Pratchett backs rejection of dementia 'death sentence'

Author welcomes launch of study saying sufferers can still lead fulfilling lives

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.People with dementia can still lead active and fulfilling lives despite society's view that it is a "death sentence", according to a report published today.

Most people believe the ability to lead a full life stops when Alzheimer's is diagnosed but a new study shows the reverse is true. A poll of more than 2,000 members of the public found only one in seven (13 per cent) believe somebody with dementia can have a good quality of life at all stages of their condition.

More than half (54 per cent) think a diagnosis of dementia would have a bigger impact on their quality of life in later life than with cancer (19 per cent) or a physical disability (16 per cent).

Over half of people (52 per cent) said dementia had a stigma attached to it.

The study, from the Alzheimer's Society, also interviewed people living with dementia, asking what was important to them for a good quality of life. The study found that the most important thing was maintaining relationships with family or friends and having someone to talk to. A good environment, such as being at home, was the next most important thing followed by maintaining physical health.

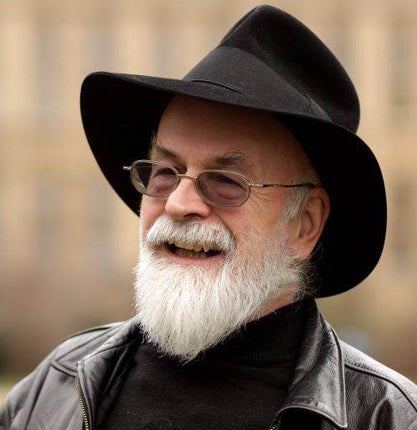

Author Sir Terry Pratchett, who has posterior cortical atrophy, a rare form of dementia, welcomed the launch of the study, My Name is Not Dementia.

He said: "Dementia is undoubtedly a cruel and debilitating condition. However, a diagnosis does not strip a person of their identity. That person still has a voice and they deserve to be heard. Dementia requires not just care but also understanding. We have to learn to be good at it."

However, people with dementia who were interviewed for the report said they had lost friends as a result of their diagnosis. One said: "Friends... well you think they are your friend. You walk down the road and they will walk over the other side and you walk in a pub and they walk down the other end of the bar."

Former warehouse manager Bill Wilson, 60, from Coventry has been battling against stereotypes ever since he was diagnosed with early onset dementia when he was 56.

A former Royal Marine, who spent many years coaching young people in athletics, he said: "People don't talk about dementia enough. But when they do the word "demented" often comes out and that is a terrible word.

"I am as fit as I was when I was in the Royal Marines. I want to carry on living as I have lived for the last 40 years. I want to go out and do anything and everything I have done before. Obviously, certain thing will have to be done with care but with my family to look after me I see absolutely no reason why I shouldn't live an active life."

There are 750,000 people living with dementia in the UK, according to the latest figures. This includes more than 16,000 people aged under 65. One in 14 people over 65 have a form of dementia and one in six people over 80. Dementia currently costs the UK £20bn each year. By 2021, it is estimated there will be 940,000 people with dementia in the UK, rising to 1.7million by 2050.

Ruth Sutherland, acting chief executive of the Alzheimer's Society, said: "All too often dementia is seen as an insurmountable barrier and a diagnosis is seen as a death sentence. This doesn't have to be the case.

"We need to learn to see the person not just the dementia."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments