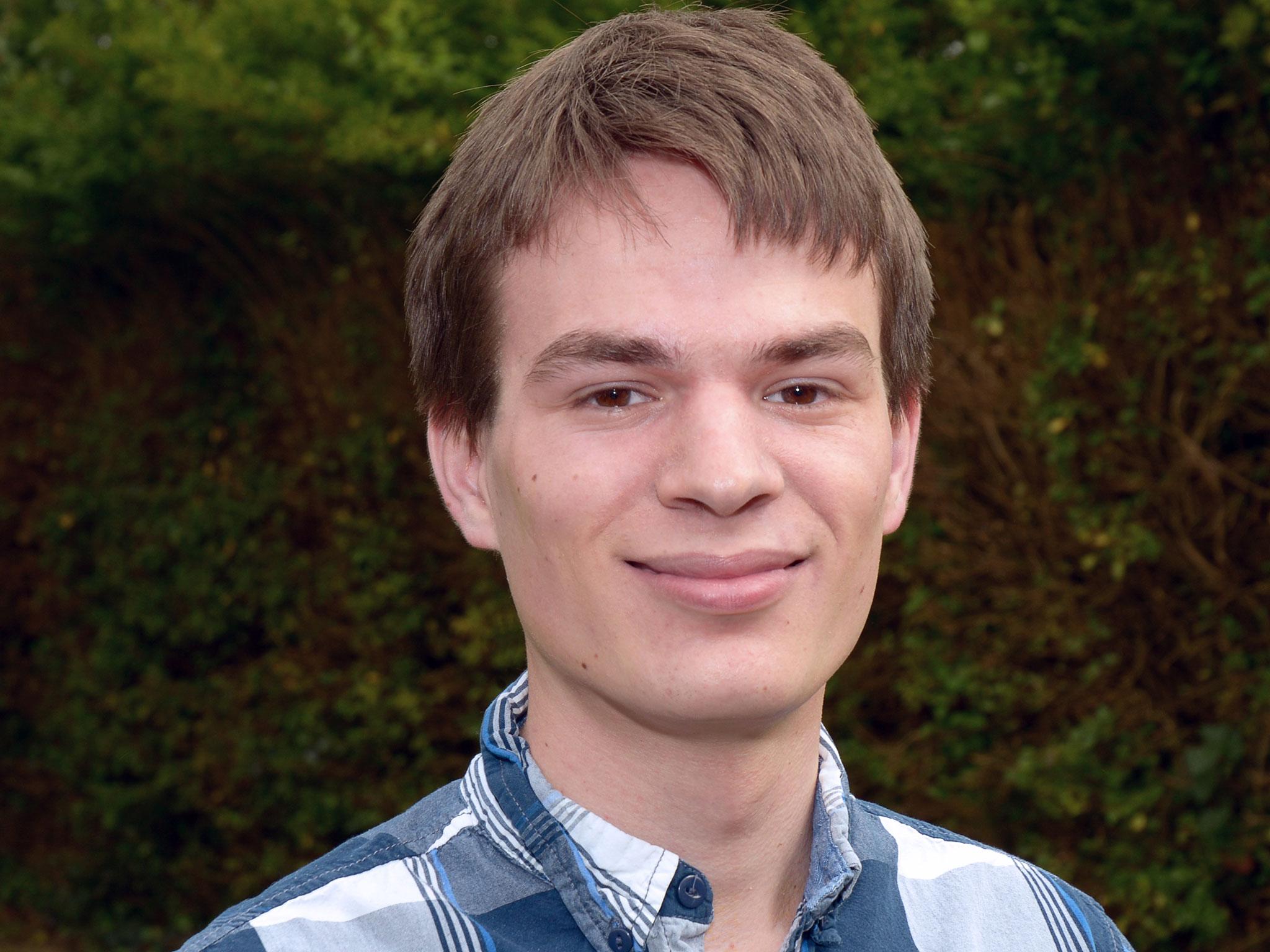

At the age of 18 Jake Borrett was diagnosed with dyspraxia, a condition that causes problems with coordination and speech, although sufferers are also known for their determination, creativity and empathy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Back in September 2012 I attended a disability meeting at my local university regarding my Crohn’s disease. When I went to sign a form, the disability adviser noticed the way I was gripping my pen. In passing, she mentioned this could be a possible indication of dyspraxia, a form of developmental coordination disorder, whereby the pathways for signals from the brain to the body get tangled up like a bunch of wires behind an old stereo system.

It was not until March 2013 that I decided to follow up her observation. And after rigorous assessments with an educational psychologist, at the age of 18 I was diagnosed with dyspraxia. It’s a condition for which there is neither a cause nor a cure yet known, but it is recognised as a specific learning condition, and the symptoms are many and various.

At the “gross” motor level, these include poor balance, poor hand-eye coordination and a tendency to fall/trip/bump into things and people. At the “fine” level, they affect manual dexterity and manipulative skills such as using cutlery, writing, drawing and playing musical instruments. On top of that, we have poorly established hand dominance; speech and language problems; poor eye movement, which disrupts tracking and relocation; and the misinterpretation of sense perception (lack of awareness of body position, direction and time/speed/distance/weight).

But that’s not all. Learning, thought and memory problems mean difficulties in planning, organisation and concentration. We can find it hard to judge emotion and behaviour from tone and non-verbal signals. And we can experience floods of emotion ourselves, from stress, anxiety and depression to emotional outbursts. People with dyspraxia vary in how their difficulties present themselves, and these may change over time depending on environment and life experiences. Some are often present throughout childhood, as were mine. I was a clumsy and hyperactive child, but we never put a name to it.

These days, I have issues with motor coordination skills, from learning to drive on a manual car to doing up buttons. (Funnily enough, last week at The Independent a fellow colleague of mine noticed I had not buttoned up part of my shirt, which may have stayed that way for the rest of the day otherwise.) Another difficult area is social situations, a feature of dyspraxia rarely discussed in the media. I find being around new people a particular challenge – partly fearing I’ll do or say something “wrong” or misread a non-verbal signal (which is why I also dislike talking on the phone). Although fellow dyspraxics have told me they find being in large groups “daunting”, I prefer going out in larger groups so that I have more opportunity to blend into the background.

But that’s the downside of dyspraxia. People of all ages with this condition do have some wonderful attributes, whether determination, creativity or a deep empathy for others. And with the right strategies in place, many of them can overcome obstacles associated with coordination and speech. Take me. It’s not in my nature to boast, but I have recently graduated with a First Class honours in English Literature and Creative Writing – and, looking back on my journey with English, I cannot believe how far I have come.

At primary school I was well below average, and I remember spending hours with my mum at the kitchen table strategically learning words to put in my examination response. (One word in particular was “sumptuous”, and destiny would have it I had to describe a feast.) At secondary school I was achieving grades deemed as “very low”, so I had to take learning support lessons instead of French for three years. Still, the learning support department was amazing, as we spent thrice-weekly hour-long lessons on sentence structure and other literary, language and speaking skills. With enthusiastic teachers I started to enjoy the subject – and, as they say, the rest of history.

Or should that be: the rest is English? Whichever, there is increasing support given to people with dyspraxia to help manage in a host of situations. For example, I had a Disabled Students’ Allowance in place in time for the start of university. Thus, because of my dyspraxia and Crohn’s disease, I was entitled to ergonomic equipment and computer software. These respectively eased back pain and fatigue and helped me to organise and plan essays. I further had a Study Needs Agreement at the university – a contract between students, disability advisors and any member of staff who needs to made aware of the nature of the disability and any changes that need to be implemented. I was entitled to 25 per cent extra time and the use of a computer in examinations; as well as an excellent study skills tutor.

Others have also benefitted from special help. Hannah Dickerson, diagnosed at 21, notes: “My driving instructor teaches me things differently to other pupils because the way I process information is different.” And we all profit from the moral and physical support we get on Facebook and Twitter, with their many pages and groups dedicated to the condition. Best of all is the Dyspraxia Foundation, an amazing organisation supporting thousands of people alongside its mission to raise awareness and funds.

It all goes to show that life as a dyspraxic can still be fantastic.

dyspraxiafoundation.org.uk

jakeborrett.blogspot.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments