Potential revolution in cancer treatment voted breakthrough of the year by scientists

New treatment uses body’s own immune defences to seek out and destroy tumour cells wherever they appear

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A potential revolution in cancer treatment that involves harnessing the body’s own immune defences to eliminate tumours has been voted breakthrough of the year by the Washington-based journal Science.

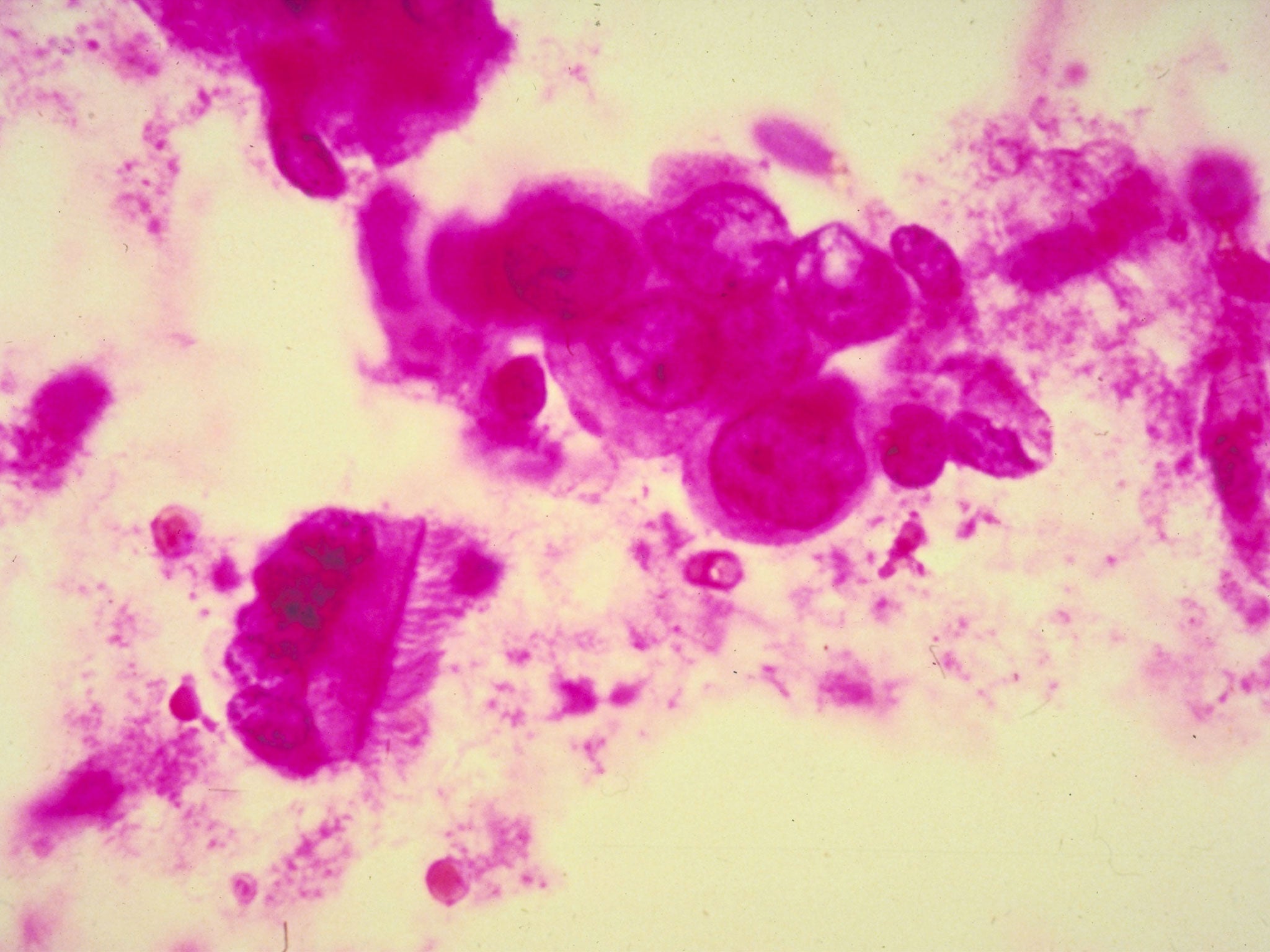

The experts behind the vote said there was a sense of a “paradigm shift” in cancer treatment as a result of the latest research into using the body’s own immune defences – antibodies and T-cells – to seek out and destroy tumour cells wherever they appear.

Cancer immunotherapy marks a turning point in cancer because it is so different to conventional forms of tumour therapy and this year saw encouraging results from some of first clinical trials of drug treatments based on the revolutionary approach, said Science.

“Immunotherapy marks an entirely different way of treating cancer by targeting the immune system, not the tumour itself. Oncologists, a grounded-in-reality bunch, say a corner has been turned and we won’t be going back,” it said.

Scientists are exploring several approaches to cancer immunotherapy. One involves the manufacture of monoclonal antibodies, such as a drug called ipilimubab which binds to T-cells causing them to proliferate and destroy cancers.

Bristol Myers Squibb, which manufactures ipilimubab, reported this year that out of 1,880 patients with advanced melanoma cancer, 22 per cent were still alive after 3 years – a significant improvement on previous treatments.

Other companies are working on ways of genetically modifying a patient’s own T-cells so that they target tumour cells. Early tests have shown it to be effective against leukaemia.

Meanwhile, in Britain a company called Immunocore based near Oxford has developed a drug molecule that acts like a double-sided glue to stick T-cells specifically to certain types of cancer cells – leading to their eventual destruction.

“This year there was no mistaking the immense promise of cancer immunotherapy,” said Tim Appenzeller, the chief news editor of Science who was involved in the selection of breakthrough of the year.

“So far this strategy of harnessing the immune system to attack tumours works only for some cancers and a few patients, so it’s important not to overstate the immediate benefits. But many cancer specialists are convinced that they are seeing the birth of an important new paradigm for cancer treatment,” Mr Appenzeller said.

One of the runners-up to the breakthrough of the year was a gene-editing technique called CRISPR which allows scientists to change any part of the genome of animals and plants, down to the smallest alterations in the DNA sequence.

“CRISPR is absolutely huge. It’s incredibly powerful and it has many applications, from agriculture to potential gene therapy in humans,” Craig Mello of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, who shared the 2006 Nobel prize in medicine, told The Independent in November.

“It’s a tremendous breakthrough with huge implications for molecular biology and molecular genetics. It’s a real game changer,” Dr Mello said.

Coincidentally, the rival journal Nature has voted a leading CRISPR researcher as one of the ten people of 2012 who “mattered most”. Feng Zhang of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge was one of the first to show that CRISP works in human cells, which could lead to new treatments for genetic disorders.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments