You can’t ask me that: Do you really want to live forever?

Continuing her series tackling socially unacceptable questions, Christine Manby asks if we should be trying to extend our life expectancy

Do you want to live forever? For the past century, it seems the chances you might have been increasing. There are more than seven times as many centenarians today than there were in the 1980s. Rudi Westendorp, professor of old-age medicine at the University of Copenhagen, recently suggested that a future 135-year-old had already been born.

We’ve long since breached the 120-year mark. That was with Jeanne Calment, who was 122 years and 164 days old when she died in 1997. Though Calment was deaf, blind and confined to a wheelchair, she said on the occasion of her final birthday, “I dream, I think, I go over my life, I never get bored.”

The French, it seems, are particularly good at living a long time. A baby born in France today has a one in two chance of hitting a century. Time to put cabernet sauvignon in the sippy cup? Alas, non.

While in 2016, life expectancy for the average Brit was 79.5 years for men and 83.1 years for women, it was estimated that more than 20 per cent of those years would be spent in ill health. But are we prepared to do what it takes to live that last fifth of our lives in fine fettle? What it does take, according to a study by Harvard University, is not smoking, keeping an eye on your weight, exercising for 30 minutes each day, having no more than one glass of wine daily (hold that cab sav) and eating healthily.

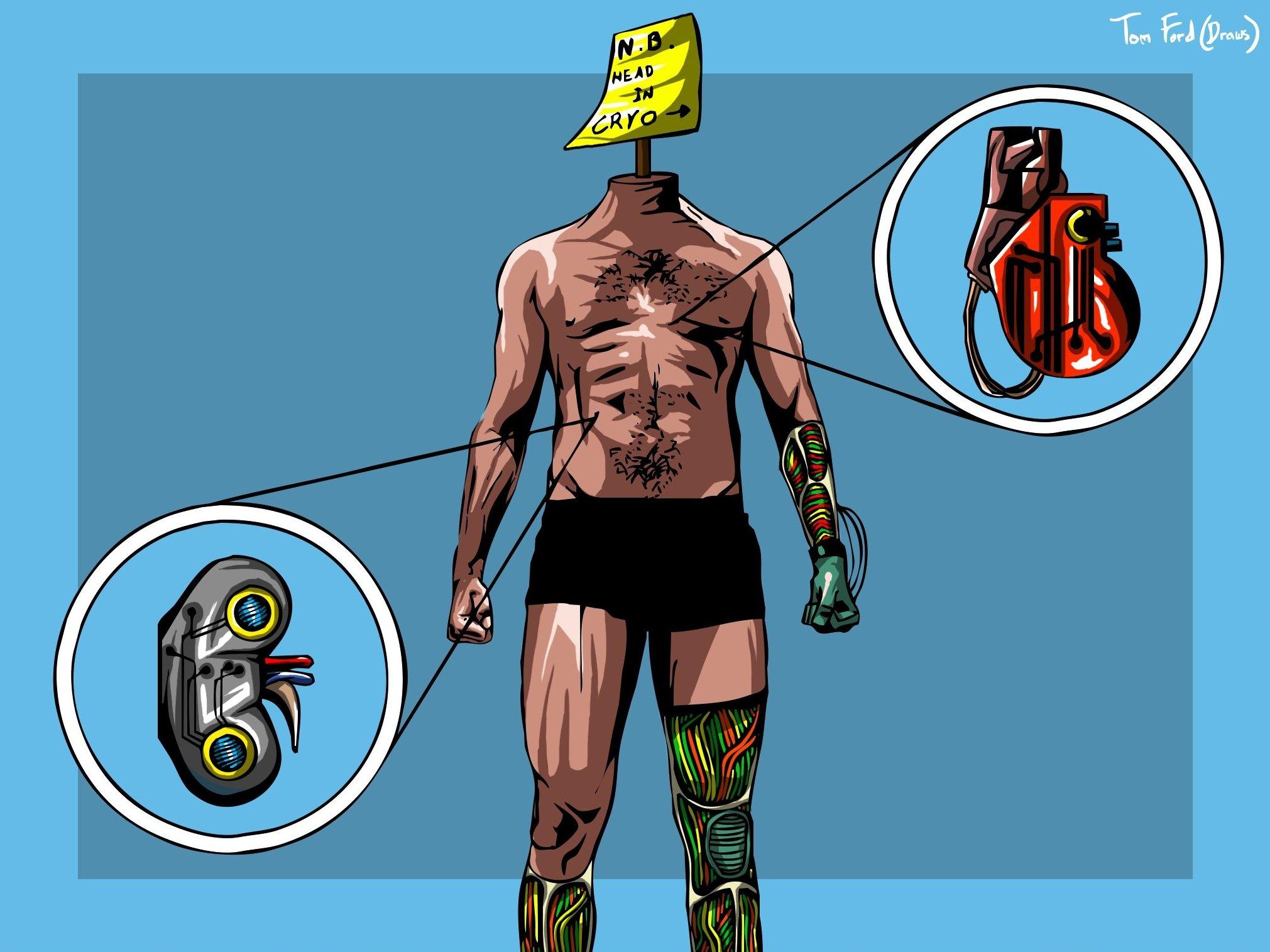

In Rachel Heng’s debut novel, Suicide Club, it’s not unusual for people to live to be 300 with the aid of technologically advanced “spare parts” and extreme dedication to healthy living. As Heng’s characters face a future in which immortality is a very real possibility, some of their number begin to question whether the sacrifices they must make in order to live forever are effectively draining life of all its meaning on the way. They can’t eat meat. They can’t run (too damaging for the joints). They can’t even listen to stirring music lest it raise their cortisol levels. For every advance in longevity there’s a sacrifice.

I asked Heng what she would be willing to give up for an extra decade. She replied: “I think if it were just one ‘vice’, rather than all the vices as in my novel, then there are many things I’d be willing to give up in exchange for a guaranteed extra 10 years in good health. Something I’d be willing to give up, and have already to some degree, is alcohol. I’d also probably be willing to give up caffeine and staying up late. Something I certainly would not want to give up is most foods – carbs, cheese, meat or chocolate.”

When it comes to the cosmetic treatments already available, Heng would avoid the lot. No Botox. No fillers. Not even tooth-whitening. “I’m terrified of needles and worry that teeth-whitening would lead to tooth sensitivity!”

Of course, Botox is already old hat, being edged out by injectable moisturisers in the form of gels made from hyaluronic acid that can hold several times its own weight in water. They’re available now at £900 a pop. Or you could “grow-your-own facelift’ with stem cells harvested from your own fat. The stem cells are reinjected into areas of your face that have been “lightly damaged” by laser. They jump into action to repair the laser damage and plump up your face in the process (I’m paraphrasing, of course). Why stop at your face? You can even use lasers to plump up a saggy vagina.

But all these procedures are in their infancy. If only one could wait another 20 years or so before trying these new-fangled methods. Just until we know for sure they won’t cause you to look like the Bride of Wildenstein. Perhaps you can. But you’ll have to die first. Cryonics is the process of flash-freezing a human body in liquid nitrogen in the hope of reanimating it at such a point in the future where we have found a cure for cancer/unsightly genitals.

A friend’s husband is planning to have his head frozen after death in the hope that one day he’ll be reanimated and able to return to his family. His children are young and he can’t bear the thought of not being there to see them grow up. Of course, if he were to die tomorrow, it would be wonderful to have him back next week. But while the technology for freezing the human body after death is there, the technology for reanimating those bodies is still a long way off.

Imagining a 50-year lag between dying and reanimation makes cryonics much less appealing. Would the kids be so thrilled to have Dad back then, looking younger than they do and insisting he still knows best despite having missed a half century’s worth of history? Personally, I think we should shuffle off when we’re supposed to and let the next generation have its turn unencumbered by undead in-laws.

I also think it’s a big mistake to rely on as yet unborn generations to bring you back to life. I can’t help but imagine a future world in which the earth has been colonised by aliens who view cryogenically frozen humans in the way we view fish fingers. With no guarantee that you won’t be defrosted in a frying pan, it seems like a waste of money to me. Everything that promises longevity without making the efforts that Harvard University suggested seems to cost an awful lot of money.

But when it comes down to it, surprisingly few people would take the immortality option anyway. In Ireland, AA’s life insurance team found that less than 20 per cent of the people they surveyed would choose eternal life if offered the opportunity. A 2013 survey by the Pew Centre for Research found that more than half of the American adults they questioned would not even want to live to 120. The Pew Centre suggested it’s because we still just don’t trust the science. Or want to make the sacrifices. As an eighty-something friend told me over a suitably boozy lunch: “If you give up smoking, drinking and sex, you won’t live longer. It will just feel like you are.”

In any case, Oxford University researchers have recently reported that for the first time in a very long time, life expectancy in the UK has gone into reverse. The first few months of this year saw a 13 per cent rise in death rates, possibly as a result of cuts to social care. Taken into consideration with rising death rates since 2015, OU says the figures are enough to justify a recalibration to show a drop in life expectancy of a whole year for those people heading into their forties and fifties now.

Live forever? You’ll be lucky. Perhaps that old Queen song had it right. “This world has only one sweet moment set aside for us.” Better make the most of it.

Christine Manby has written numerous novels including ‘The Worst Case Scenario Cookery Club’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks