The NHS timebomb: What is wrong with the NHS? The diagnosis

Why are so many people so worried about the health service’s finances – and future? Charlie Cooper explains

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What does an NHS funding crisis mean?

Put simply, the amount of work hospitals, GP surgeries and community carers have to do will cost more than the £113bn budget the Government has given it to spend.

On current trends, the NHS in England will run out money this year or next. With demand increasing all the time, by 2021 the NHS in England will be £30bn short of what it needs to provide an effective service, free at the point of use.

“It’s not possible to have a £30bn gap,” said one senior NHS source. “It has to be paid from somewhere – you would have to have emergency Treasury bailouts, which the Treasury would be furious about.”

Has the NHS gone into the red before?

Yes, most recently in 2005-06. There have also been times when its budget was a smaller proportion of GDP than it is today. But there is a growing consensus among health economists that the outlook in 2014 is bleaker than previous times of NHS funding pressures.

What has caused the current crisis?

All NHS funding crises boil down to the health service having too much work to do with not enough money to do it – a consequence of rising patient demand. But two things are different about the situation today.

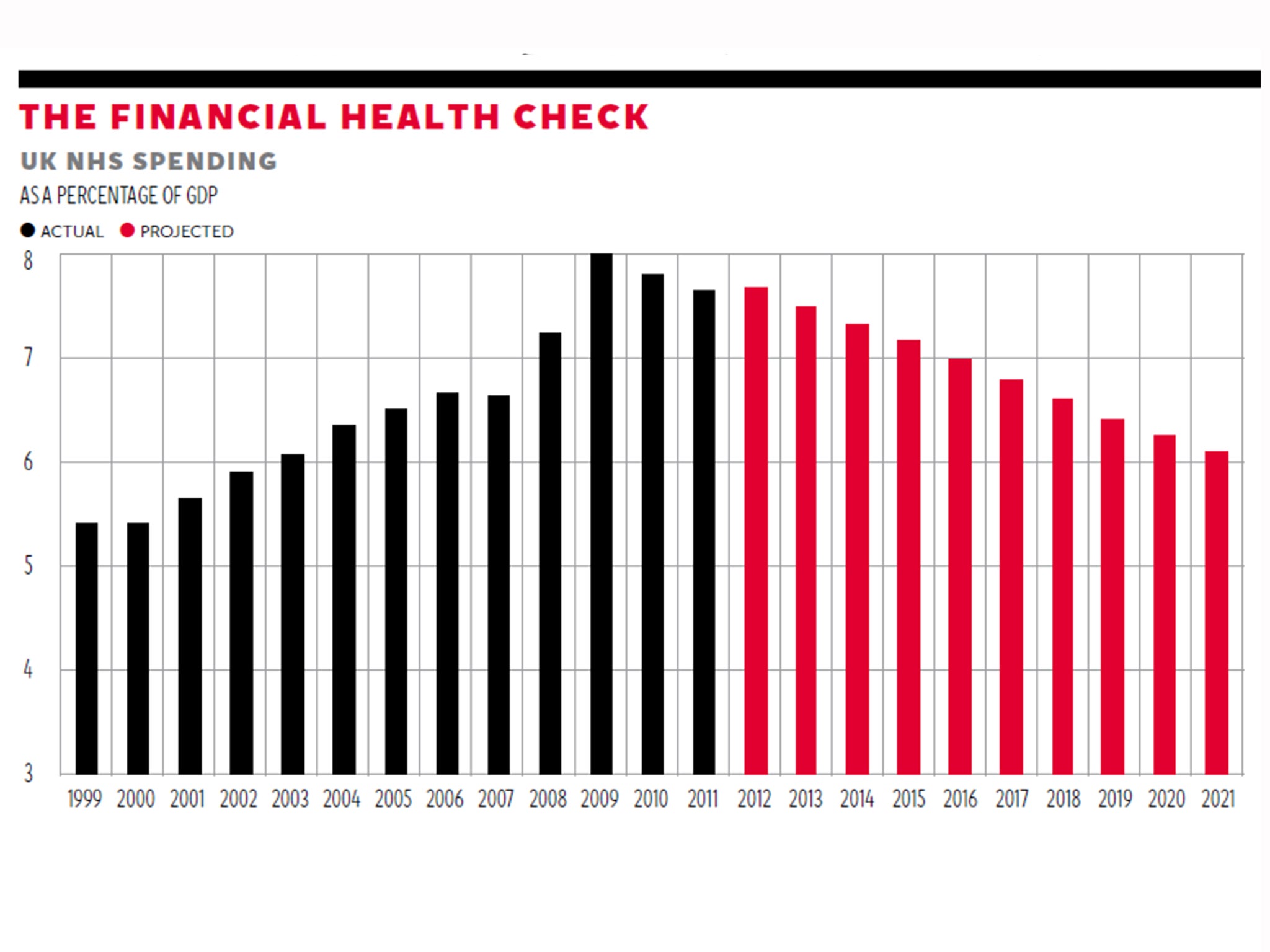

One is the recent historical context. The NHS is entering this crisis at the end of the longest spending squeeze in its history. In 2010, as part of the Coalition’s deficit reduction strategy, it set out a spending plan, which amounted to annual increases of just 0.7 per cent above inflation, scheduled to last until 2015-16.

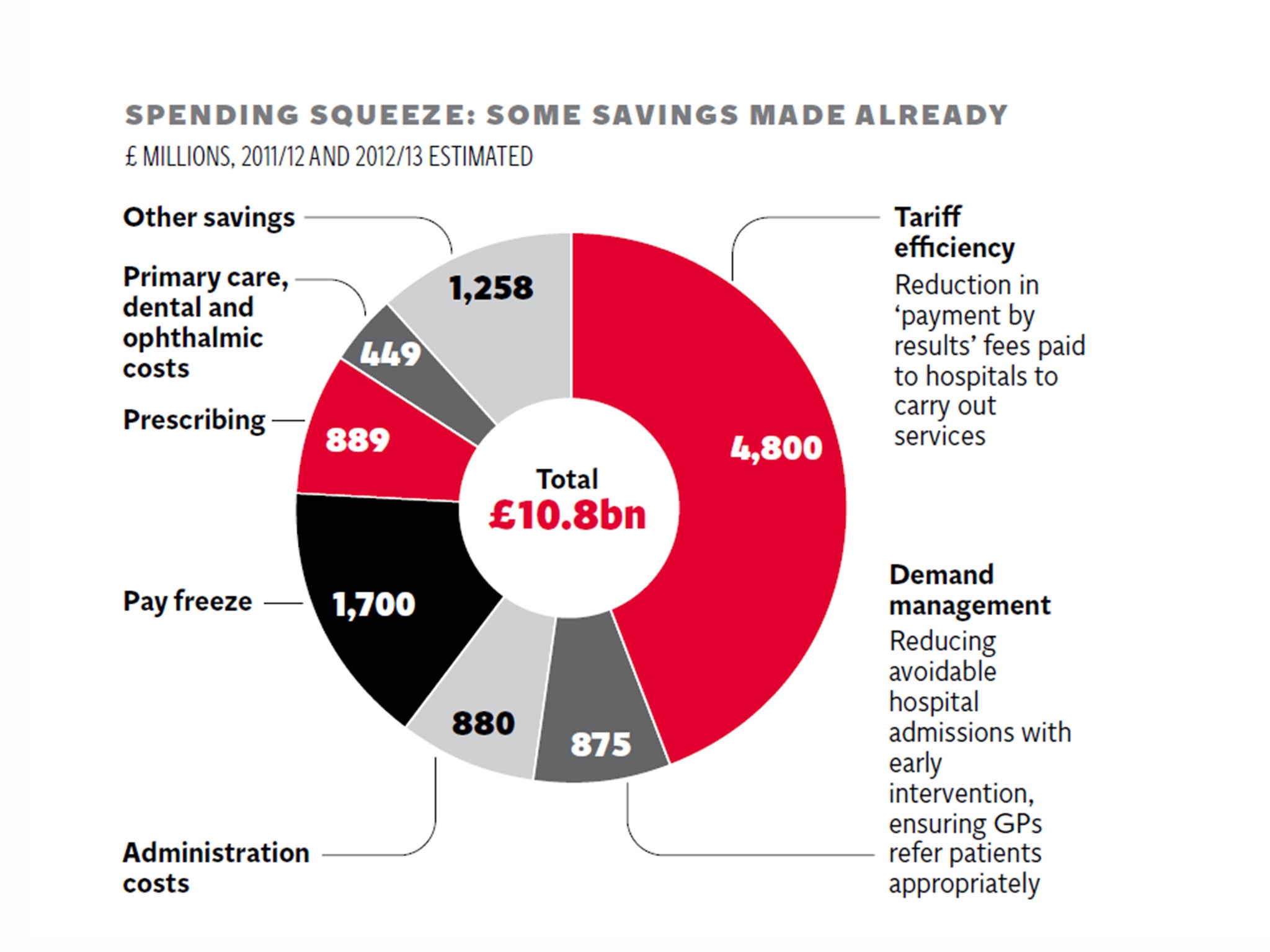

To put this into context, the average annual spending increase for the NHS over its entire history has been 4 per cent. The NHS has had to tighten its belt to cope. There has been a staff pay freeze, management costs have been cut and fees that hospitals are paid to carry out treatments have been reduced. The NHS saved nearly £11bn between 2011 and 2013 through these and other measures. In terms of cutting costs, the “low hanging fruit” has been picked. The only things left to cut are things patients care about: staff and services.

However, the other new thing about today’s funding crisis is that the public, the inspectors and the Government now hold NHS care to a much higher standard. In the past, when money became tight, the NHS has cut costs by doing less: letting waiting times slip, cutting staffing levels, and generally letting the quality of the service drop.

But pressure from a public and media more conscious of the NHS’ fallibility since the care failings at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust means this is, rightly, no longer considered acceptable. Facing a strict new inspection regime, hospitals set out to improve their standard of care in the wake of the Francis report into Mid Staffs, with an expensive recruitment drive at a time of financial austerity. More than 18,000 additional full-time equivalent staff were taken on in 2013-14 – a 1.6 per cent increase.

The financial pressure that this entailed has been justified by hospital managers who now commonly say they would rather be criticised for running out of money, then for a care scandal on their watch.

If not the quality of care, something else will have to give: senior health officials admit in private that if no money comes from Government, the NHS will have to look at whether it can afford to provide all the services it currently offers, for free. That of course, runs counter to the basic principle of the NHS. In this context, the NHS is not just facing a funding crisis, but an existential one too.

Adding to pressure on hospitals, next year nearly £2bn will be sliced off the NHS’ budget and reallocated to social care. The Better Care Fund, which will total £3.8bn, is intended to be a first step towards changing how our health and social care system work together to keep the elderly and the chronically ill out of hospital – a long-term goal shared by politicians and NHS managers.

But the fund has created a cliff edge in 2015-16, which some analysts say could leave the NHS as a whole £1bn or £2bn in the red.

NHS England hopes for a 15 per cent drop in emergency admissions to hospital by 2015-16. Hospital bosses doubt this is possible and pressure is growing for a “transformation fund” to see hospitals through this transition era.

How has NHS demand changed in recent years?

Underlying the financial problems is ever-growing patient demand.

Population growth and advances in medical knowledge which have led to us living longer, have also, paradoxically increased our need for healthcare.

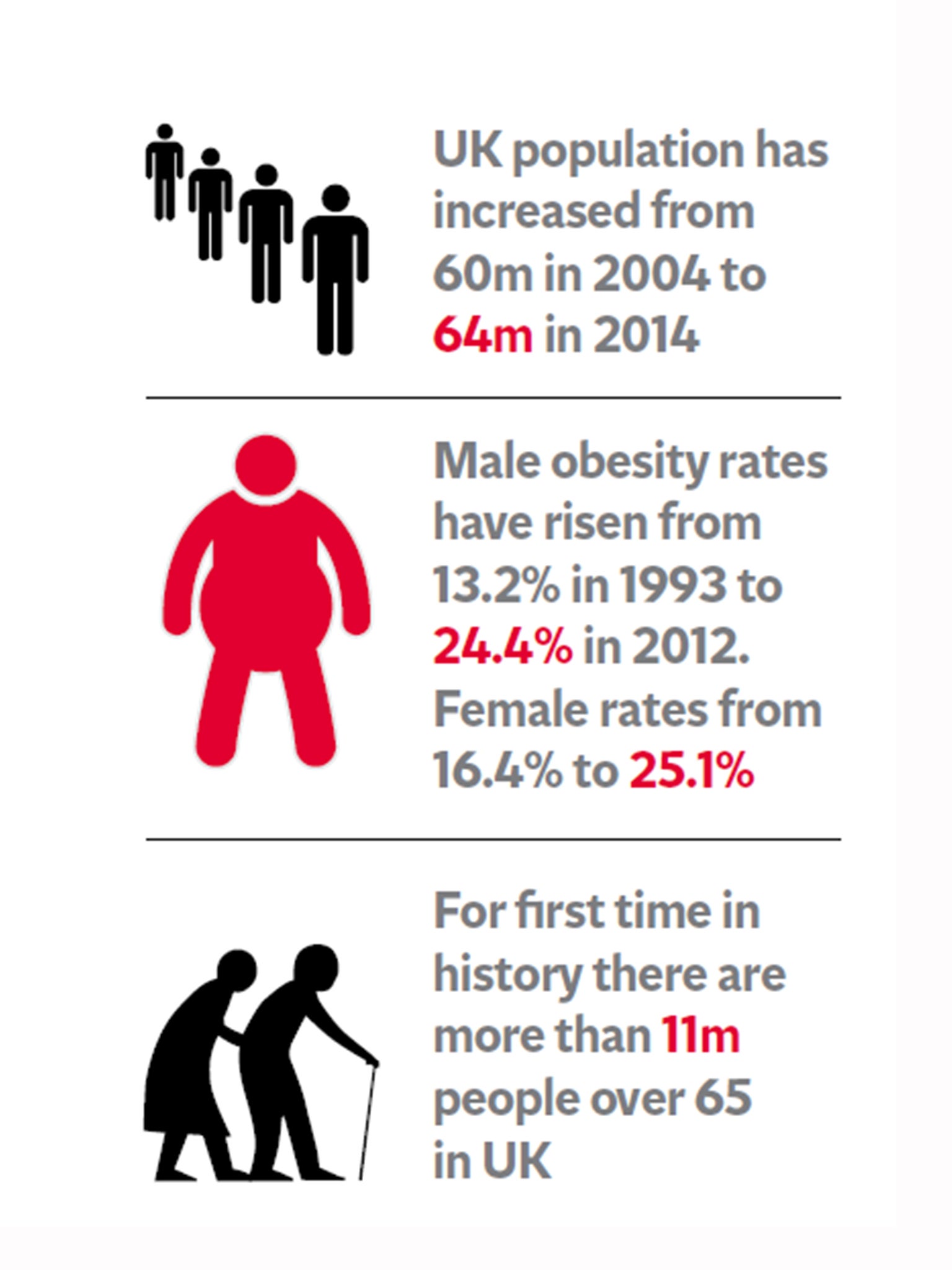

In 10 years, the UK population has gone up from just under 60 million to 64 million. The population is also older. In 2010, around 640,000 people turned 65. In 2012, it was 800,000. While we are, on the whole, living healthier for longer, this brings an additional burden from diseases that predominately affect the elderly.

Although smoking rates have fallen over time, obesity rates have risen dramatically, up from 13 per cent in men and 16 per cent in women in 1993, to 24 per cent and 26 per cent in 2012. Diabetes, which is linked to obesity, now costs the NHS billions of pounds.

The health service has had to keep up with all these changes. The number of hospital admissions has risen from 11.4 million a decade ago to 15.1 million in 2012-13 and the number of A&E attendances from 14 million to 21.7 million.

It has 38,000 more doctors than a decade ago, and 23,500 more nurses, out of a total current staff of 1.7 million.

Will funding problems impact on patient care?

In the past year cracks have begun to show.

Major A&E units have not met their target to admit or discharge 95 per cent of patients in under four hours for well over for a year.

In the first half of 2014, nearly 10,000 patients in England had to wait more than two months for specialist treatment after being told by their GP that they had a suspected cancer – a rise of 27 per cent on the same period last year.

With hospitals already struggling just to pay the bills and get patients through the door, and with winter, the busiest time for hospitals, just around the corner, the NHS funding crisis could become an NHS care crisis sooner than the Government would care to believe.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments