Revealed: the genes that make some smokers more prone to cancer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have identified for the first time genetic variations that increase the risk of lung cancer in people who smoke.

The finding shows that some people have an inherited susceptibility to the cancer, which makes them more vulnerable to the damaging effects of tobacco. The genetic variations are widespread, affecting up to half the population, and increase the risk of lung cancer in smokers by up to 80 per cent.

But scientists stressed yesterday that the discovery did not amount to a "licence to smoke" for people free of the genetic variants. The risk of lung cancer remains high in all smokers, regardless of their genetic make-up. The finding could allow stop-smoking services to be targeted at those at highest risk, who have a one-in-four chance of developing lung cancer. Those without the gene variants who smoke have about a one-in-seven chance.

Three separate research groups – in Britain, France and Iceland – which used newly developed methods to scan the human genome independently reached the same conclusion, strengthening confidence in their results. The findings are published in Nature and Nature Genetics.

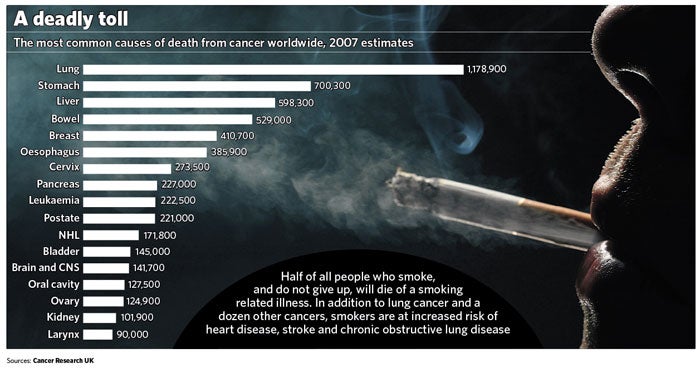

More than one million cases of lung cancer are diagnosed each year worldwide and it is the most common cause of cancer-related deaths. In Britain, there are more than 38,000 new cases annually, and 33,000 deaths. Nine out of 10 cases in Britain are caused by smoking. Smokers are 26 times more likely to develop the disease than non-smokers.

By comparing the frequency of more than 300,000 gene variants in thousands of lung cancer patients, the three research groups narrowed the search down to two genetic variants on chromosome 15. Smokers with one copy of the two variants – present in half the population – have a 30 per cent increased risk of lung cancer, and those with two copies – one in 10 of the population – have an 80 per cent increased risk, compared with smokers without the variants.

But the underlying risk of developing lung cancer is already very high in smokers. In non-smokers, in whom the risk of lung cancer is less than 1 per cent, the presence or absence of the gene variants appears to make no difference (though one study suggested they might have an impact), implying that the genes are switched on by nicotine or other constituents of tobacco smoke.

Paul Brennan, of the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyons, France, who led one of the studies, said: "What is important for the individual is the absolute risk of getting lung cancer. If you smoke all your life it is about 15 per cent, and if you have no copies of the gene variants it will be a bit less. But if you have two copies it will be closer to 25 per cent. Obviously, even in those who have no copies there is still a very high risk of lung cancer in those who smoke."

The use of genome scanning techniques has already yielded new insights into the genetics of breast and bowel cancer, but this is the first time it has been used in lung cancer. Dr Brennan said the main benefit of the research lay in increasing understanding of the disease, not in identifying vulnerable smokers. "This gives us information about how cancer develops, which provides a target for pharmaceutical companies to develop new treatments," he added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments