How dogs could make children better readers

Poor literacy impacts a child’s life chances – but there may be a rather colourful solution

Issues around children learning to read are rarely out of the news. Which is hardly surprising – becoming a successful reader is of paramount importance in improving a child’s life chances.

Nor is it surprising that reading creates a virtuous circle: the more you read the better you become. But what may come as a surprise is that reading to dogs is gaining popularity as a way of addressing concerns about children’s reading.

There is a lot of research evidence indicating that children who read extensively have greater academic success. The UK Department for Education’s Reading for Pleasure report, published in 2012, highlights this widely established link.

Keith Stanovich, an internationally eminent US literacy scholar (now based in Canada) wrote a widely cited paper in 1986, describing this virtuous circle as the “Matthew effect” (a reference to the observations made by Jesus in the New Testament about the economic propensity for the rich to become richer and the poor, poorer).

A downward spiral impacts upon reading ability and then, according to Stanovich, on cognitive capability.

Underachievement in groups of children in the UK is recognised in international studies – and successive governments have sought to address the issues in a range of ways. Reading to dogs, so far, has not been among them, but it’s time to look at the strategy more seriously.

Many children naturally enjoy reading and need little encouragement, but if they are struggling their confidence can quickly diminish – and with it their motivation. This sets in motion the destructive cycle whereby reading ability fails to improve.

So how can dogs help?

A therapeutic presence

Reading to dogs is just that – encouraging children to read alongside a dog. The practice originated in the US in 1999 with the Reading Education Assistance Dogs (READ) scheme and initiatives of this type now extend to a number of countries. In the UK, for example, the Bark and Read scheme supported by the Kennel Club is meeting with considerable enthusiasm.

The presence of dogs has a calming effect on many people – hence their use in Pets as Therapy schemes (PAT). Many primary schools are becoming increasingly pressurised environments and children (like adults) generally do not respond well to such pressure. A dog creates an environment that immediately feels more relaxed and welcoming. Reading can be a solitary activity, but can also be a pleasurable, shared social event. Children who are struggling to read benefit from the simple pleasure of reading to a loyal, loving listener.

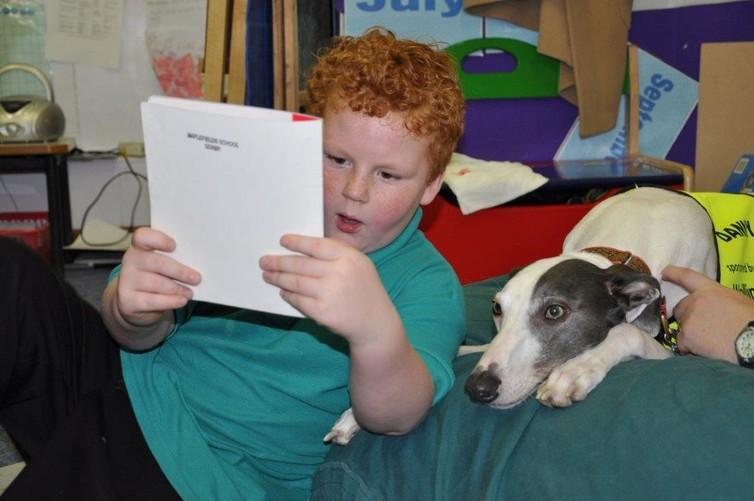

Children who are struggling to read, for whatever reason, need to build confidence and rediscover a motivation for reading. A dog is a reassuring, uncritical audience who will not mind if mistakes are made. Children can read to the dog, uninterrupted; comments will not be made. Errors can be addressed in other contexts at other times. For more experienced or capable readers, they can experiment with intonation and “voices”, knowing that the dog will respond positively – and building fluency further develops comprehension in readers.

For children who are struggling, reconnecting with the pleasure of reading is very important. As Marylyn Jager-Adams, a literacy scholar, noted in a seminal review of beginner reading in the US: “If we want children to learn to read well, we must find a way to induce them to read lots.”

Reading to a dog can create a helpful balance, supporting literacy activities which may seem less appealing to a child. Children with dyslexia, for example, need focused support to develop their understanding of the alphabetic code (how speech sounds correspond to spelling choices). But this needs to be balanced with activities which support independent reading and social enjoyment or the child can become demotivated.

Creating a virtuous circle

Breaking a negative cycle will inevitably lead to the creation of a virtuous circle – and sharing a good book with a dog enables children to apply their reading skills in a positive and enjoyable way.

Research evidence in this area is rather limited, despite the growing popularity of the scheme. A 2016 systematic review of 48 studies – “Children Reading to Dogs: A Systematic Review of the Literature” by Hall, Gee and Mills – demonstrated some evidence for improvement in reading, but the evidence was not strong. There clearly is more work to do, but interest in reading to dogs appears to have grown through the evidence of case studies.

The example, often cited in the media, is that of Tony Nevett and his greyhound Danny. Tony and Danny’s involvement in a number of schools has been transformative, not only in terms of reading but also in promoting general well-being and positive behaviour among children with a diverse range of needs.

So, reading to dogs could offer many benefits. As with any approach or intervention, it is not a panacea – but set within a language-rich literacy environment, there appears to be little to lose and much to gain.

Gill Johnson is an assistant professor in education at the University of Nottingham. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks