Study which shows how sneezes travel 'could help stop spread of disease'

Scientits 'tickled' the noses of 100 people to map sneezes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have plotted how sneezes spread in the air, in research that they hope will help prevent diseases from spreading.

Researchers at the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US used high-speed cameras to film more than 100 people sneezing.

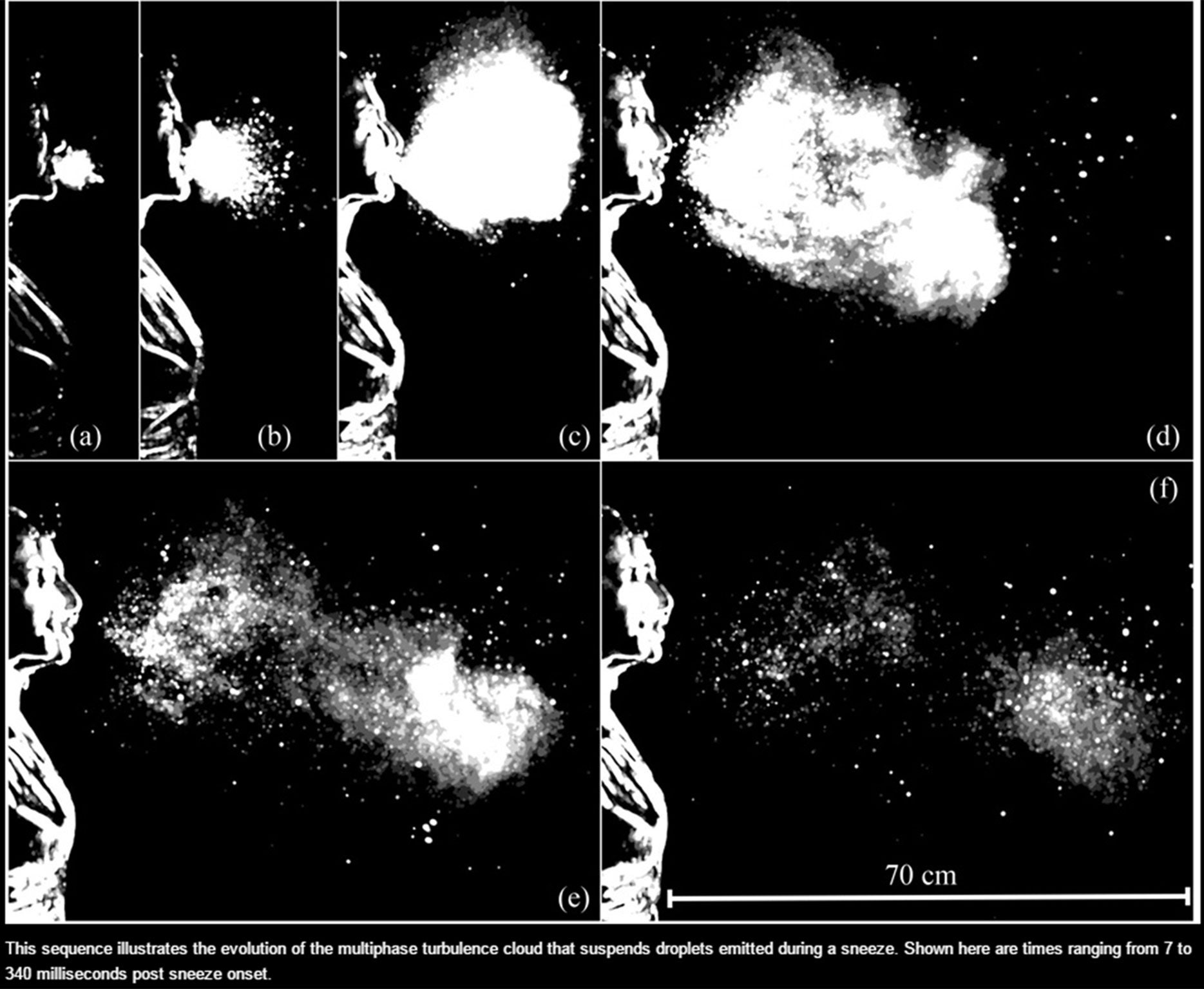

They found that the process is similar to flinging paint from a brush, as sneezing causes a sheet of fluid to be expelled into the air. This then balloons and breaks apart, before finally dispersing as droplets.

The more elastic the saliva, the longer it would travel before separating into droplets.

The team behind the research said their results go against the common belief that sneezes create a simple and uniform spray of liquid.

The research published in the journal ‘Experimental Fluids’ builds on previous research reported in 2014, which showed how coughs and sneezes produce a mound of gas which carries infectious droplets 200 times farther than if they were disconnected drops.

In the latest experiment, researchers “tickled” the subjects' noses, and recorded them sneezing against a black backdrop.

Lydia Bourouiba, the Esther and Harold E. Edgerton Assistant Professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and head of the Fluid Dynamics of Disease Transmission Laboratory at MIT said that understanding how fluid from sneezing behaves can help to map the spread of infection and identify individuals known as “super spreaders”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments