People infected with cat parasite 'twice as likely to explode in anger and suffer uncontrolled bouts of fury'

Link 'found' between parasite and psychiatric condition known as intermittent explosive disorder and aggression

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.People infected with a “harmless” cat parasite are twice as likely to explode in anger and suffer from uncontrolled bouts of fury such as road rage than uninfected individuals, a study has found.

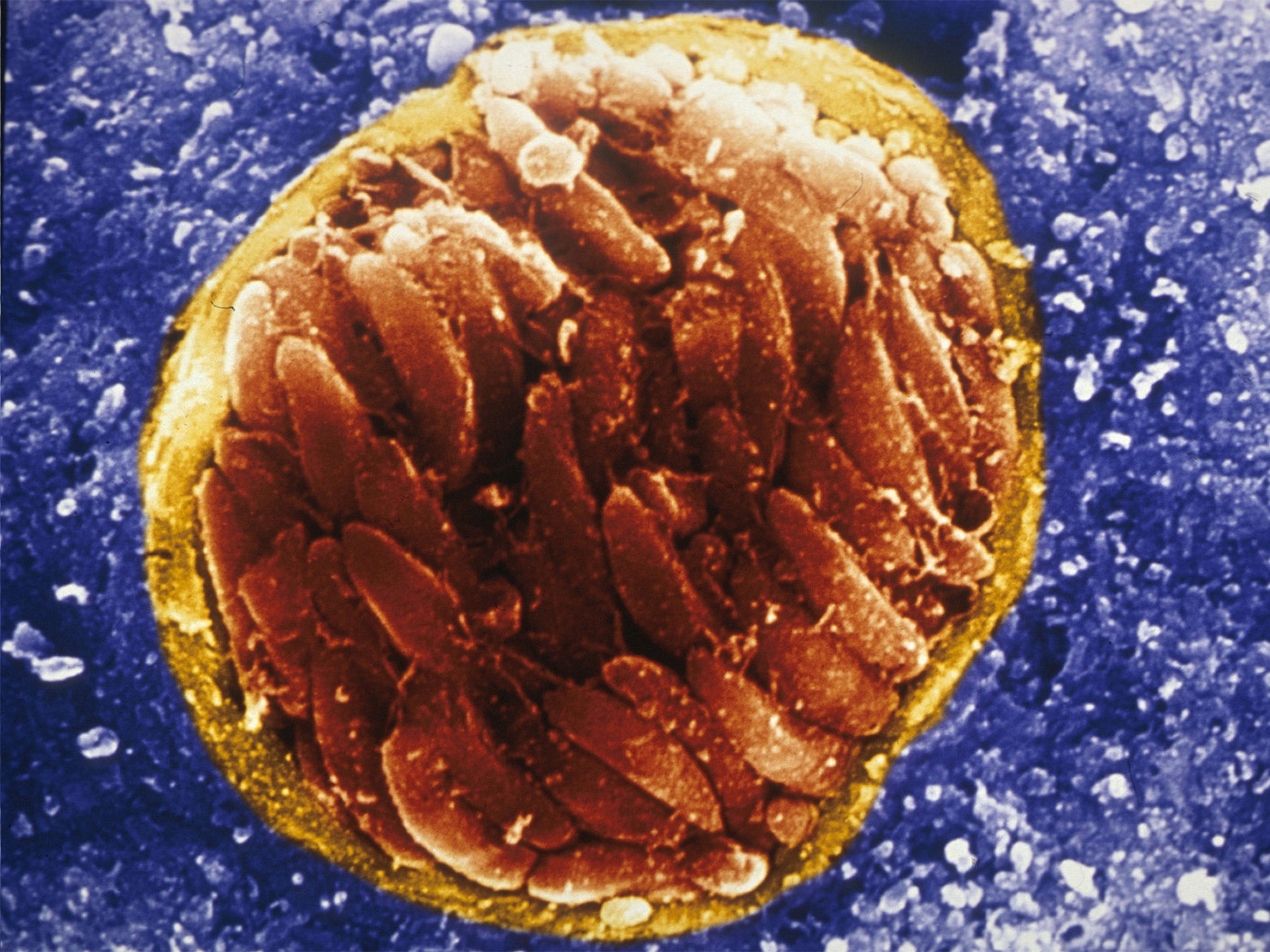

Scientists believe they have established a firm link between the relatively innocuous parasite, which can form cysts in the brain, and a psychiatric condition known as intermittent explosive disorder (IED) and aggression.

However, the link between toxoplasmosis and explosive anger is still weak and does not yet amount to scientific proof that the parasite, which can only complete its complicated life-cycle in cats, actually causes behavioural changes in humans, the researchers said.

The cat parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, is widespread in the environment, from soil to uncooked meat, and is estimated to infect about one in three people. Although many other animal species become infected, and T. gondii spores are ubiquitous in the soil, the parasite can only fully reproduce in cats, which excrete the parasite’s eggs when the felines first become infected as kittens.

A number of studies have indicated that toxoplasmosis can affect the behaviour of other animals, such as rodents, which become less fearful of cats, their main predator. A study earlier this year also found that toxoplasmosis changes the behaviour of chimps, making them less fearful of leopards, their natural predator.

Some studies have even suggested links to human behavioural disorders such as schizophrenia, although these findings have been questioned by other researchers.

The latest study involved a group of adults who had been diagnosed with intermittent explosive disorder. They suffered recurrent, impulsive and problematic outbursts of verbal or physical aggression, which was disproportionate to whatever situation triggered the behaviour – such as road rage.

Psychiatrists in the US estimate that some 16 million Americans suffer from intermittent explosive disorder, which is more than bipolar disorder and schizophrenia combined.

A third of the 358 volunteers involved in the study were classified as healthy “controls” with no behavioural problems. Another third had psychiatric issues, such as depression, but no intermittent explosive disorder, and the remaining third were diagnosed with the IED.

Blood tests found that 22 per cent of the people in the IED-diagnosed group tested positive for exposure to toxoplasmosis compared to 9 per cent in the healthy, unexposed group. Around 16 per cent of the psychiatric control group tested positive for toxoplasmosis, although they had the same levels of aggression and impulsivity as the unexposed, healthy group.

“Our work suggests that latent infection with the Toxoplasma gondii parasite may change brain chemistry in a fashion that increases the risk of aggressive behaviour," said Professor Emil Coccaro, of the University of Chicago, and senior co-author of the study published in the Journal Clinical Psychiatry.

"However, we do not know if this relationship is causal, and not everyone that tests positive for toxoplasmosis will have aggression issues,” Professor Coccaro said.

Across all the three groups in the study, those individuals who were positive for past exposure to toxoplasmosis scored significantly higher on psychiatric tests for aggression and anger. They also scored higher for impulse behaviour, although this became statistically non-significant when adjusted for aggression scores, the researchers found.

However, the study was too small and limited in scope to answer the question of whether toxoplasmosis infection actually changed the behaviour of people or whether the connection was due to some other, unknown factor, they said.

"Correlation is not causation, and this is definitely not a sign that people should get rid of their cats," said Royce Lee associate professor of psychiatry and behavioural neuroscience at the University of Chicago, and co-author of the study.

"We don't yet understand the mechanisms involved – it could be an increased inflammatory response, direct brain modulation by the parasite, or even reverse causation where aggressive individuals tend to have more cats or eat more undercooked meat. Our study signals the need for more research and more evidence in humans,” Professor Lee said.

The scientists said they will further examine the relationship between toxoplasmosis, aggression and IED to see if the cause-and-effect link can be established, or whether it is possible to treat behavioural problems by treating toxoplasmosis.

"It will take experimental studies to see if treating a latent toxoplasmosis infection with medication reduces aggressiveness. If we can learn more, it could provide [the] rationale to treat IED in toxoplasmosis-positive patients by first treating the latent infection,” Professor Coccaro said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments