How parasites and bacteria could be changing the way you think and feel

From losing inhibitions and anger to schizophrenia and dementia – science is uncovering the role small critters play in a range of illnesses and behaviours

Given recent events around the world, you could be forgiven for thinking that people have been acting in a very odd and unpredictable manner. There has been much research across psychology and economics to explain why we behave the way we do and to explore what our motivations may be. But what if there are other unseen influences at play? As science uncovers more about the influence of parasites and bacteria on human behaviour, we may well begin to see how they also shape our societies.

Mind control is a very real and prevalent threat to humans. We already know it is used by many organisms throughout the animal kingdom and how essential it is for the transmission and reproduction of many diverse parasitic species. The Cordyceps fungus, for example, infects ants before making them travel to the top of the tree canopy where they die. The fungus then reproduces and its offspring float down to the forest floor to infect more ants.

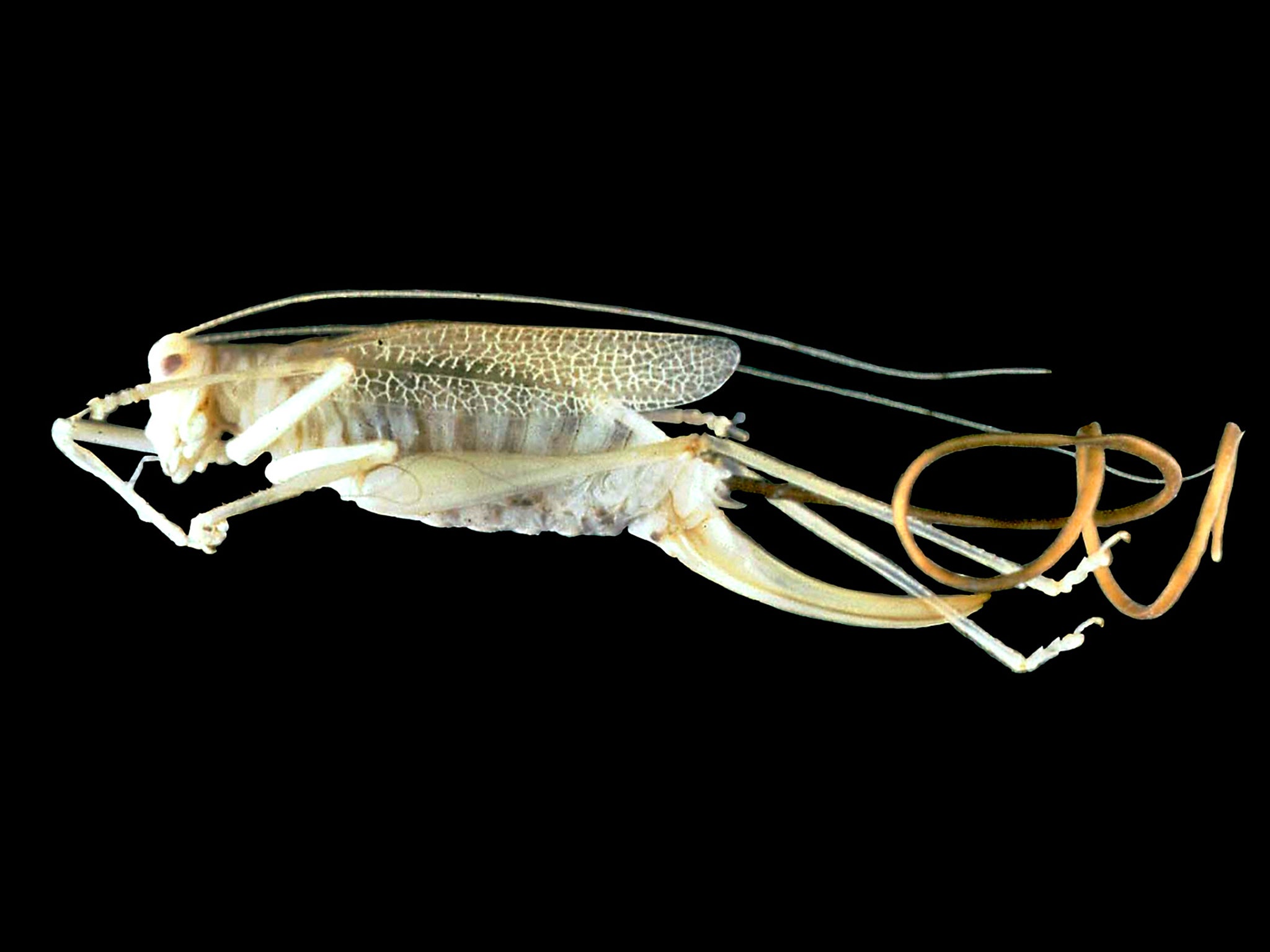

Nematomorph worms, meanwhile, make their cricket hosts die by suicide by jumping into water and drowning in order to get back to where they normally live. And parasitic trematodes infect snails so that their eyestalks bulge and change colour to red, blue and yellow. The next host, a bird, sees a juicy maggot and pecks off the eyestalks so the trematode can complete its lifecycle in the bird’s gut.

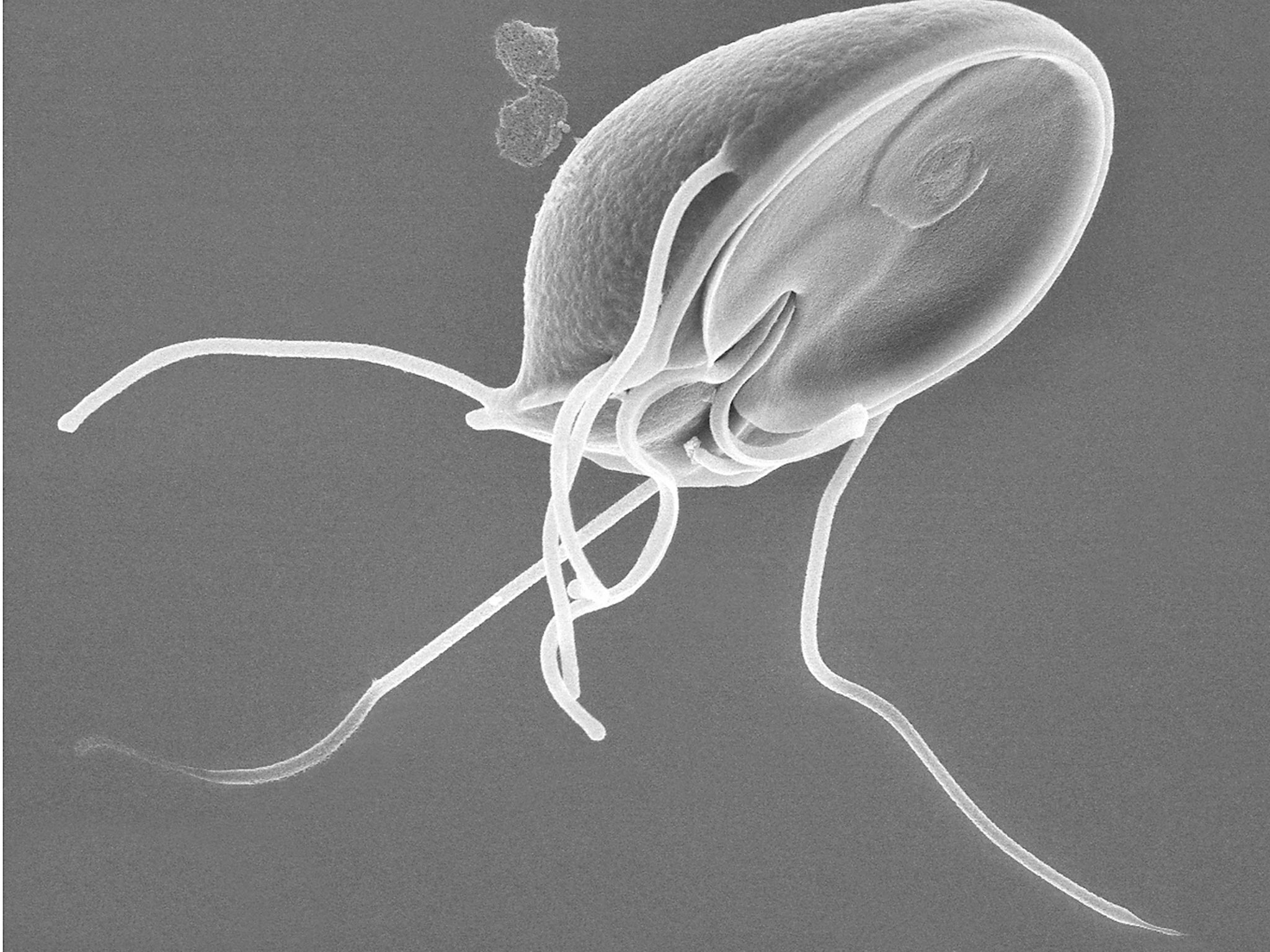

These horror stories are not restricted to invertebrates – and humans are not immune. When we learned how to farm and select strains of crops that grew best in certain environments, we sometimes made a surplus that could be stored for the future. This brought wild mice and rats and with them cats and a hidden danger: the protozoan parasite, Toxoplasma gondii.

This parasite can’t complete its lifecycle in humans, but we can be infected by it through coming into contact with cat faeces (or eating uncooked meat). The percentage of people estimated to be infected worldwide is between 30 and 40 per cent. France has an infection level of a staggering 81 per cent, Japan 7 per cent, and the US 20 per cent.

T gondii does strange things to rats and mice to make sure they come into contact with cats. They lose their inhibition of cats and cat urine. They become more exploratory and spend more time in daylight. But even stranger things happen when humans inadvertently come into contact with T gondii. Men are more likely to be in car crashes due to riskier behaviour. They also are more aggressive and more jealous.

Women, meanwhile, are more likely to commit suicide. It has even been suggested that T gondii could potentially be involved in dementia, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and autism. There is even evidence from more than 40 studies that people suffering from schizophrenia have elevated levels of IgG antibodies against T gondii.

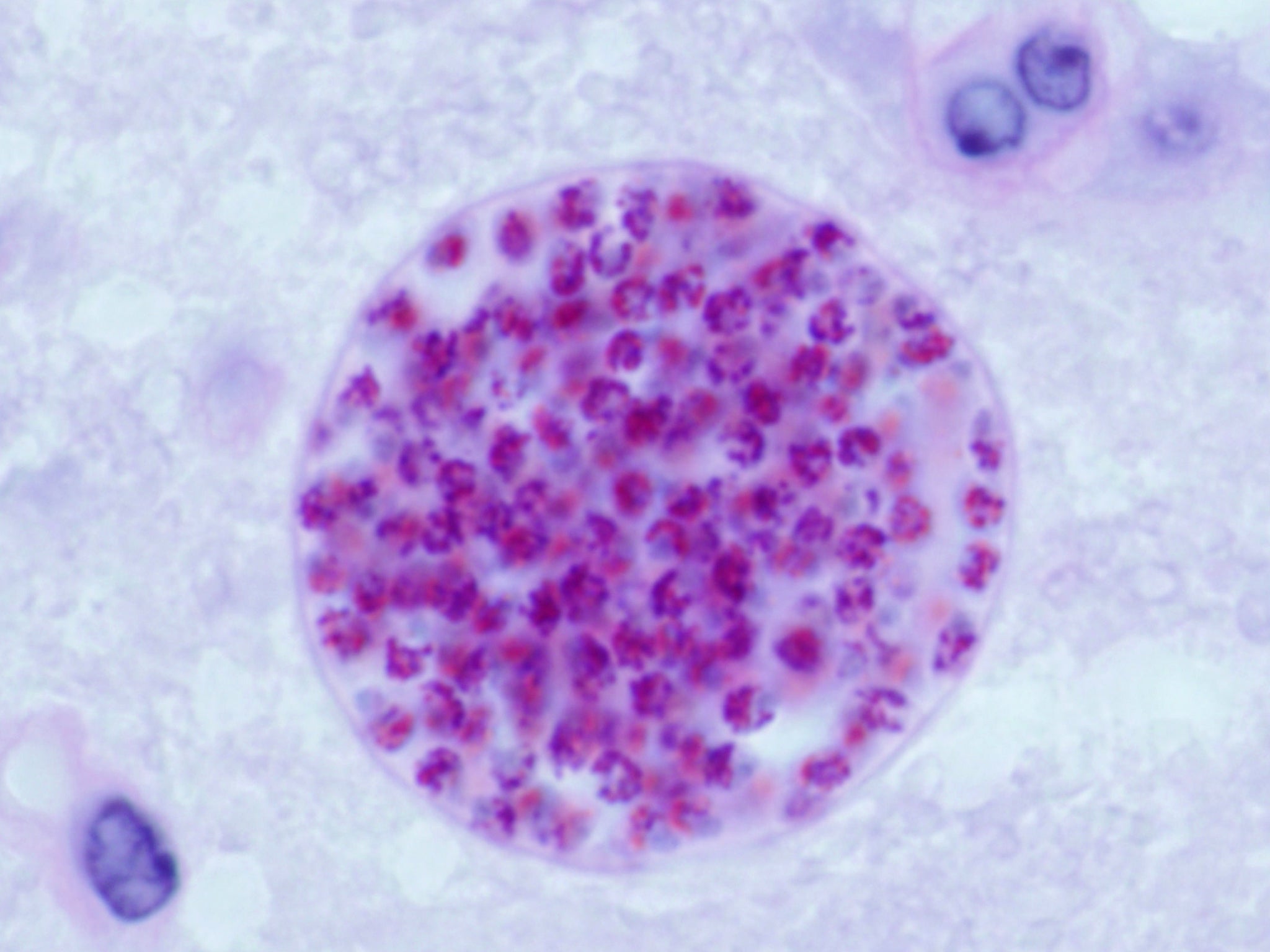

So how does this tiny organism cause such extreme reactions? The full answer is still to be discovered but there are tantalising results that show it influences the levels of neurotransmitters such as dopamine. Cysts (bradyzoites) are found throughout the infected brain in clumps or individually in specific places such as the amygdala, which has been shown to control fear response in rats.

Interestingly, an imbalance in dopamine levels is thought to be a characteristic of people that have schizophrenia. Analysis of the T gondii genome has discovered two genes that encode tyrosine hydroxylase, an enzyme that produces a precursor to making dopamine, called L-DOPA. And there is experimental evidence to support how this might go on to affect behaviour. Primarily, dopamine levels are high in infected mice and their T gondii-related behaviour can be reduced if the antagonist of dopamine (haloperidol) is administered.

Microbial mind controllers

There are many more mini puppet masters. It has recently been shown that the microbes that are plentiful on and in our bodies may also exert an influence on our behaviour.

We are covered in microbes and our human cells are outnumbered by bacterial cells eight to one. In fact, we are more microbe than human. This microbiome has been shown to regulate, not just the digestion and breakdown of food, but many different processes, too. Alterations to the gut microbiome can lead to susceptibility to conditions such as diabetes, neurological conditions, cancer and asthma.

But it was recently shown that the gut microbes that break down food can directly affect the production of another neurotransmitter (serotonin) in the colon and blood, which can then in turn affect communicative, anxiety-like and nerve-related (sensorimotor) behaviours. In the future, there may be the possibility of treating anxiety or depression by administering a “healthy” microbiome, and recent research altering the microbiomes of patients suffering from Clostridium infections has shown excellent results via faecal transplantation from healthy individuals.

With further research we will begin to unravel just how these microscopic overlords are manipulating our decisions – and their influence on society, culture and politics should not be underestimated.

Robbie Rae, lecturer in genetics, Liverpool John Moores University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments