World first as scientists use cold sore virus to attack cancer cells

Using genetically modified viruses to attack tumour cells could open a 'wave' of potential new treatments

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have the first proof that a “brand new” way of combating cancer, using genetically modified viruses to attack tumour cells, can benefit patients, paving the way for a “wave” of new potential treatments over the next decade.

Specialists at the NHS Royal Marsden Hospital and the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) confirmed that melanoma skin cancer patients treated with a modified herpes virus (the virus that causes cold sores) had improved survival – a world first.

In some patients, the improvements were striking. Although all had aggressive, inoperable malignant melanoma, those treated with the virus therapy – known as T-VEC – at an earlier stage survived on average 20 months longer than patients given an alternative.

In other patients results were more modest, but the study represents a landmark: it is the first, large, randomised trial of a so-called oncolytic virus to show success.

Cancer scientists predict it will be the first of many in the coming years – adding a new weapon to our arsenal of cancer treatments.

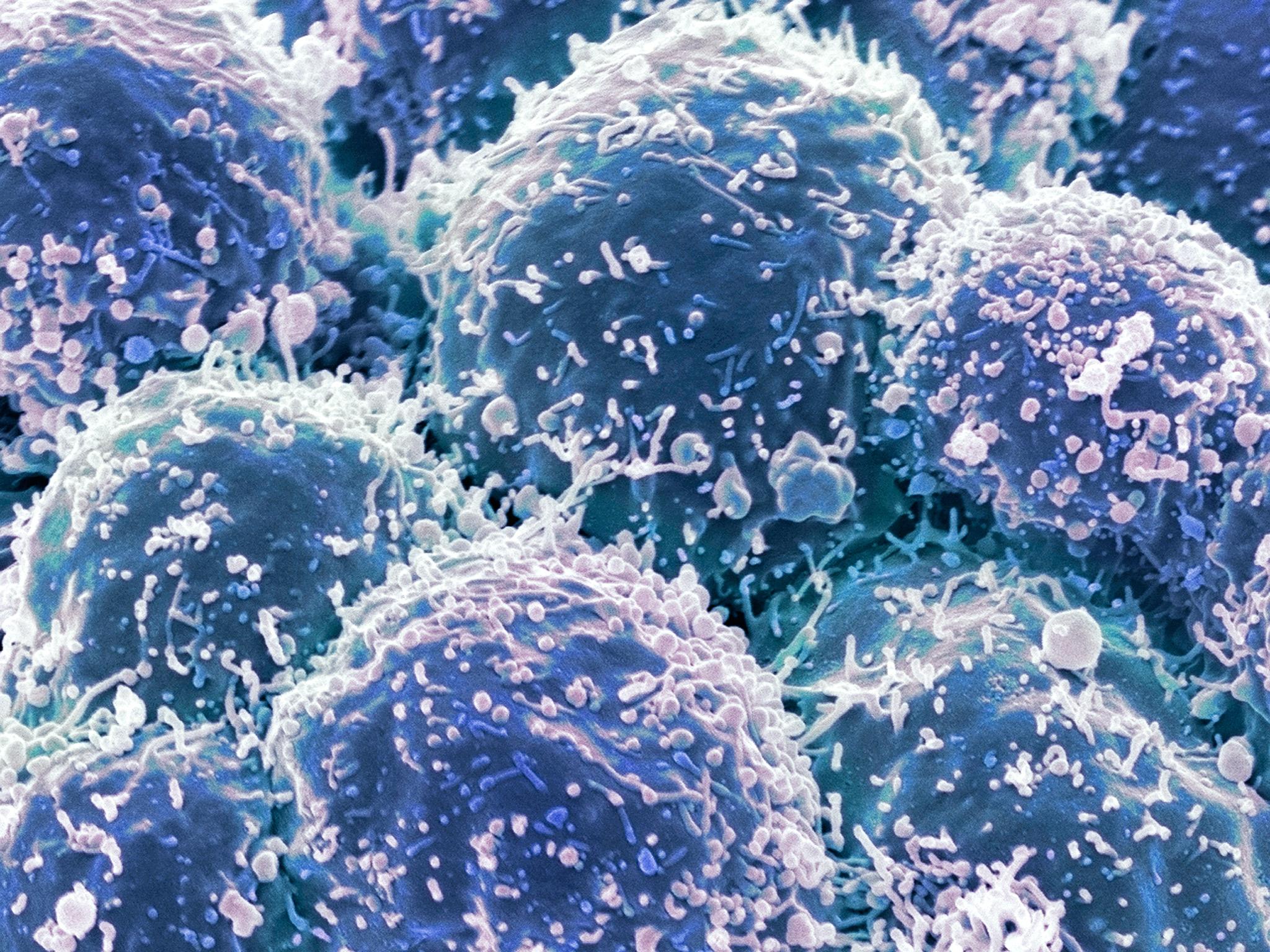

The method – known as viral immunotherapy – works by launching a “two-pronged attack” on cancer cells. The virus is genetically modified so that it can’t replicate in healthy cells – meaning it homes in on cancer cells.

It multiplies inside the cancer cells, bursting them from within. At the same time, other genetic modifications to the virus mean it stimulates the body’s own immune response to attack and destroy tumours.

Other forms of immunotherapy – the stimulation of the body’s own immune system to fight cancer – using antibodies rather viruses, have been developed into successful drugs. It is hoped that T-VEC could be used in combination with these.

Findings from trials of T-VEC, which is manufactured by the American pharmaceutical company Amgen, have already been submitted to drugs regulators in Europe and the USA.

Viral immunotherapies are also being investigated for use against advanced head and neck cancers, bladder cancers and liver cancers.

Kevin Harrington, UK trial leader and professor of biological cancer therapies at the ICR and an honorary consultant at the Royal Marsden, said he hoped the treatment could be available for routine use within a year in many countries, although it would need to pass the UK’s own regulatory approval before it could be prescribed here.

“I hope, having worked for two decades in this field, that it really is the start of something really exciting,” said Professor Harrington. “We hope this is the first of a wave of indications for these sorts of [cancer fighting] agents that we will see coming through in the next decade or so.”

Professor Paul Workman, chief executive of the ICR said: “We may normally think of viruses as the enemies of mankind, but it’s their very ability to specifically infect and kill human cells that can make them such promising cancer treatments.”

The study, which is published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, included 436 patients, all of whom had aggressive, inoperable malignant melanoma. More than 16 per cent of patients were responding to treatment after six months, compared to 2.1 per cent who were given a control treatment.

Some patients were still responding to treatment after three years.

Alan Melcher, professor of clinical oncology and biotherapy at the University of Leeds, and an expert in oncolytic viruses, said the field had accelerated quickly in recent years.

“They were first developed to go in and kill cancer cells but leave other cells unharmed. What’s become clear is that these viruses may do that but what is probably more important, is that they work by stimulating an immune response against cancer,” he said.

“The field has moved very quickly clinically. Immunotherapy looks promising and big pharmaceutical companies are now involved. Amgem have bought this virus and the reality is, when the big companies get involved things move a lot more quickly.”

Dr Hayley Frend, science information manager at Cancer Research UK, said the potential for viruses in future cancer treatments was “exciting”.

“Previous studies have shown T-VEC could benefit some people with advanced skin cancer but this is the first study to prove an increase in survival. The next step will be to understand why only some patients respond to T-VEC, in order to help better identify which patients might benefit from it,” she said.

Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer in the UK, and is becoming more widespread as a result of increased exposure to the sun in younger generations who have benefitted from easier access to sunnier climates on holiday. Survival chances are good if the cancer – indicated by the appearance of a new mole on the skin – is caught early.

However, if left alone, the tumour can become inoperable, and 2,000 people still die from melanoma in the UK every year.

Cancer Q&A

How can a virus fight cancer?

Viruses are good at infecting and killing human cells – that’s what makes some of them so dangerous. Genetic technology means that scientists can now manipulate viruses to behave in certain ways – in this case, to only infect and attack cancer cells – bursting them from the inside. These are called oncolytic viruses – from the Greek for ‘tumour’ and ‘loosening’.

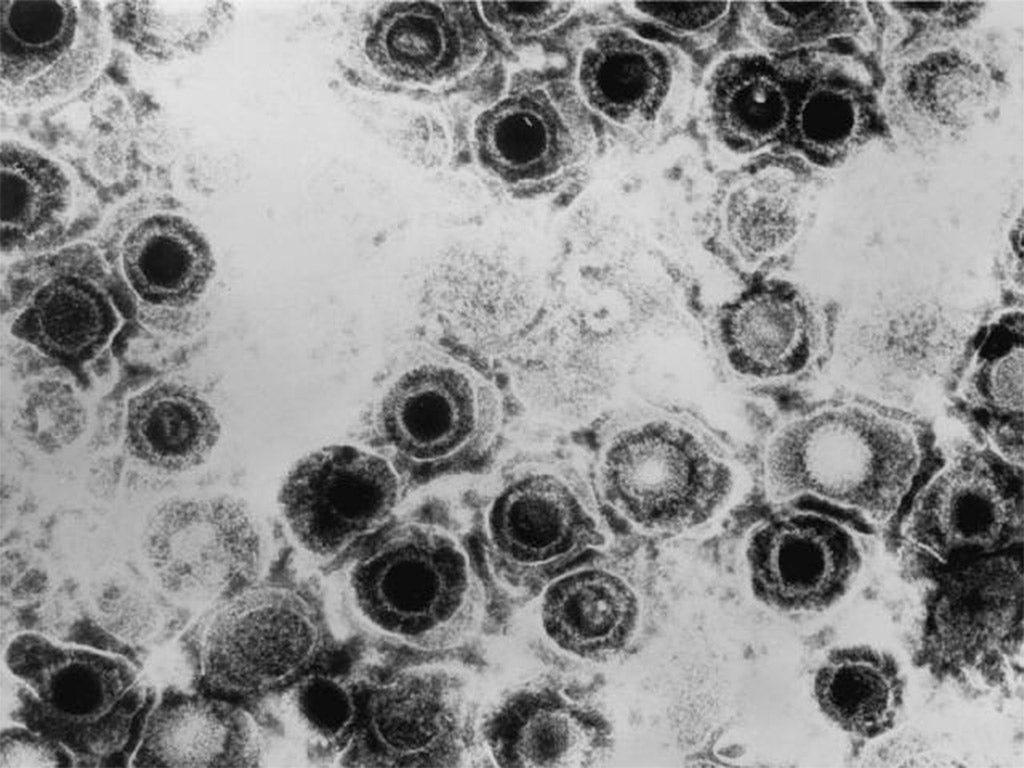

Why was a herpes virus used?

There is nothing intrinsic about the herpes virus that makes it a good cancer fighter. However, scientists have used the virus in labs for decades and understand a great deal about its structure – making it a good candidate for genetic modification.

Will oncolytic viruses work against all cancers?

We only have definitive findings from this ICR/Royal Marsden study, in melanoma skin cancer patients. However, the theory should apply to other tumour types, and scientists are confident that similar treatments for head and neck, bladder and liver cancers could emerge in the coming years.

How soon will the new treatment be available?

The therapy used here, known as T-VEC (short for Talimogene Laherparepvec) is already being looked at by regulators at the US Food and Drug Administration, and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Scientists hope that it could be rubber-stamped as a treatment for advanced melanoma within the next 12 months. If it gets EMA approval, it would then need to go through NICE approval, or be included on the Cancer Drugs Fund list, before it could be prescribed in the UK.

Are cancer-fighting viruses our best chance of beating the disease?

The most likely scenario is that these treatments will take their place alongside the growing range of drugs and therapies being developed. This is a time of very rapid progress in cancer treatment, with our greater understanding of the genetics of cancer fuelling a raft of wave of new discoveries. However, we also know that cancers vary hugely from one to the other, so the idea of one ‘silver bullet’ cure for cancer is no longer considered a realistic prospect.

How can I avoid developing melanoma?

It is not always preventable but you can lower your risk by limiting exposure to UV light – avoid sunbeds, wear sunscreen, and check moles and freckles for any changes.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments