Simple blood test could save hundreds from ovarian cancer

A £20 blood test given to women with suspected ovarian cancer could save hundreds of lives a year, experts said yesterday.

Almost 7,000 women develop ovarian cancer annually, but unlike breast cancer, where more than two thirds survive five years, nearly two thirds of women with ovarian cancer die within five years.

Late diagnosis is the main cause of the high death rate – ovarian cancer is known as the "silent killer" because by the time it is detected the disease is often far advanced.

In the first guidelines for GPs on the disease issued today, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (Nice) dismisses the "misconception" that its symptoms are vague and says doctors should offer a blood test to women at risk.

Swift diagnosis aided by the blood test could help save up to 500 women's lives a year if Britain matched the average survival rates of other European countries, figures show.

Ovarian cancer is the fourth biggest cancer killer of women, after lung, bowel and breast cancer. But if diagnosed early, nine in 10 sufferers can be treated successfully.

Fergus Macbeth, of Nice, said: "The outcomes for ovarian cancer are not as good as for other cancers in women. We do not seem to do as well as other European countries. Its symptoms are considered vague, and so can be confused with other conditions. This misconception can lead to many women... being diagnosed once the cancer is at an advanced stage. The stage at diagnosis is the most important factor in predicting survival."

The guidelines list four warning signs of ovarian cancer: bloating, feeling full quickly, pelvic pain, and urgent need to urinate, which, if persistent more than 12 times a month, should lead doctors to offer a blood test.

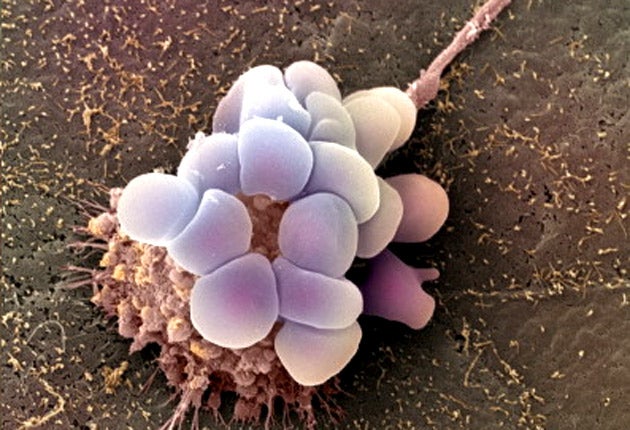

The test measures the level of a protein called CA125 in the blood, and is 50 per cent accurate in diagnosing early cases and 80 per cent accurate for advanced cases.

Specialists admitted that the test could give women false reassurance if the result was negative and they later turned out to have the cancer. GPs are urged to monitor the symptoms, and if they persist, refer the woman for an ultrasound scan which provides a more definitive diagnosis of the potential problem.

Sean Duffy, medical director of the Yorkshire Cancer Network who led development of the guideline, said: "There isn't a perfect test out there. We are trying to improve a system that is far from good. If the test is negative and the symptoms persist, they will need further investigation which will normally involve an ultrasound test. If the blood test and ultrasound are negative, they are unlikely to have ovarian cancer."

The extra costs of testing women in general practice are likely to be offset by savings from inappropriate tests currently carried out, he said.

Frances Reid, a member of the group that developed the guidelines and director for public affairs at the charity Target Ovarian Cancer, said: "Poor early diagnosis in Britain is strongly linked to poor survival rates. Up to 500 women's lives a year could be saved if only we matched the average survival rates in other European countries."

Case study: 'I had no idea about my tumour'

Linda Facey, 53

The former care home inspector was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2001. After her stomach swelled, her GP in Gosport, Hampshire, diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome. "He was a lovely man, not dismissive, and kept me coming back four times in seven weeks. But between us we did not pick up the symptoms of ovarian cancer," she said.

By the time she was diagnosed, the cancer was stage three: advanced. She had four courses of chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy until she was declared free of symptoms in 2007.

"My experience highlights the importance of paying attention to the symptoms. We shouldn't put concerns about our bodies on the back burner," she said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks