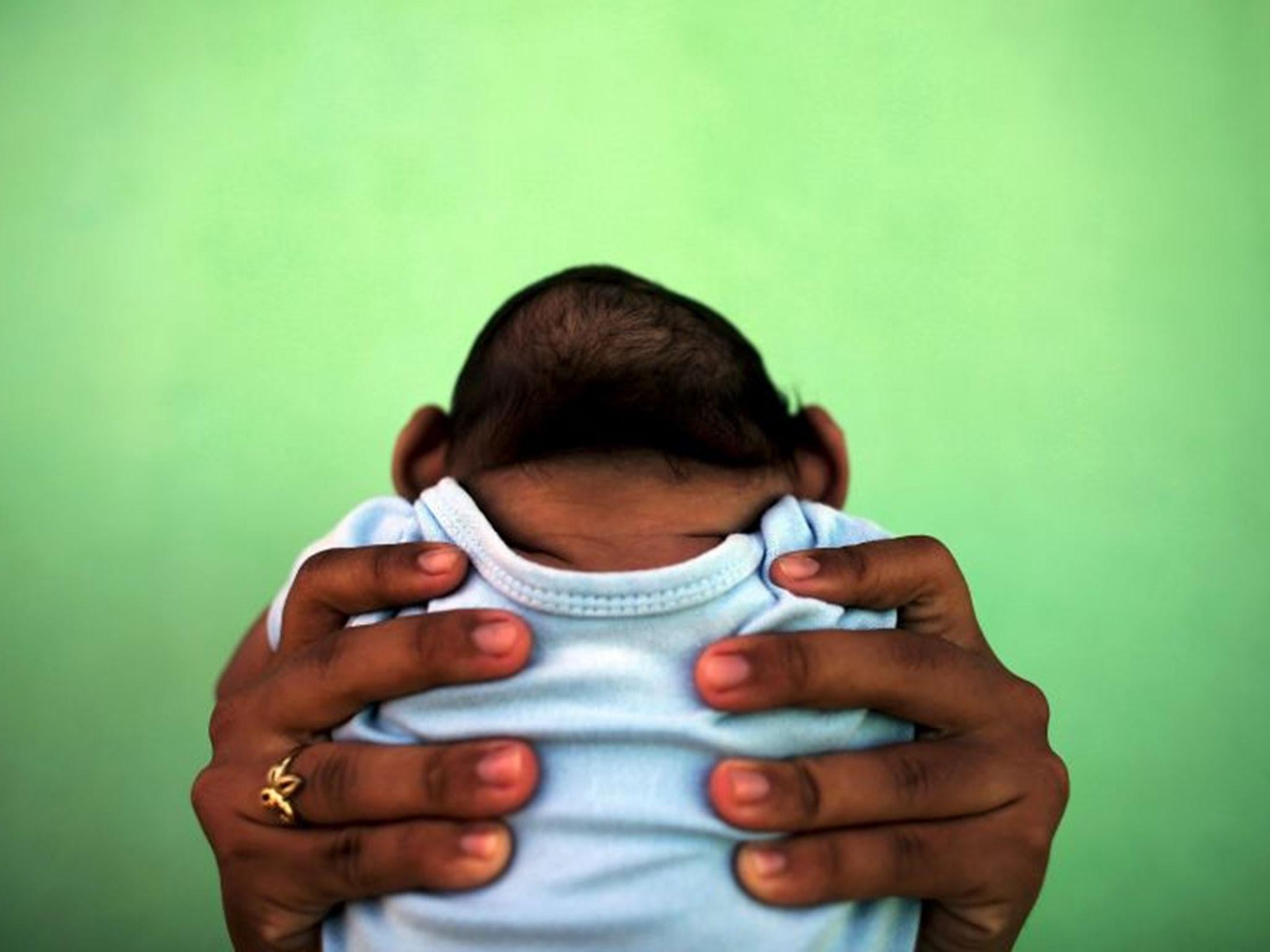

Zika breakthrough as scientists detail how virus attacks foetal brain

The World Health Organisation has said that 48 countries have reported local transmission of Zika

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In what has been hailed as a major breakthrough, scientists have announced they believe they understand how the Zika virus causes a rare birth defect in which babies are born without abnormally large heads and underdeveloped brains.

Working with lab-grown human stem cells, scientists found that the virus selectively infected cells forming the brain’s cortex, the thin outer layer of folded gray matter. Its attack made those cells more likely to die and less likely to divide normally and make new brain cells, the Washington Post reported.

Since the outbreak that has swept through the Americas first emerged, scientists in Brazil have raised concerns over a possible link between Zika and the birth abnormality, known as microcephaly.

Such was the weight of international concern, on February 1 the World Health Organisation declared the current outbreak a public health emergency.

The experts at Johns Hopkins, Florida State and Emory universities believe that while the breakthrough does not prove a definitive link between Zika and microcephaly, it does shed more light on how the virus attacks the body.

Professor of biological science Hengli Tang at Florida State University said: “We’re trying to fill the knowledge gap between infection and the neurological defects.

“This research is the very first step in that, but it’s answering a critical question. It enables us to focus the research. Now you can be studying the virus in the right cell type, screening your drugs on the right cell type and studying the biology of the right cell type.”

Researchers said their experiments suggest these highly-susceptible lab-grown cells could be used to screen for drugs that protect the cells or ease existing infections.

Dr Guo-li Ming, a professor of neurology, neuroscience, psychiatry and behavioral science at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, said: “Studies of foetuses and babies with the telltale small brains and heads of microcephaly in Zika-affected areas have found abnormalities in the cortex, and Zika has been found in the foetal tissue.”

“While this study doesn't definitely prove that Zika virus causes microcephaly, it’s very telling that the cells that form the cortex are potentially susceptible to the virus, and their growth could be disrupted by the virus.”

Though the Zika virus was discovered in 1947, there is very little known about how it works and its potential health implications, especially among pregnant women. Anecdotal evidence has suggested a link to microcephaly, a condition where a child is born with an abnormally small head as a result of incomplete brain development.

According to the World Health Organisation, 48 countries have reported local transmission of the Zika virus. The study was published on Friday in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

Separate research published in the journal The Lancet this week confirmed a link between Zika and Guillain-Barre Syndrome, a neurological disorder in which the immune system attacks the nervous system, causing temporary but sometimes severe paralysis.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments