Profits before patients: The export of prescription medicines

Watchdog ready to warn manufacturers and wholesalers that they face possible legal action

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Profiteering pharmacists, hospitals and wholesalers are putting British patients' lives at risk by selling prescription drugs, intended for the UK, to customers in Europe.

Nearly 50 drugs needed by patients, with conditions ranging from breast cancer and Parkinson's disease to depression and epilepsy, are in short supply because traders are selling the drugs for higher prices overseas in a trade worth at least £360m a year.

The medicines and healthcare regulator, the MHRA, is set to write to all drug manufacturers and wholesale licence holders warning them they could face legal action if caught exporting drugs needed by British patients. The move follows recent guidance issued by the Department of Health, regulators and professional bodies to "remind" all potential traders of their legal obligations to prioritise UK patients before profit.

Last week, MPs were told that between 300 and 500 worried patients are calling drug companies because they cannot get their medication.

Pharmacists and patient groups warn "it is only a matter of time before a patient suffers serious harm" unless the whole industry accepts responsibility and starts putting patients first. Industry insiders suggest some patients have been missing doses of essential medicines for more than a year.

A detailed "shopping list" of drugs wanted for export in November currently circulating among pharmacies, dispensing doctors, wholesalers and hospitals and seen by the IoS includes several drugs in short supply, including Azilect for Parkinson's and Femara for breast cancer, which no one should be buying or selling.

Norman Lamb MP, the Lib Dem health spokesman, said: "There is no doubt there are unethical and criminal activities going on, yet the reaction so far has been wholly inadequate and the problem has been allowed to get worse. While a total crisis may have been averted so far, in that no one has died as far as we know, this is causing immense disruption and distress for many patients already struggling to cope with illness."

Research by the consultants IMS revealed that 11 per cent of UK pharmacies and a small proportion of dispensing doctors are exploiting the European market and effectively diverting £30m worth of medicines meant for Britain to patients overseas every month. Wholesalers are also believed to be playing a "very significant role", says the pharmaceutical trade association, ABPI. An increase in production has led to more exports while the shortages have continued.

Many pharmacists find themselves caught between wholesalers and manufacturers, who blame each other. There were 77,000 emergency deliveries made to pharmacies by just three drug companies in the first five months of this year – a 12-fold increase on the same period last year, says the ABPI.

James Wood, a pharmacist in Sheffield, spent two hours on the phone last Wednesday trying to secure emergency supplies for four patients. This is now part of his daily routine and means he, like thousands of other pharmacists, has less time to spend with patients.

Drug companies sell the same drug at different prices in every country. In the past, Britain was one of Europe's biggest importers of "cheap drugs" from Spain and Greece. But since the pound fell against the euro and UK drug prices dropped, the tables have turned and there is now a massive demand for British medicines overseas.

The MHRA has issued 180 new wholesale licences so far this year – a 59 per cent rise on the total number issued in 2008. Authorised traders do not need to seek permission to import or export within the EU as free-market principles also apply to medicines. But they do have a legal duty to ensure UK patient needs are met.

Yet the expanding list of scarce drugs suggests these rules are being flouted. Mr Lamb said: "The DoH must initiate an urgent investigation into those companies and individuals involved and put a stop to this despicable, unethical and illegal trade."

David Pruce, from Britain's Royal Pharmaceutical Society, said: "Everyone else as the perpetrator when the reality is that everyone on the supply chain has a proportion of the blame. We want an independent inquiry to bring all sides together and resolve this problem. We don't care who's to blame. Let's just get it sorted because it won't be long before a patient is seriously hurt. There are 46 drugs on the list; this is hugely serious and my impression is that it's getting worse."

A DoH spokesperson said: "We have made clear the legal and ethical duties on wholesalers and manufacturers to supply medicines to patients. Breaching the legal duties could lead to investigation and action by the regulator, the MHRA."

Victim 1: 'It is criminal that market forces come ahead of people'

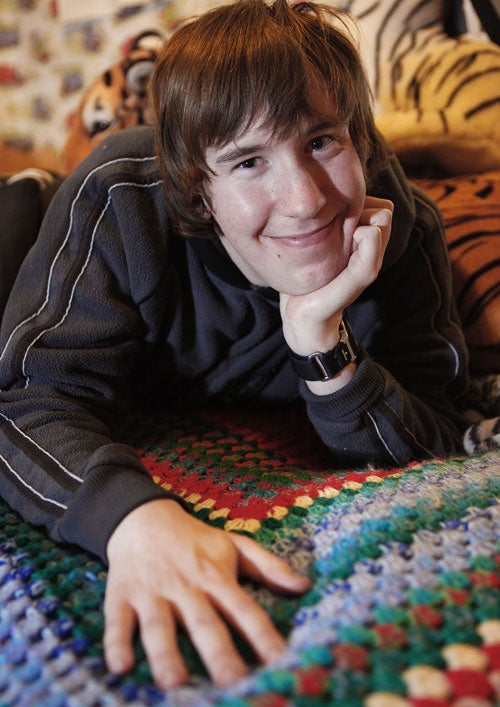

Kip Chillingworth, 22, from north London, was diagnosed with epilepsy when he was five years old. In April, neurologists recommended he start taking the anti-epileptic drug – Keppra – because he was still having seizures on his existing medication. His mother, Dr Saddi Chillingworth, struggles to get hold of it.

"Kip has been the drug Lamotrigine for years, but it was not controlling his seizures very well. A consultant recommended Keppra. We were to start with a low dose and increase it slowly. So in mid-April I got the prescription from the GP and went to my local pharmacy, but I couldn't get the drug. This went on for 10 days, and at that point I phoned Epilepsy Action and was told I wasn't the first person to complain. The distributors of drugs can sell to Europe at a better price, so there's a shortage here. I was crushed and angry.

The pharmacist demanded that the drug be made available and it did eventually come through. But by then I was reluctant to start my son on it, in case the supply was erratic. You never withdraw an anti-epileptic drug suddenly because the consequences can be dire, even fatal. In the end, Kip had to wait two weeks to get the drug.

I make sure I have a prescription at least two weeks before I run out, but this can make life very difficult as you can't always plan in advance. I've been told to 'shop around', but when you are caring for someone you can't just get up and go. Britain has enough drugs, so it is criminal that market forces are coming ahead of people's health and lives. People with epilepsy must be so stressed, and that is a trigger for seizures."

Owen Van Spall

Victim 2: 'Pharmacy had to use their emergency supply'

Marion Wilkes, from Oxfordshire, was diagnosed with breast cancer in June 2007. She is prescribed Arimidex – a hormonal therapy – to treat the tumour and minimise its risk of returning. She has been unable to get a full prescription since July.

"The pharmacy has had to use their emergency supply to fill my prescription since July. Until then, there wasn't a problem. The pharmacist told me that they can only supply me at the beginning of each month because they are given a quota, yet my medication is prescribed in two monthly amounts. This has been going on since the summer and every month now seems like they are doing a juggling act. From what I've understood, the Boots pharmacy put in their orders but they don't know what will be delivered. But they can't know how many people are going to come in and ask for the drug, so then what happens?

I'm really concerned about it, even though I'm fairly assertive and articulate and work as a volunteer for Macmillan. What worries me is that people, if refused the full supply of the drugs, might just walk away and accept this. My conversations with Macmillan and other patients have led me to believe that this is quite widespread. At the moment I have a few weeks' supply. Usually I would renew about a week before I'm due to run out, but now I know I'll have to go much sooner. I'm worried that one of these days I might go in and not get my supply."

Owen Van Spall

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments