How has racial equality changed since the 1960s? 'It feels like we're going backwards.'

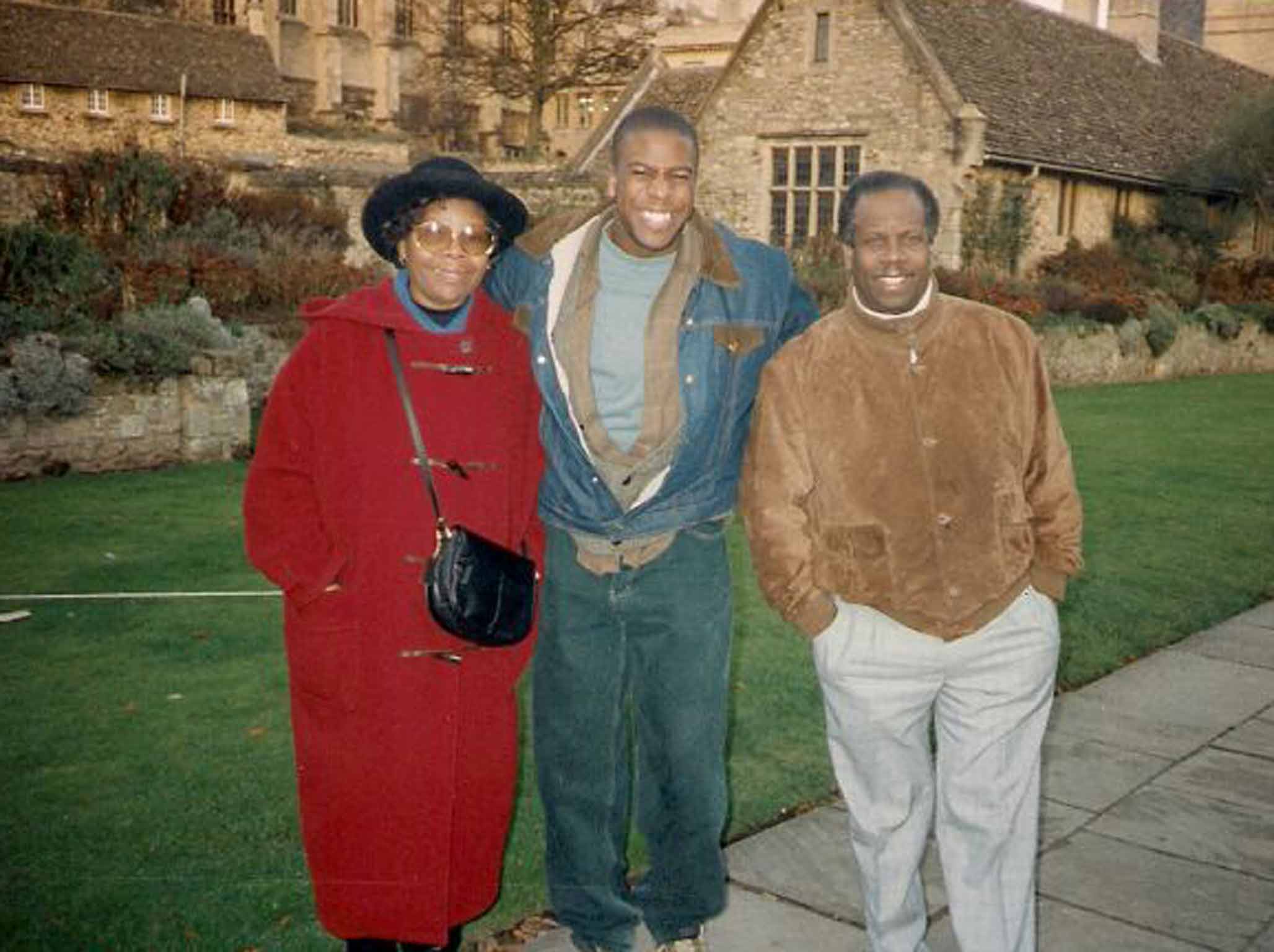

When the racial equality activist Rob Berkeley was asked to reflect on life in Britain for the black youth of today, he thought of his parents – who emigrated from Grenada in the 1960s and have now returned to the Caribbean –and wrote them this wry, moving and, at times, startling letter

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dearest Mum and Dad,

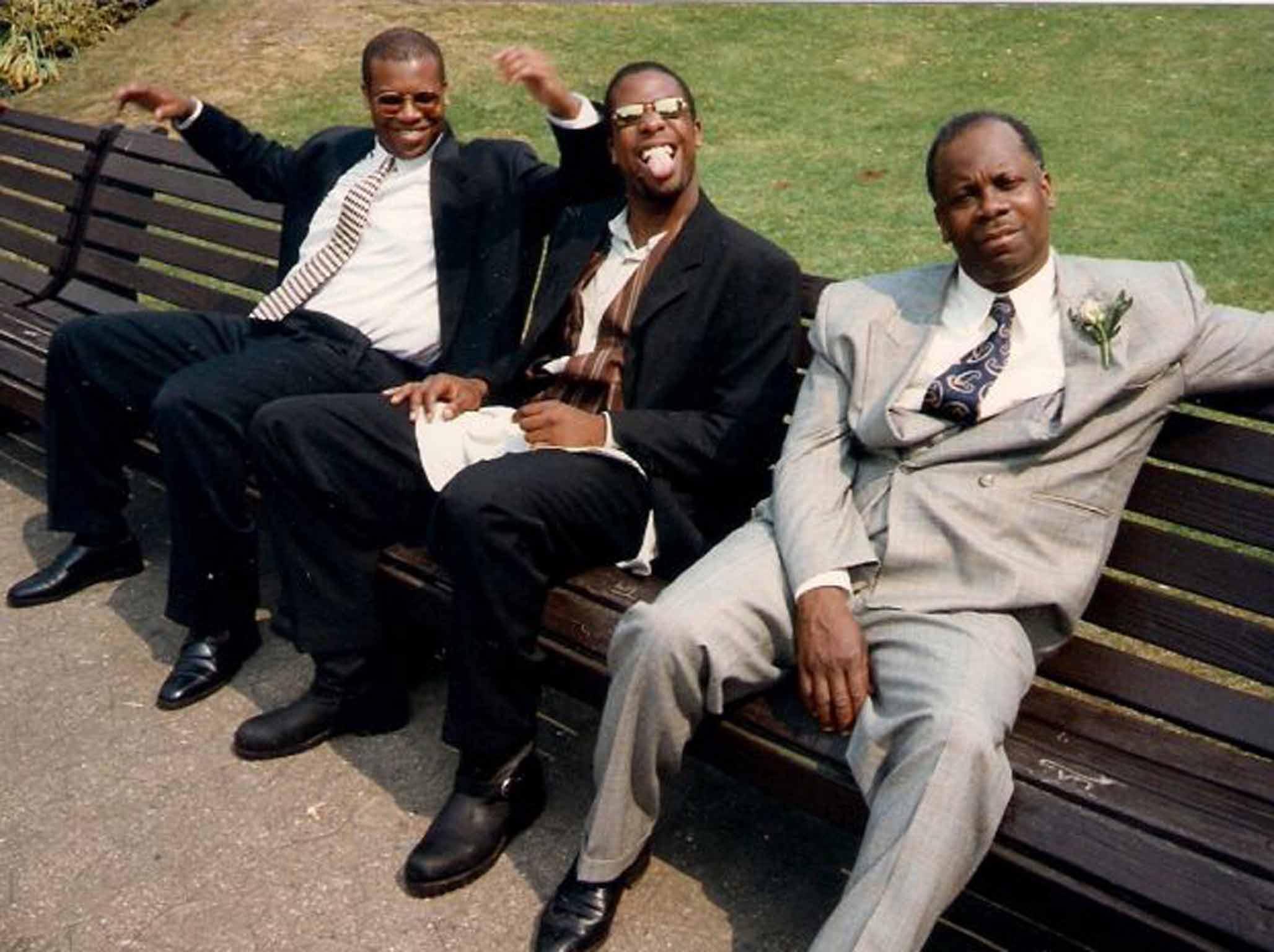

How are you doing? You know I've had a bit of time on my hands recently and I've been reflecting on the past few years of my career working on racial justice. You asked me about how things were going in the "struggle" and I was surprised how difficult that was to answer so I thought I'd try to write it down. When you and Dad retired back to Grenada 15 years ago after nearly 40 years raising the seven of us in London, you left us in good stead. We are a testament to your hard work in hard times. Your sons and daughters work as teachers, foster carers, a full-time dad, and even a tax collector. One of us even followed you into retail, Dad, though cars not fruit and veg.

A success story in so many ways and I know you are proud of us. If the migrant dream was a better life for you and your family, then your courage to move across the planet has paid off. We're doing well – unfortunately, some emerging research suggests that your grandkids' generation isn't doing as well as that of your kids'; progress seems to have stalled. I know you worry about what you have exposed us to – namely the racism that you faced and how we cope with it every day.

Your response to the daily microagressions of living in Britain as a black person was to build up our resilience. You taught us that the only way to respond to the discrimination that you assured us was inevitable was to be twice as good. That is why you invested so heavily in our education – sending us to extra lessons at the Saturday school and poring over our school reports for pointers about where we could improve – all this despite never having completed secondary education yourself. You learnt quickly that the teacher was not always right and did not always have our best interests at heart. I know that neither of you is a fan of confrontation but that did not stop you arguing our corner at school – especially when the PE teacher pushed us to do sport rather than maths, or when the careers teacher advised each of us to "downgrade our ambitions".

You were not alone in prioritising education. You'll be pleased to hear that last year black children, boys as well as girls, were among the fastest improving in our schools and had made progress in closing that achievement gap. It's not perfect yet though and black children still underperform in school – just not as badly as white children from poorer backgrounds. You'll be less pleased to hear that, as that gap has started to close, the Government and schools have taken their foot off the pedal and have cut support – somehow, I think they got the impression that improvements in GCSE results mean that the racism of low expectations has somehow disappeared rather than being the result of all those young people and their families working to be twice as good. I think they think that because the figures are moving in the right direction we can leave the rest to chance. Targeted action worked but the penalty for success seems to be withdrawal of support. This is despite black kids still being the most likely to be excluded from school for behaviour that others seem to be able to get away with.

There is worse news, though. It seems as if all that effort is not paying off. For black young people, improved exam results are not translating into improved jobs. While they are more likely to go to university, black graduates are three times more likely than their white counterparts to be underemployed. As students, they are clustered in institutions that employers do not value highly. I know you were aware of how atypical an experience I had at Oxford as one of only 16 black Caribbean heritage undergraduates in 1996. In 2009, that number had shrunk to only one. Last year, despite public attention being given to this problem, there were still only 14. In response to the scrutiny, the university stopped publishing the figures, rather than engage in how to change them.

These are tough economic times and I remember that Dad would tell me that once full employment began to disappear in the 1970s, black people were the first to be made redundant (last in, first out). Black youth now, especially the boys, are going through similar travails; 20 per cent of young white people looking for work cannot find a job but nearly 50 per cent of young black people are in a similar predicament. Dad, you would often be quite sanguine about it. "It's their country, after all," you'd say. I guess it's why you decided to be your own boss. Imagine what it is like for these young men – Britain couldn't be any more their country. Most of them have parents and even grandparents who were born here. Socially, we are not nearly as separated as we were in the past – our friendship groups, partners and children are often from a mix of ethnic backgrounds. One in every eight households in England and Wales is made up of people with different ethnicities. Nonetheless, "those who have shall have" seems to be the mantra – banks are reluctant to lend, so starting up businesses without the networks and know-how to do so and the bank of mum and dad to fall back on is a massive challenge.

The thing is that when you left I could point to a burgeoning black British culture – something not Caribbean or African, but British and black. I used to get excited at seeing Soul II Soul exporting music to the US, or Lovers' Rock showing JA a thing or two about reggae. Don't worry, we are still doing it – winning Oscars (I know Grenada is trying to claim that one, too!), providing HBO with great actors and all that. However, I don't feel like we are particularly well represented in front of or behind the camera here. I see arts organisations struggling even more to get funding to tell our stories and young people giving up on the BBC in favour of online entertainment; Channel 4 appears to be missing in action with regards to black communities. Makes me wonder why I pay my licence fee; makes me wonder whether there is more to arts than the opera, which you know kept its funding (actually went to the Royal Opera House for the first time the other day to see Ballet Black – two sell-out shows, brilliant work, white audience). It just seems that we are back to some kind of official canon of what is valuable and what is not – and what is seen as valuable is white.

When opportunities are not distributed fairly, it is understandable that this causes resentment and disengagement. My generation has a lot less trust in our politicians than yours did and those younger than me are even more turned off. It is a sad indictment on our politics that the greater the experience of our political system black people have, the less they trust in it.

The reality is that black people are less likely to be registered to vote and less likely to feel that they have an influence by the second generation. We undertook some polling and the gap between the issues that black people thought were important and those that white people thought important was pretty huge. You always told us that if we are not part of the solution, we are part of the problem; I worry that many black people have given up trying to make the system work and are opting out. What is clear is that those in positions of power are no longer listening to them.

I've found that when you raise issues about prejudice and discrimination, people turn off. Three-quarters of black people think that the Government should do more to tackle discrimination, but fewer than one in five white people agrees. Instead, we are told that racism is a thing of the past and will disappear over time. I've even been told to stop drawing attention to my ethnic background, that doing so makes me a racist. Yet survey after survey highlights persistent patterns of discrimination, and they are consistently ignored. Our surname is pretty English sounding but if we had an identifiably African surname, I'd have to make nearly twice as many job applications to even get an interview. I sometimes wonder what that means when I turn up to an interview – are they surprised; do they wish they could have screened me out earlier? You know me, though, I'd complain if I thought I was being treated unfairly.

This Government has made that harder and who would want to get a reputation for being a troublemaker? The Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) has gone now and we have a commission that is supposed to safeguard not just race but also gender, disability, sexual orientation and religion, all with a smaller budget than the CRE had! No wonder no one seems to be being held accountable, and no one in Government listens. You'll laugh when I tell you that a few months ago the BBC did a sting on letting agents who agreed to not let homes to black people on behalf of landlords – sound familiar? Absolutely nothing has been done as a result. Also sound familiar?

Good news, though – nobody is racist any more. Or that is what our media would have us believe. We've just been through an election campaign where the UK Independence Party (Ukip) leader was allowed to start almost every statement with "I'm not racist, but..." without challenge. As you always said, Mum, everything before the "but" is a lie! I no longer understand what you have to do to be called a racist, or what views you have to hold. A survey in May highlighted that more people describe themselves as "racially prejudiced" than at any time since you left. I appreciate that progress can be slow but it feels like we are going backwards.

When you and Dad came over you talked about how you had to build relationships with white people. However, you also talked about having to build relationships with people from other parts of the West Indies, Irish immigrants and meeting Africans for the first time. The past few years have been marked in my mind with an increasing distance between migrants from different places. This is perhaps a failing in policy which still sees integration as only a function of relationships between white and non-white people – we know that it's more complex than that. Ukip made progress by arguing that even black people were concerned about new immigrants. It appears that we've lost the ability to build solidarity between migrants and between them and the children of migrants. As one participant at a recent Runnymede event noted, "being British is when you are settled enough to be racist to newcomers".

Mum, you used to say that you had good kids because none of us brought the police to your door. The few interactions we had with the police were pretty harrowing, either when we were burgled and they were useless, or when they reduced my sister to tears by forcing their way into the house for a search while she was babysitting me; they suspected that "one of your lot" committed a mugging nearby. Can't say that things have improved that much – guess we all still look alike to them (I say, "them" because there still aren't very many black police officers). You are still three times more likely to be stopped and searched if you are black than if you are white – we've known about this problem for more than 30 years but the Home Secretary appears to have only just noticed and given the police yet another chance to get this right.

It's still true that at every stage of the system black people are likely to be judged more harshly. Instead of stepping up scrutiny, the Government has reduced reporting – I guess this makes sense if nothing is changing; I was getting depressed reading the same figures annually in any case. The scandals keep on happening and they make me embarrassed to be British – black deaths in custody going unpunished, shootings by the police which the system seems to collude with, senior black policemen retiring early each with a parting shot at the racism they faced on the job – from colleagues, not the public.

And, unfortunately, we need the police. Dad, I remember you and my older brothers telling me about the fear of routine violence from thugs in the street – teddy boys, skinheads, anyone! There were areas where no sensible black person would go. It's great that this has decreased but our young men are still not safe on the streets – 1,000 under-25s were stabbed or shot in London last year, according to the ambulance service. The police estimate that three-quarters of those on their register of young people at risk of serious youth violence are black.

I'd hate you to think that no black people are doing well in the middle of this mess. Some are doing very well – sports, business, fashion, arts; all have black faces near or at the top. It seems even more disappointing how rarely people in these positions feel able to talk about the racism they have faced and that so many still face. I often rationalise it by noting the lack of support we give each other when we do speak out and the need for the high achiever not to rock the boat too much. Perhaps also they do not see racism any longer or are working against it in ways that I don't understand. I wish that there could be a way of building solidarity between them and with those organisations working on public policy and at the grass roots so that they (should that be we?) could take concerted action to change these patterns.

Racism is complex and affects men differently than women, interacts with class to produce different forms, and I now get different reactions to me than I did when I was younger. I don't expect us all to agree about how to tackle such a difficult issue and suspect that different approaches will be required; but I'd like to think we could all agree that it does need to be tackled. I'd also hate you to think that the UK is not a great place to live, black or white – for me, Grenada's great for a visit but I'm staying here. I'd miss the buzz of London too much and hate the buzz of the mosquitoes.

You two taught us to be pragmatic but to never give up on our dreams. I still dream that one day "Croydon" will be enough of an answer to the question: "Where are you from?" I dream that one day I'll be judged on the content of my character rather than the colour of my skin. The pragmatist in me knows that this may be a little way off but that I can work to make tomorrow better than today. I'm also an optimist (thanks for that – I blame you both!) and think that if we are going to make progress on racial justice, we are better placed now than we have been at any time in the past.

The biggest change over time has been that we are now part of the British and they are part of us – our families, our lives, our futures are inextricably bound; that's why the nationalists' call for repatriation is now met with laughter. There are some great minds around, with impressive strategic experience. There are people in positions of power, there are growing grass-roots movements and austerity is creating the possibilities for new solidarities. As the current Mayor of Chicago said: "A crisis is a terrible thing to waste." Our current adversity will lead to change – we've just got to do our best to take control of that change.

I'm coming to Grenada for Carnival next month; I can't wait. I need to let my hair down (OK, I know I don't have any) and recharge my batteries. There's a General Election next year and racial justice will feature in the campaign – demographics mean that it will have to. I'm up for doing what I can to ensure that, when racial justice features, we can offer responses that take us forwards rather than backwards. I'm hoping others will be alongside me but if not I'm committed to doing it anyway. You travelled half-way round the planet for a better life for your family. Some effort from me to complete the journey to equality for the next generation doesn't seem like that much to ask by comparison.

Your loving son, Rob

Dr Rob Berkeley is the former director of Runnymede Trust, the UK's leading independent race equality think-tank

This 'letter home' is part of a project run by Race on the Agenda (ROTA), the social policy organisation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments