World's first viable malaria vaccine could prevent millions of cases - and be available within months

Researchers said the vaccine was effective in more than a third of children when the first dose is delivered between the ages of five and 17 months

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The world’s first viable malaria vaccine could be available by as early as October, after final trial results confirmed its potential to prevent millions of cases of the deadly disease every year.

Researchers said the vaccine was effective in more than a third of children when the first dose is delivered between the ages of five and 17 months.

With an estimated 198 million cases of malaria a year, this level of protection could have a huge impact.

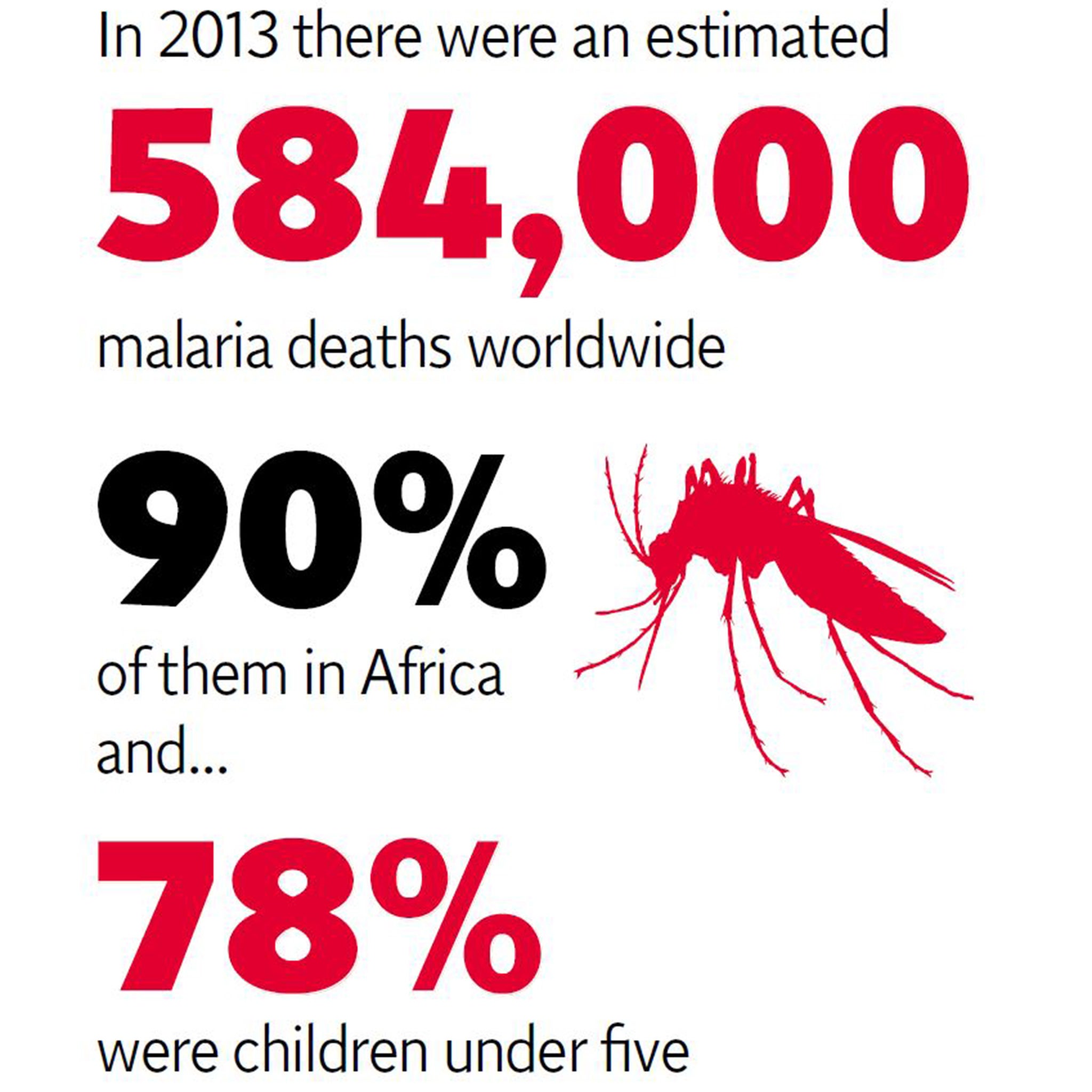

Malaria – one of the world’s biggest killers – has evaded vaccine manufacturers for many decades and the mosquito-borne disease still kills nearly 600,000 people a year – most of them children under 5, and the vast majority in sub-Saharan Africa.

Death rates have declined in recent years thanks to the wider availability of mosquito nets and malaria drugs, but an effective vaccine is considered the missing piece of the jigsaw in global efforts to control the disease.

The vaccine, RTS,S/AS01, developed by UK drugs giant GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, is the most advanced of several potential vaccines being developed around the world.

Trials began in 2009 and have led to the vaccine being tested in 15,459 children and infants in seven sub-Saharan African countries – Burkina Faso, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania.

The final results, published in The Lancet medical journal reveal that, while the efficacy of the vaccine wanes over time, for every 1,000 children vaccinated, an average 1,363 cases of malaria were prevented over four years – rising to 1,774 for those children who received a booster shot.

GSK has already sought licensing for the vaccine from the European Medicines Agency (EMA)on the basis of earlier results.

If the EMA approve it, the World Health Organisation has said it would consider the vaccine for use in immunisation programmes in Africa, with a recommendation possible by October.

The vaccine was tested in two age groups: infants who received their first shot aged six to 12 weeks, and children who had their first shot aged five to 17 months. All were given an initial series of three monthly doses, with some also given a booster shot 18 months later.

It was less effective in the infant age group. With a booster, it reduced the risk of malaria by 26 per cent over three years, but did not appear to offer protection against more severe cases.

However, among the older age group, the vaccine plus booster was 32 per cent effective against even severe cases.

Brian Greenwood, professor of clinical tropical medicine at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who took part in the study, said the vaccine had “clear benefit”.

“Given that there were an estimated 198 million malaria cases in 2013, this level of efficacy potentially translates into millions of cases of malaria in children being prevented,” he said.

Experts at the WHO’s department of immunisation said that early modelling suggested the vaccine could bring down child mortality, but urged that international funding for it should not come at the expense of spending on mosquito nets and artemisinin drug treatments.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments